Press release from University of Pretoria/Sea Search – Namibian Dolphin Project

Research led by scientists at the Namibian Dolphin Project has shed light on a new level of complexity communication amongst dolphins. This research, conducted by Morgan J. Martin, a PhD candidate from the University of Pretoria has found that the small Heaviside’s dolphins (Cephalorhynchus heavisidii) selectively switch between high frequency, echolocation clicks (i.e. biosonar) used to navigate and search for prey, and lower frequency clicks that comprise communication sounds which help to maintain their highly social lifestyle.

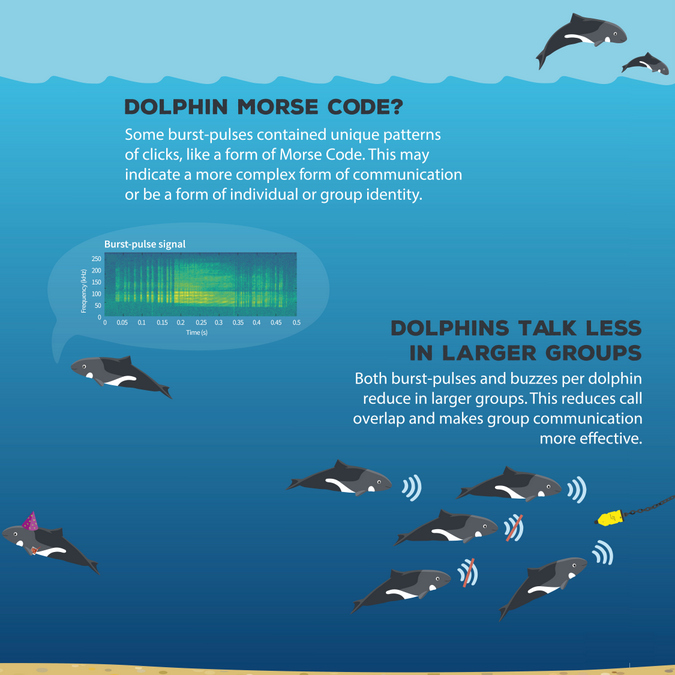

Further, unique patterns were found within some communication sounds which leads scientists to believe that these dolphins have developed a more sophisticated way to communicate messages or emotion. Also, Heaviside’s dolphins appear to decrease the number of sounds they produce when in larger groups, potentially as a means to control the noise level and improve communication across the group.

About Heaviside’s dolphins

Heaviside’s dolphins are only found in the Benguela Ecosystem along the west coast of southern Africa and range from southern Angola to the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa. They are found in shallow waters along the coast and are one of the smallest dolphin species on Earth (< 1.7 m long).

“Heaviside’s dolphins are a poorly understood species, and we are working to collect as much baseline information as possible on their numbers and behaviour,” says Dr Simon Elwen, a marine mammal expert at the University of Pretoria and director of the Namibian Dolphin Project.

What we know about sound use in Heaviside’s dolphins

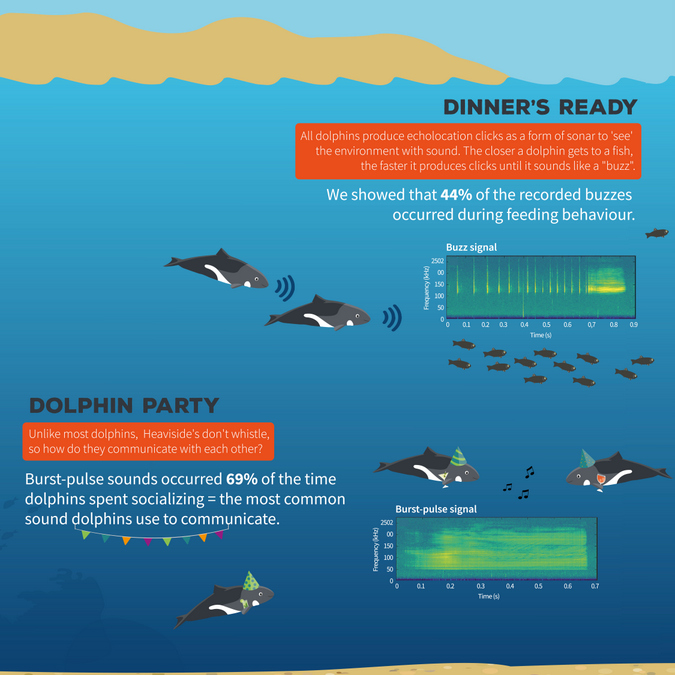

All dolphins use sound to find objects in their environment, such as fish. This process, called echolocation, involves the animal producing a sonar pulse, commonly termed a ‘click’, which hits a target, producing an echo which the animal hears and processes, effectively ‘seeing the world with sound’. Most dolphins echolocate with clicks which cover a range of frequencies, from around 10 kHz to 200 kHz; however, Heaviside’s dolphins are one of 13 species that have shifted their echolocation signals to occur only in an incredibly high and narrow frequency band around 130 kHz (almost seven times higher than the 20 kHz upper limit of human hearing).

Also, most dolphins also use other sounds, such as lower frequency whistles, to communicate over long distances; however, these 13 species do not produce whistles for communication. These acoustic adaptations are thought to reflect a type of acoustic crypsis, meaning that these adaptations decrease the dolphins’ risk of being overheard by predatory killer whales.

New findings

The current study links specific sounds produced underwater by Heaviside’s dolphins with their surface behaviours to understand the function of different sounds, including social signals.

“Although we can’t see what the dolphins are doing underwater, their surface behaviour is often used to interpret what is happening below the surface. By combining acoustic recordings of the dolphins underwater with the simultaneous behaviours observed at the surface, we can piece together a vocal repertoire of the types and functions of sounds these dolphins can produce,” says Dr Tess Gridley, a co-author on this study (based at the University of Cape Town).

This research has shown that the lower frequency sounds discovered are indeed used for communication, but Martin emphasises that there’s still much more to learn, “These dolphins communicate by emitting bursts of clicks very rapidly (more than 500 clicks per second) at highly varying repetition rates. We don’t yet know what information they can encode when they produce these sounds, but it appears they have a more complex communication system than previously understood.”

Imagine a potential form of dolphin Morse code where dolphins emit clicks in specific patterns or series, to communicate something specific like their emotional state. Unique patterns of communication sounds were paired with some particular dolphin behaviours seen at the surface including aerial leaping, backflipping, mating and tail slapping the water’s surface. So, they might be using this dolphin Morse code to tell group members what they are doing or that they are excited.

Also, the team investigated how the number of sounds produced by a group changes with increasing group sizes. Heaviside’s dolphins reduce the number of communication sounds produced when in large groups. This might be to keep them from ‘talking’ over each other and would help improve communication across the group.

This study has increased our understanding of the function of different Heaviside’s dolphin sounds as well as shed light on how this species mediates communication in groups.

Full report: Morgan J. Martin, Simon H. Elwen, Reshma Kassanjee, Tess Gridley (2019). To buzz or burst-pulse? The functional role of Heaviside’s dolphin, Cephalorhynchus heavisidii, rapidly pulsed signals. Animal Behaviour. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2019.01.007

The authors gratefully acknowledge research funding by the University of Pretoria, a United States Fulbright Research Fellowship, a National Geographic Society grant in conjunction with the Waiit Foundation, the Claude Leon Foundation and the National Research Foundation.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()