Waters and sky, shoebills and lechwes

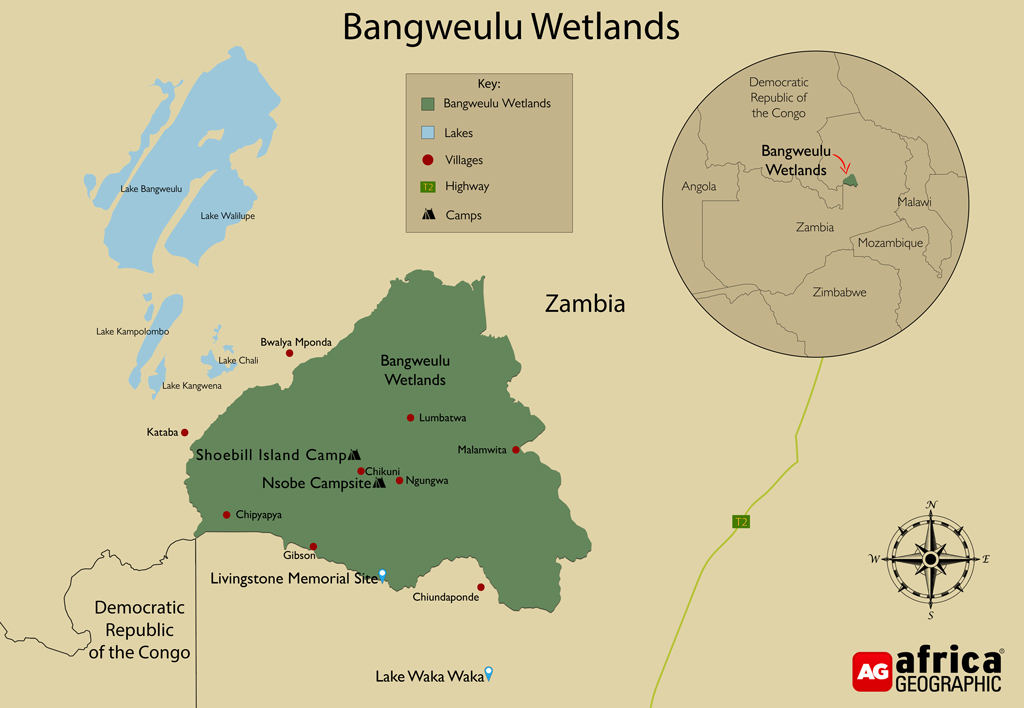

It’s early in the morning, long before sunrise. My bed is cosy and warm. The morning air outside is cold. Our tent on Shoebill Island, a tiny islet in Bangweulu Wetlands, Zambia, is nestled in a grove of quinine trees (Rauvolfia caffra), and I’m reluctant to leave it and go out into the cold. We’re awake early because we plan to paddle through the narrow, reed-lined channels from camp to the floodplains to see the endemic black lechwes that call this unique wetland home. Bangweulu means ‘where the water meets the sky’, which perfectly describes this extraordinary wetland in northeastern Zambia.

We reach the floodplains just as the sun peeks over the horizon. The sky turns from grey to a delicate shade of pink. We stand shivering on the causeway that runs through the floodplains, surrounded by thousands of black lechwe, barely visible in the thick morning mist. Having spent the night in the shallow water for safety, the lechwe, hindquarters characteristically higher than their shoulders and elongated, splayed hooves preventing them from sinking into the swampy ground, are now slowly splashing their way back towards the tree line, grazing as they go.

Black lechwe are listed as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List, and their numbers have declined drastically. Numbering more than 250,000 in the 1930s, by the 1970s their numbers had plummeted to around 16,000. Fortunately, in 2008, conservation NGO African Parks began working in these wetlands, when they signed a long-term agreement with Zambia’s Department of National Parks and Wildlife (DNPW) and Community Resource Boards in the area. Tigether, they committed to sustainably managing the wetlands to benefit wildlife and people. Since then, black lechwe numbers have slowly but steadily increased, currently standing at over 42,000 (though still classified as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List).

Find out about Zambia for your next African safari. We have ready-made safaris to choose from, or ask us to build one just for you.

Find out about Zambia for your next African safari. We have ready-made safaris to choose from, or ask us to build one just for you.

I’ve travelled here with a long-time friend and professional wildlife photographer, Patrick Bentley, who was assigned to photograph the swamps and their inhabitants. Patrick is also the reason we are up before sunrise. As we will learn on this trip, lighting and timing are everything to a photographer, and if that means getting up before dawn because that’s the best time to photograph something, then that’s when we’ll be getting up! We spend several hours watching and photographing the lechwe, but once the sky is light and they’ve all but disappeared, it’s time to paddle the 40-minute canoe trip back to camp and breakfast.

The Bangweulu swamps spread across 6,000km² and consist of an extraordinary, community-owned protected wetland with a rich and diverse ecosystem of floodplains, seasonally flooded grasslands, miombo woodlands and permanent swamps, making it one of Africa’s most important wetlands. The area floods during the wet season (November–March), and it receives an average annual rainfall of about 1200mls. The resultant effect is that the water line advances and retreats by as much as 45km. The flood waters’ seasonal rise and fall dictate life in the swamps.

Bangweulu comprises around 60,000 local villagers who migrate seasonally with water levels and depend on the marshlands to sustain their traditional way of life. They are permitted to live here seasonally and to harvest natural resources sustainably. However, this sustainable approach has not always been the case. Relentless poaching exterminated most of the area’s large mammal species, decimated the black lechwe population and left only a handful of buffalos, elephants and tsessebes. Overpopulation, overfishing, and unsustainable pressure on wildlife ultimately led the local Community Resource Boards and the Zambian DNPW to enter into the long-term agreement with African Parks to manage and protect the area sustainably.

Aside from black lechwe, we are also out to see the wetland’s two other flagship species during our sojourn here: the rare and critically endangered shoebill and the vulnerable wattled cranes. Bangweulu Wetlands is home to an abundance of birds; over 680 species are found here, and paddling back to camp, we see many of them! We see kingfishers (malachite, pygmy and pied), ibis (sacred and glossy), geese (spurwing and Egyptian), bee-eaters (blue-cheeked and blue-breasted), black-winged terns, grey-headed gulls, Hottentot teals, woolly necked storks, African golden weavers, whistling ducks, egrets, herons, bitterns and more. The jewel in Bangweulu’s ornithological crown, though, is the shoebill.

Shoebills are endangered. The IUCN estimates the global population of these incredible birds to be between 3,300 and 5,300, and their numbers are decreasing. Shoebills are classified as vulnerable, and people worldwide come to Bangweulu to glimpse these tall, blue-grey birds with their shaggy crests and piercing yellow eyes.

Shoebills are in a family of their own (Balaenicipitidae). Once classified as storks, shoebills are now considered closer to pelicans (from anatomical comparisons) or herons (from biochemical evidence). However, they share some traits with storks and herons, like long necks and the characteristic legs of wading birds; their closest living relatives are pelicans and hamerkops. The prehistoric-looking shoebills are threatened by the illegal live-bird trade – particularly through the sale of chicks as pets, for which the demand seems to be increasing.

For birdwatchers, shoebills are one of the most sought-after birds in Africa. Here in the wetlands, local communities recognise the tourism value of shoebills and the economic benefits they bring. Community members guard nests, ensure chicks can fledge, and generally keep a watchful eye on the birds. The protected area within Bangweulu Wetlands is currently home to between 300–500 of these birds, and seeing one was our plan for the afternoon.

Bangweulu Wetlands is a successful example of community-driven conservation, the ultimate goal being to ensure both people and wildlife will benefit equally from the area’s incredible natural resources. When African Parks began working here, overpopulation became a colossal problem. With approximately 60,000 people living legally within its boundaries and 100,000 more living in the surrounding areas, poaching, overfishing, cutting of trees, and limited educational opportunities meant the future looked bleak. The entry of African Parks saw the implementation of wildlife education, reproductive health programmes and beekeeping programmes.

African Parks also developed the Shoebill Nest Protection Programme in 2012, to ensure the protection of Bangweulu’s shoebills. Community members are employed as guardians to protect the shoebills round the clock during peak nesting season (June–November). In May 2022, the Shoebill Captive Rearing and Rehabilitation Facility was established, a facility designed to rear chicks in captivity and increase breeding success. The facility is the first of its kind in the world, with state-of-the-art incubators and brooders to care for shoebill chicks at every stage of their development, with all chicks to be released back into the wild.

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari lodges and campsites where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities? You can plan and book your African Parks safari to Bangweulu Wetlands and other parks by clicking here.

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari lodges and campsites where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities? You can plan and book your African Parks safari to Bangweulu Wetlands and other parks by clicking here.

The employment of over 100 rangers, who patrol, remove snares and confiscate illegally caught fish and poached game meat, has also positively impacted conservation. African Parks have also successfully translocated many animals into Bangweulu, including zebra, impala and buffalo. Tourism has been another focus, with two community camps being opened, as well as the fabulous Shoebill Island Camp, where we stayed.

For our first shoebill sighting, we searched for a rescued, habituated shoebill we’d heard about. As a chick, the shoebill had been removed from its nest in the swamps. The poachers were actively trying to sell the chick when they were apprehended. The chick was confiscated and returned to the wetlands, where rangers nurtured it until it was ready to return to the wild. Having become somewhat used to humans, he is now often easy to find in the vicinity of a local fishing village. Heading to where the rescued chick had last been seen, our guide stands at the front of the canoe, long pole in hand, propelling us through the narrow channels between the thick reeds and papyrus.

Many people live seasonally in the swamps, and we pass several small mud and thatch-hut settlements. Music blares, children laugh and play, men talk, and women do ‘chores’ around their temporary dwellings surrounded by water. Our guide calls to a man on the bank, and he shouts back. Before we know it, he’s jumped aboard our canoe. Taking the guide’s pole, he steers us towards where he’d seen the shoebill that morning.

Then we see it – lying on top of an ant hill on the outskirts of a fishing settlement. Anchoring our canoe at the edge of the channel, we remove our shoes and clamber overboard. Wading through knee-deep water, we get a bit closer, and the shoebill casts his enormous eyes on us, seemingly unperturbed. We don’t get too close, though we could have if we’d wanted to. Seeing us, the shoebill, in a fit of exhibitionism, stands up, preens a little, flaps his wings experimentally, and displays some fancy footwork before lying down again and appearing to fall fast asleep. We splash back to the canoe and head back to camp, stopping en route to drop off our new ‘guide’. In the coming days, we will see several more shoebills and get just as close to some, but the sight of my first shoebill will always be a wonderful memory.

As we return to camp, the sun sinks in the sky. Hundreds of glossy ibis, silhouetted like necklaces against the sunset, fly out of the swamps to roost for the night. Great white and pink-backed pelicans circle overhead, and a hippo surfaces to voice his irritation as we pass through his territory. We reach camp just after dark and sit by the fire. Millions of stars sparkle overhead, and countless fireflies flit in the shadows outside the circle of firelight, glimmering like fallen stars. We hear music and chatter from a fishing village across the water, and a hyena calls in the distance.

The following day, we’re off to look for shoebills again. Anticipating a long day of paddling and scrambling through reeds and undergrowth, we’ve packed lunch. We needn’t have bothered. Barely 20 minutes from camp, we find our first shoebill of the day. A little older than yesterday’s but equally undisturbed by our presence, he stands and watches us, looking like a child who’s raided the dress-up box and chosen an outfit of old-fashioned pantaloons and coat. With his large, splotchy, sharp-edged bill, he forages in a channel opened by local fishermen, ready to decapitate or skewer any fish, frog or reptile he sees. A teenage boy arrives to repair some fishing nets that have been damaged by a hippo overnight. The shoebill stands watching the boy, too. Only once the boy has finished repairs and starts walking a little closer does the shoebill, with a mighty leap and a few heavy wing beats, take to the air and fly away.

It’s only 8am, and as we’d planned a much longer day out, we carry on paddling. After a few more bends, we find several wattled cranes and settle down to watch them.

Wattled cranes are the sole inhabitants of the genus Bugeranus. This is the rarest of Africa’s crane species, and its numbers are in decline, primarily due to the disappearance of wetlands. The future of wattled cranes in Africa may well depend on Zambia. The country is home to more than half the world’s wattled cranes, with Bangweulu holding 10% of the global population of these incredible birds. Classified as vulnerable, there are only an estimated 7,700 individuals worldwide. Even in Zambia, the continent’s stronghold, wattled crane numbers only stand at 4,000-4,500.

The apparent reason for the scarcity of wattled cranes is the disappearance of wetlands. Still, other factors contribute to the decline of the second-tallest flying bird in the world. Wattled cranes are highly territorial during breeding season, defending an area of approximately 1km², meaning breeding densities are relatively low. In addition, wattled cranes have the lowest recorded ‘recruitment rate’ of any wild crane species (successfully raising young to the stage of joining the adult population). Only around 13% of breeding pairs will successfully fledge a young bird, which is particularly worrying given that paired birds generally only lay one egg per breeding attempt, and their breeding cycle is highly irregular. The future looks a little bleak for these birds, though this was easy to forget as we saw pair after pair of the long-legged, bare-faced, black-capped birds, with their distinctive long white necks and white wattles dangling at their throats.

Having had such early success with our shoebill search and exhausting the wattled crane watching, we take our lunch back to camp. On our way back, we locate yet more shoebills. The first uses its long legs and toes to traverse the sodden marsh. We don’t fancy negotiating the wet, floating islands of vegetation, so paddle on. Children playing nearby shout to get our attention, pointing out yet another shoebill. We paddle closer. This one stands patiently as we photograph him, looking left and right as if trying to decide his most photogenic side. Eating lunch back at camp, we see yet another shoebill, this time soaring high overhead, its long legs and distinctive large bill silhouetted against the bright sky.

Visiting Bangweulu and all its special creatures is the best way to support the conservation and long-term sustainability of this truly special water wonderland. It is, without a doubt, a place worth conserving and visiting.

Resources

Read about and book your Bangweulu visit here.

Read more about Bangweulu Wetlands here.

Read about Kingsley Holgate’s expedition to Bangweulu Wetlands, as part of a journey of hope across Africa.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()