Bee wise

![]()

On the south-western tip of Africa, a bee-conservation group has spent the last seven years discovering the wisdom of our wild honeybees.

I make it to Simon’s Town to meet Ujubee’s Jenny Cullinan and Karin Sternberg just before the Covid-19 lockdown is enforced in South Africa. The national parks are already closed and the wildlife in Cape Point, Ujubee’s primary research area, has the place all to itself and is probably giving a big sigh of relief.

As bottles of sanitiser fly off the shelves faster than they can be reordered and customers are sanitising hands as they enter and leave shops, the Ujubee pair tells me that wild honeybees have a similar cleanliness procedure which ensures the health of the colony. I have never thought of bees as having a similar lifestyle or behaviour pattern to human beings, but I am soon to learn otherwise. These small social creatures have been around for about 80 million years and apparently have quite a lot to teach us.

Jenny explains that because wild honeybees live in such close proximity to each other, hygiene is of utmost importance as viruses and bacteria are their biggest threat. “The foraging bees that exit the nest to engage with the outside world disinfect themselves regularly,” she says. The key is in the propolis, the dark resinous substance that often acts as an enclosing entrance wall in a wild honeybee nest. “The bees maintain the essential oils in the propolis, continually bringing back resins to add to it.” These antibacterial and antifungal essential oils are applied whenever they leave the nest or on their return when they can be seen wiping themselves down.

The wild Cape honeybee, Apis mellifera capensis, immediately has my attention. And as the dogs curl up in their baskets and the first of the winter rains shower down peacefully outside, I listen to Jenny and Karin’s fascinating story. Before they teamed up in 2013 and went for their first walk in SanParks’ Cape Point Nature Reserve, there was little information about wild honeybees. Although there was a lot of material about apiarists’ box-hives, the information about bees in the wild was virtually non-existent. When Karin did some research, the only information she could find was from a scientist by the name of Anderson done in the 1980s when Cape Point was being proclaimed as a sanctuary. “He maintained that there were very few colonies in Cape Point. He thought that there was possibly a maximum of five colonies of wild honeybees,” she tells me. “Seven years down the road we have found 94 nests, about 83 occupied. Back then, we had to start from scratch.”

At the time Jenny, who had moved to Cape Town from Kwazulu-Natal, was eager to meet up with the Cape wild honeybee, a different subspecies to the wild honeybee, Apis mellifera scutellata, that she was accustomed to further north in the summer rainfall areas. She had grown up on a farm, respecting the wild bee colonies that had made their home in the shed, in an old drum outside and under the bath. “I remember the honey-waxy smell when I bathed,” she says, reminiscing about the comforting fragrance that is happily intertwined with her childhood memories. Her father kept several beehives, and when Jenny arrived in the Cape and started to learn about wild honeybees, she soon realised that she had to quickly discard all that she had learned as a beekeeper. She discovered that honeybees live a completely different life in the wild than when managed in hives. The team started to collect data from hours of observation in the field, learning to record it scientifically with the assistance of entomologist Geoff Tribe. Their findings would intrigue conservationists worldwide. And, as South Africa, thankfully, still has a healthy wild honeybee population, Ujubee (Uju meaning ‘honey’ in Zulu) focuses on collaborating with and giving presentations to conservation bodies around South Africa, increasing the resource of knowledge about our wild honeybees, an important part of our indigenous wildlife.

Karin and Jenny, under the umbrella of the self-funded Ujubee project, have been absorbed for the last seven years locating the wild honeybee nests that are found in hollows, crevices and under boulders in the reserve and learning about the resident colonies, as well as the many solitary bees that reside in the area. Not using any protective gear, they get up close and personal with the bees, so it’s vital to tune into the bees’ world and to learn how they communicate and live. Several years ago when I first heard them give a talk about how the wild honeybee colonies survive the fires that sweep through Cape Point, I was amazed at the photos of them lying on the ground right next to a nest, a far cry from the heavy protective gear I had always associated with working with bees in boxes.

“Because we’re unprotected in front of the bees, and we’re up close, the senses are heightened in the presence of a colony. You smell everything more intensely, you look more intensely at the behaviour, you listen so intensely,” Karin explains, transporting me to the place of their fieldwork on the often-windy Cape peninsula. Jenny adds, “Their language is so different to ours; it’s in vibrations, and it’s in chemicals, and it’s in dances – that’s how they communicate. We have to translate the bee language through ourselves into the human language – so humans can understand the bee world.”

Karin and Jenny have discovered on their journey of becoming wild-honeybee behaviour specialists that the bees co-exist harmoniously with other species. “By watching honeybees, it has opened the world to everything else around the colony,” Karin says. “Because you become a part of their world, you also look at how other species are interacting with the bees.”

They explain that although people think of bees as pollinators, they’re actually an essential part of the food web. What’s really interesting is that beekeepers always try and get rid of ants, wax moths and larvae, hive beetles etc., but in nature, they co-exist because they each have a function in the nest.

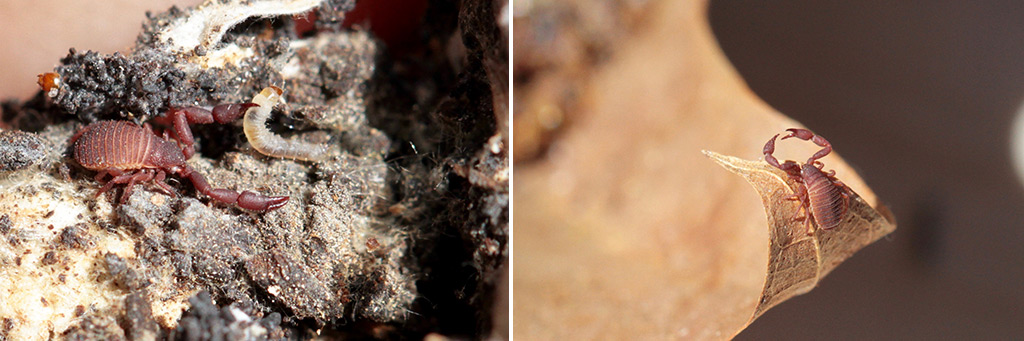

For example, I learn that the tiny pseudoscorpions – with their hairy pincers that enable them to pick up vibrations – sit on flowers and wait for the bees, catching rides on their legs to the different nests. There the bees feed the extraneous wax-moth eggs to them, thus managing the number of eggs that are allowed to hatch in the nest. The bees even ensure this happens in an organised manner by bringing the eggs out onto a feeding station and dropping them there for them to eat. The wax moths’ role in the nest is to eat the wax when it is damaged and old, cleaning out the nest so the bees can rebuild it, so each species benefits the other. The wax moth larvae eat the leaf litter, which collects under the colony, doing their bit to help maintain the environment and hygiene of the colony. Lizards play their part by eating the dead bees that are deposited outside the nest. All the various species survive the fires that routinely rage through the peninsula because they live with the bees.

The Ujubee women tell me how they are absorbed by this small, multi-layered and complexed world and the many interactions between the species. Jenny laughs, “When we come home, we watch ‘bee’ movies, quietly focusing on what’s going on between the species. They all need each other, and they all realise that – and function well together. And that’s something that our species needs to understand, that there’s strength in diversity.”

The discoveries that Ujubee has uncovered in their studies are mesmerising. The project has extended its range over the last few years, with research also being done in Scarborough, Noordhoek, on organic farms in the Klein Karoo, the area around Porterville (which has very few wild colonies left) and it is moving further afield into Limpopo to use the information it has gleaned over the years to aid conservation efforts. Their helpful team of Ujubee volunteers in the different areas provides valuable assistance with data collection and understanding bees in different biomes.

Ujubee realises that an important part of their work is raising awareness about the wild honeybee and making the knowledge available for conservation purposes. The presentations they offer are intriguing, with their excellent photographs and the incredible footage of bee dynamics, as is the information about the synergy in the wild honeybee colonies – and dare I say – the intelligence of the bees.

Wild honeybees seem to be one up from us on quite a few other things as well. Karin and Jenny explain how they are always in sync with the natural environment, regulating the number of eggs they lay according to the plants that are flowering at that time. “They take all things into consideration before a new colony is created. This includes all the other pollinators – butterflies, bees, birds, rodents, moths – the food availability and the nest site availability. The solitary bees, like the honeybees, invest in the home they make for their young. They are future thinkers – they invest in their children.”

When I hear about life in the wild honeybee colony, I can’t help thinking that If these small creatures are aware of all this, can you imagine what we human beings can accomplish.

Jenny sums up her years of experience with these small creatures that have changed her life immensely. “The wisdom that they have about living on this planet has profoundly influenced who I am and how I move around. It has changed an enormous number of things in my life, and I’m truly grateful to be around a species that’s much older than us and which understands what it means to live in the community of life. An evolved species that lives healthily on Earth, it has learnt to fit in with everyone else. And doesn’t damage or destroy. It has taken millions and millions of years of refinement to understand that you don’t live on this planet by taking too much or by taking more than what you need.”

Although I could stay and listen to them talk about the bees for hours, the light is dimming outside, the dog is asking for its supper, and there are arrangements to be made for the pending lockdown. As I drive off, looking down onto the Simon’s Town harbour below, I think of what they said in terms of what Covid-19 has to teach us, from what they have learned from the wild honeybees. “We have to go back to first principles. We have to go back to what we have done, what we are doing and look at how we can do it differently.”

And many of the answers we can find by looking at this ancient species and gleaning the wisdom garnered over the centuries.

Photos by Ujubee and supplied (Geoff Tribe & Fiona Anderson)![]()

About the author

Freelance writer, Ron Swilling’s work is regularly featured in travel and outdoor magazines in South Africa and Namibia. Her work has also appeared in books Wild Horses in the Namib Desert: An equine biography, Road Tripping Namibia and the children’s story The World Famous Sunbeam Collector. Ron’s travels lead her off the beaten-track to discover diamonds in the dust, wild desert horses, unspoiled nature and freedom in never-ending landscapes. When at home in Scarborough, Cape Town, she delights in finding wonders in her very own back garden, like the Cape’s wild honeybees.

Freelance writer, Ron Swilling’s work is regularly featured in travel and outdoor magazines in South Africa and Namibia. Her work has also appeared in books Wild Horses in the Namib Desert: An equine biography, Road Tripping Namibia and the children’s story The World Famous Sunbeam Collector. Ron’s travels lead her off the beaten-track to discover diamonds in the dust, wild desert horses, unspoiled nature and freedom in never-ending landscapes. When at home in Scarborough, Cape Town, she delights in finding wonders in her very own back garden, like the Cape’s wild honeybees.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()