KINGSLEY HOLGATE'S AFRIKA ODYSSEY EXPEDITION

Our journey to Liuwa Plain from Matusadona National Park follows the Zambezi Valley via ‘Mosi-oa-Tunya’ (the smoke that thunders). To resupply, we push on via the elephants of Chobe and into Katima Mulilo in Namibia’s Caprivi Strip, which is bordered by the Linyanti, Chobe, Cuando and Zambezi Rivers. Crossing into Zambia and dodging convoys of Copperbelt trucks making their way to Walvis Bay, there’s still that exciting sense of leaving the southern Africa orbit behind: we love the easy-going nature of the Zambian people and the anticipation of what lies ahead. The anticipation on our journey to Liuwa Plain is pulpable. Sheelagh Antrobus shares news from the road.

Renowned African explorer Kingsley Holgate and his expedition team from the Kingsley Holgate Foundation recently set off on the Afrika Odyssey expedition – an 18-month journey through 12 African countries to connect 22 national parks managed by African Parks. The expedition’s journey of purpose is to raise awareness about conservation, highlight the importance of national parks and the work done by African Parks, and provide support to local communities. Follow the journey: see stories and more info from the Afrika Odyssey expedition here.

Singing across Sioma

We camp close to the base of the spectacular Sioma Ngonye Falls. Created by a basalt dyke that dams up the Zambezi, the falls form a broad crescent interrupted by rocky outcrops, creating a strikingly picturesque scene. Above Sioma Ngonye, stretching upstream towards Angola, is the vast Barotse floodplain and the river kingdom of the Lozi people. To get there in the old days was a great adventure of bad roads and ferry crossings, and you had to work at it. But now the old Senanga ferry that often broke down is no more, replaced by the new Sioma Bridge, which, if the wind is right, ‘sings’ as you cross it.

Barotseland is one of the most beautiful parts of the Zambezi and is well known for the Kuomboka Ceremony that has been taking place annually for over 300 years. That night, the wind blows cold; we huddle around the campfire as Ross knocks up his favourite chicken stew, and Kingsley, by the light of a headtorch, reads a note from an old expedition journal:

‘The Kuomboka is like something out of Cleopatra’s time on the Nile. When the annual flood waters arrive, the Barotse King… travels in his zebra-striped royal barge, the Nalikwanda, accompanied by 120 traditionally-dressed paddlers all rowing in perfect unison to the beat of the massive onboard royal drums and xylophones. Should a paddler, dressed in his finery of plumes and animal skins, miss a beat, he is unceremoniously tossed overboard amongst a flotilla of hundreds of dugout canoes and other boats, which escort the Royal Party to higher ground and the King’s palace at Limulunga, a short distance north of the bustling river port of Mongu.’

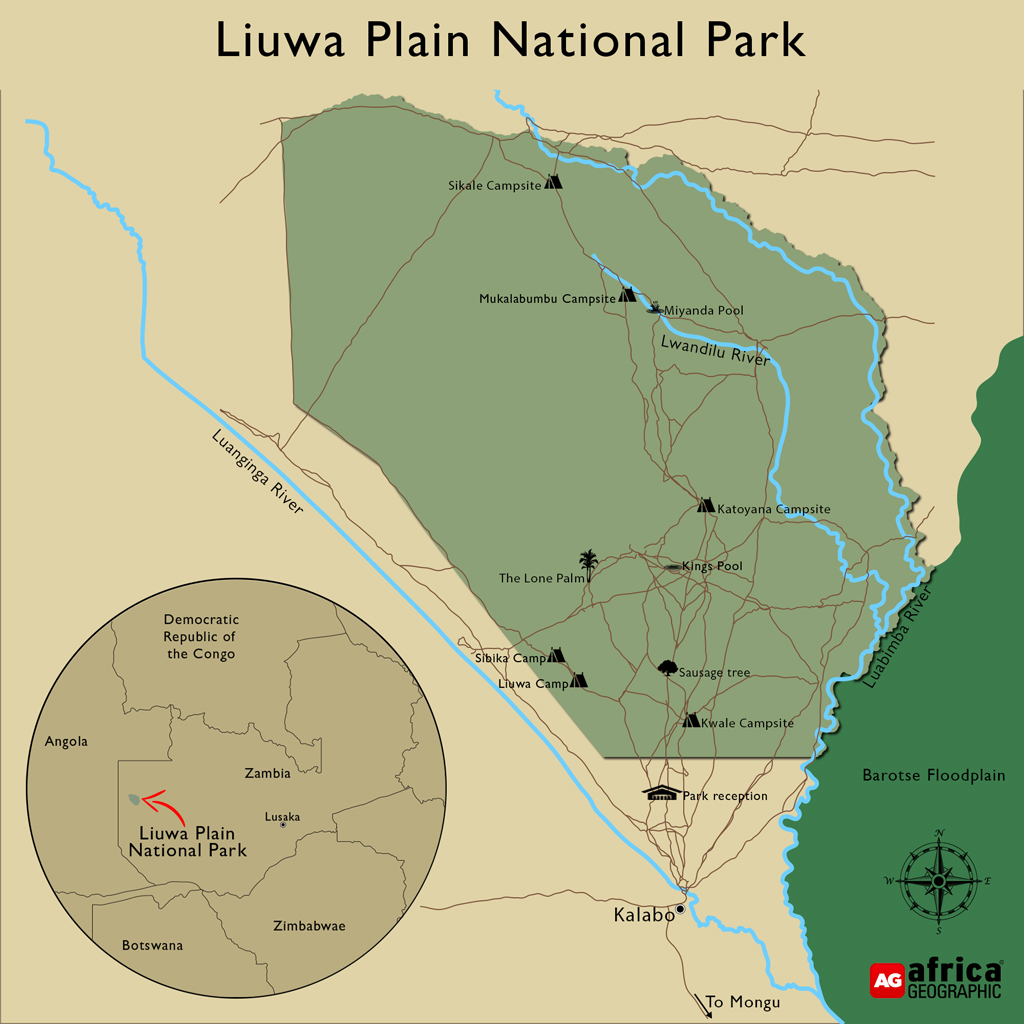

It’s no longer a long and challenging riverboat journey to cross the Barotse floodplains from Mongu; nowadays, there’s a raised 70km tarred road with a score of bridges that brings you to Kalabo – gateway to Liuwa Plain National Park, known for its spectacular gathering of blue wildebeest, the second largest wildebeest migration in Africa.

Far from the madding crowd

It’s at Kalabo that the tarred road ends. Smiling, good-natured Felix Mayungo, Liuwa Plain’s community development manager, will escort us across the Luanginga River by ferry. “Please deflate your tyres; from now on, we will be in deep sand,” he says. So, to the hiss of escaping air, curious locals cluster around the route map printed on the bonnet of one of our Defender 130s for a quick ‘expedition briefing’ on this odyssey to link all 22 African Parks-managed areas in 12 countries across the continent. With clanking and grating, the ferry noses up to the bank and drops the two ramps.

For the conservation-minded adventurer seeking to explore wild spaces far from the madding crowds, you should add Liuwa Plain National Park to your bucket list. Situated in western Zambia, these vast golden grasslands with 360-degree views, dotted with tree-islands, stretch between the Luanginga River to the west, the Luambimba River in the east, and of course, the Zambezi. With the arrival of the rains in December, the plains are transformed into a water wonderland of sparkling lagoons, vast herds of zebra, tsessebe, oribi, red lechwe, and, if you get your timing right, the second-largest migration of blue wildebeest in Africa.

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari lodges and campsites where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities? Plan and book your African Parks safari to Liuwa Plain and other parks here.

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari lodges and campsites where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities? Plan and book your African Parks safari to Liuwa Plain and other parks here.

Across the Luanginga, the Defenders come into their own with a throaty growl, as in high-lift sand mode, we tackle the soft, deep, winding tracks across endless yellow grass plains. It’s incredibly beautiful and has a wonderful sense of wilderness, space and freedom. We’re entering a whole new world, extending for some 3,660km²: and what a transformation since we were last here, more than 20 years ago.

The word Liuwa simply means ‘plain’. There’s a local legend that one Litunga (king) planted his walking stick on the plains, where it grew into a large Mutata tree, which can still be seen today. It is a magical paradise, especially when the wildebeest is massing on the plains and spring flowers carpet the white sand sea.

In 1890, the King of Barotseland appointed his people as custodians of this landscape. But, by the turn of this century, decades of unsustainable land use and poaching – especially during the 1975-2002 civil war in neighbouring Angola when soldiers poured into the park in pursuit of meat and money – caused a rapid decline in all species and reduced the lion population to just one lonely lioness.

The Liuwa Plain legacy

In 2003, realising what was at stake, the Barotse Royal Establishment and Zambia’s Department of National Parks and Wildlife invited African Parks to help restore the legacy of Liuwa Plain, and with this came hope. Effective conservation law enforcement strategies were implemented to reduce bushmeat poaching, and sustainable land use and fish harvesting methods were introduced to the communities. Then, in 2008, a series of wildlife reintroductions were rolled out to restore species that once roamed the plains in abundance. First came lions, eland and buffalo to provide a healthy prey base for the growing predator populations. Today, the park is home to 47,000 wildebeest and thousands more antelope, large hyena clans, a thriving cheetah population, wild dogs and lions, and is a sanctuary for over 300 bird species.

One expedition Defender behind the other, we follow meandering, deep sand tracks across the pancake-flat terrain. The scale is bewildering; the cloudless sky looms above like a massive dome as the horizon disappears over the Earth’s curvature. The sense of space, silence and freedom is blissful. We stop at the much-revered King’s Pool, where, by tradition, a percentage of fish caught here by the Liuwa Plain communities is given in tribute to the King of Barotseland. Catfish bubble and burp, saddlebill storks and wattled cranes take to the sky, African jacana scuttles across the water lilies, and a secretary bird stalks off into the distance.

Felix slips off his shoes and wades in to add a splash of symbolic water to the expedition’s calabash – a ceremony taking place at 22 special locations on this journey to link all African Parks-managed areas across the continent. Heading back to camp as the sun disappears in a fiery red ball, we’re thrilled to see the wild dog pack setting out on a hunt.

“One of the beauties and unique qualities of Liuwa is the coexistence of people and wildlife,” Hickey Kalolekesha, the park’s Field Operations Manager, tells us. “All the chiefdoms have radio comms with us and keep us informed of wildlife movements and suspicious individuals entering the area. And the people say: ‘These are OUR wildebeest, OUR Lion.’…there’s an entrenched sense of ownership, and we all work together – community, government, traditional leaders – to protect this special place. The Liuwa landscape gets under your skin: the openness, the unusual sightings, the tranquillity and the happy people here – you can’t fake the Liuwa Smile,” he says with a big grin of his own.

The park is now the largest employer in the region and provides critical education and health benefits to hundreds of community members. And there’s excellent work being done to help generate income from natural resources: beekeeping, honey processing, dried mango production and a busy fish-drying facility that even exports to the Congo. Over 200 children have received scholarships; more than 4,000 local farmers have benefitted from skills training. Because of the reintroduction of wild dogs, the park has also initiated a rabies-vaccination programme, and thousands of community dogs and cats are now safe from this deadly disease.

What’s also great for the overland adventurer are the opportunities to pitch your tent and throw out your bedroll at several community-owned wild campsites dotted across the plains, which generate tourism income for the Liuwa people.

In the shade of a 100-year-old mango tree, to the vibrant sounds of kids practising their poetry, singing and dancing for the annual Liuwa Drama Festival in which every community school competes (this year’s theme is ‘Against Wildfires’), we meet Area Chief Mundandwe. “Conservation isn’t new to us – it’s been part of our way of life for time immemorial,” the chief begins before telling us the poignant story of Lady Liuwa – the last lioness who’d lost her pride to hunters and poaching. “She was such a friendly lioness but so lonely that she would seek out human company. One of her favourite places was the thicket of trees where Mambeti, the daughter of a Lozi chief, was buried near the King’s Pool. There used to be many lions here: I remember as a child not being able to go to school sometimes because they were close by. So we, the community, were delighted when African Parks suggested reintroducing them. Lady Liuwa finally had a family again, and though she couldn’t breed, she helped raise a new generation of Liuwa Plain lions. She died of old age in 2017, and in our culture, we believe she was the spirit of Mambeti.”

“My hope is that African Parks remains here for a very long time and there’s lots of goodwill to also incorporate the Game Management Area to the north-west of Liuwa, to give the wildebeest full protection on their migration,” says Chief Mundandwe before bidding us farewell. In the expedition’s Scroll, he writes: ‘All creatures were created for a purpose, and we are all inter-connected. Conservation is doing God’s work; it takes sacrifice but it’s our job to protect them.’

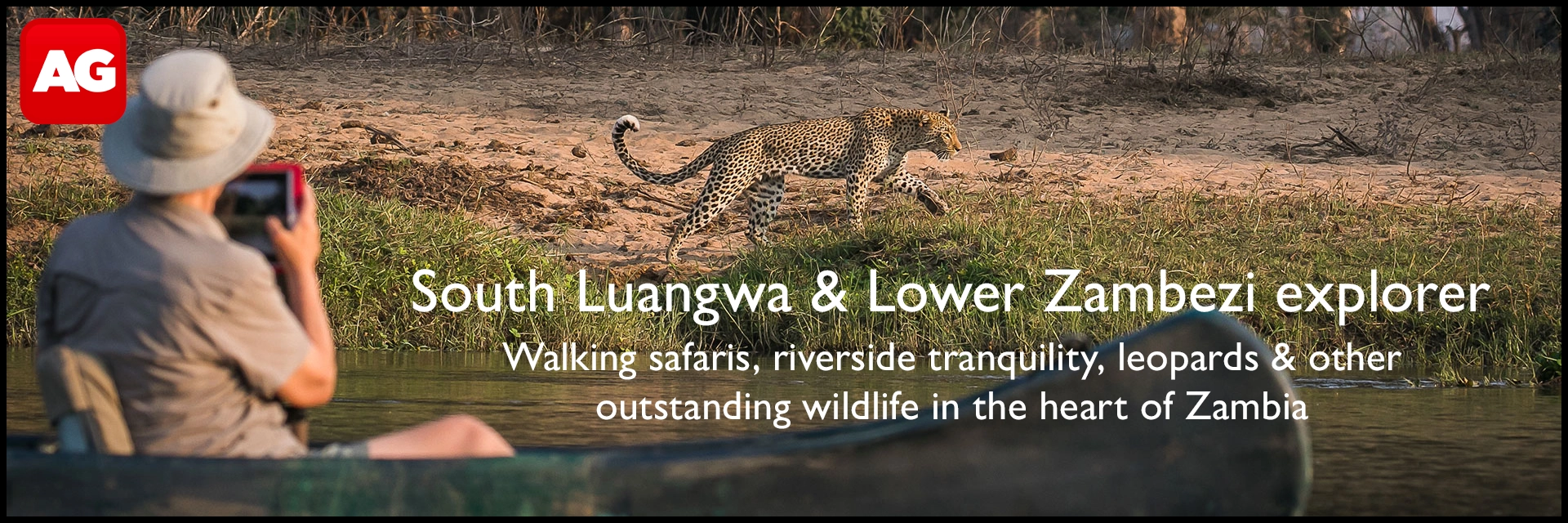

Considering Zambia for your next African safari? Read more about a safari in Zambia here, or check out our ready-made safaris here.

Considering Zambia for your next African safari? Read more about a safari in Zambia here, or check out our ready-made safaris here.

Onward, Liuwa Plain

We loved our time at Liuwa: busy days working with the smiling communities, the generosity of spirit of the committed African Parks teams and the sense of endless space and solitude. Then comes a surprise gift: our final night is hosted by eclectic King Lewanika Lodge, named after the Litunga: hot showers, fluffy towels, warm blankets, and food not cooked over a smoky campfire! What a treat – made even more memorable as Godfrey and Elias, the lodge’s charismatic guides, at last light locate 10 of the park’s 17 lions engaging in a beautiful reunion of head-rubbing, tail-waving, purring delight. That night, the staff dressed in traditional costumes gave us a cultural enactment of music and dance from the 300-year-old Kuomboka ceremony.

‘What makes Liuwa so special is the equal respect given to the communities and wildlife alike,’ writes researcher Sarah Weiner in the expedition’s Scroll. ‘We are all one and the same, coexisting in this beautiful landscape. There is magic in the silence and the whispering wind; magic in the breathtaking sunrises that greet us in the mornings and the sunsets that put us to sleep each night.’

This Afrika Odyssey journey is about finding stories of hope for Africa’s wildlife and wild spaces. Our time at Liuwa Plain – so different, so full of conservation, community and culture – is no exception.

Back across the Luanginga ferry, we turn the Defenders towards the expedition’s next destination. It’s said to be the second largest park in the world, about the size of Wales, and it’s had a complicated past; I will keep you posted.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()