KINGSLEY HOLGATE'S AFRIKA ODYSSEY EXPEDITION

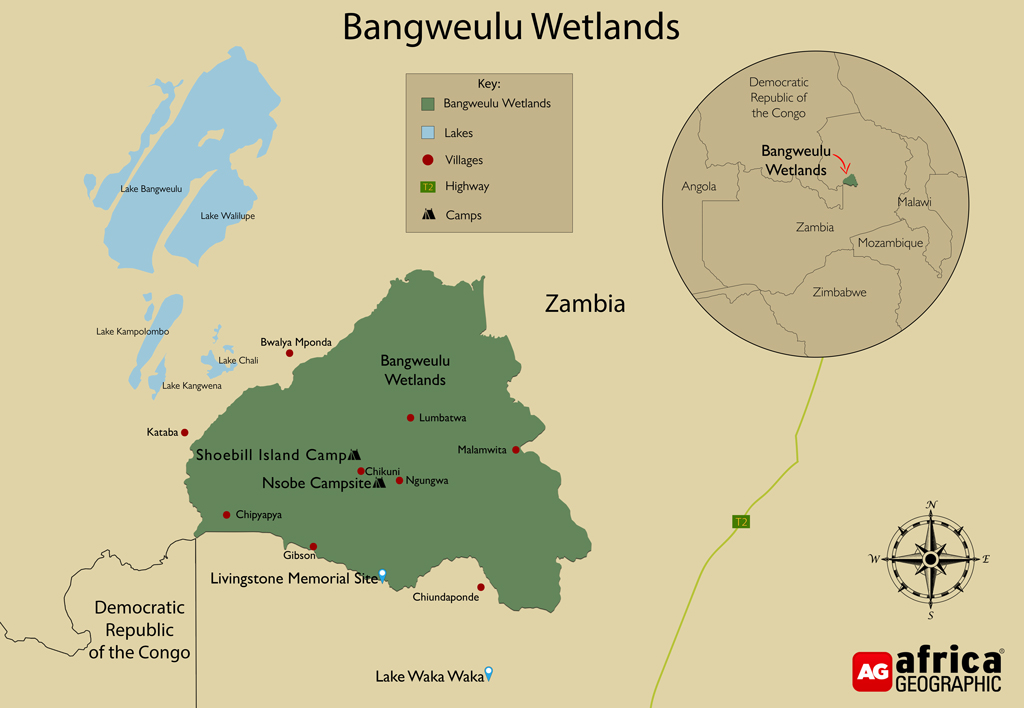

Behind us are Iona in Angola, Matusadona in Zimbabwe, and Liuwa Plain and Kafue national parks in Zambia, all of which have shared incredible stories of hope for Africa’s conservation and communities. It’s mid-afternoon by the time we swing onto the road that leads towards the Bangweulu Wetlands in north-eastern Zambia and down a narrow sand track lined with mud-and-thatch homesteads, cassava and maize fields, droves of cheerful, waving kids, heavily laden bicycles and roadrunner chickens.

Then, across rickety plank bridges and through swathes of elephant grass taller than the Defenders, in a race against the setting sun to reach a small, secretive lake called Waka Waka, hidden in the miombo woodlands.

Renowned African explorer Kingsley Holgate and his expedition team from the Kingsley Holgate Foundation recently set off on the Afrika Odyssey expedition – an 18-month journey through 12 African countries to connect 22 national parks managed by African Parks. The expedition’s journey of purpose is to raise awareness about conservation, highlight the importance of national parks and the work done by African Parks, and provide support to local communities. Follow the journey: see stories and more info from the Afrika Odyssey expedition here.

Of bicycles and dugouts in Bangweulu

It is not our first time here. Around the campfire, we reminisce about a memory-lane expedition that some 20 years ago had taken us along this same route. With nyama sizzling on the coals and enamel mugs of sustenance, Ross reminds us of how, in those early days, we’d taken our battered old Landy 300 Tdi’s as far as possible into the swamps. The rains had just ended, and it was tough going, the wheels of the overloaded Landies spinning as we pushed, slid and winched through black mud to reach the vast open plains of Bangweulu. And then, in dugout canoes, on old ‘Made in India’ bicycles, and wading through the swamps on foot with a team of porters supplied by Chief Chiundaponde, we’d travelled through the constantly shifting channels and sandbanks.

That night in our tent on the shores of Lake Waka Waka, listening to the sound of the wind sighing in the trees, I think back to how we’d camped at Chikuni Island out on the plains, and then crossed the river by the dugout to arrive at Chief Chitambo’s village.

A lifeline for wildlife

The next day, it’s a quick, early morning bowl of oats with honey and peanut butter, then a dash to meet the African Parks team now working to protect these vast Bangweulu Wetlands – a name in the Bembe language that means ‘where the water meets the sky’ – so vast it’s as if there’s no horizon. At the African Parks’ Nkondo headquarters, we’re met by engaging ethno-biologist Clemmie Borgstein and friendly camp dog Bullet.

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari lodges and campsites where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities? You can plan and book your African Parks safari to Bangweulu Wetlands and other parks by clicking here.

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari lodges and campsites where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities? You can plan and book your African Parks safari to Bangweulu Wetlands and other parks by clicking here.

“Bangweulu is one of the most important wetlands in Africa, fed by 17 rivers and drained by just one,” Clemmie explains. “Its story starts in the hills of Lake Tanganyika, where the Chambeshi River streams out from the rocks and down to the Wetlands, delivering a seasonal flood that inundates the plains. The water rises through a shifting complex of channels until it is finally released into the Luapula River, which drains out of the swamps and curves in a great arc to feed into the Congo River system and eventually makes its way to the west coast of Africa to enter the Atlantic Ocean.”

African Parks joined forces with six Community Resource Boards and Zambia’s Department of National Parks and Wildlife in 2008 to create the Bangweulu Wetlands Project. Since then, this community-owned protected area (not a national park) has become a lifeline for wildlife and 60,000-odd people who live within its boundaries and rely on its natural resources.

“This is home to the last significant population of black lechwe and over 400 bird species, including the rare shoebill, but what’s even more unique about Bangweulu is the interface between people and nature,” Clemmie continues. “We can’t lose this landscape to people – and we can’t lose the people to this landscape.”

Smiling, good-natured Lloyd Mulenga, Bangweulu’s community manager, is itching to get going. First up is a visit to the current Chief Chiundaponde to pay our respects and for His Excellency to endorse the expedition’s Scroll. The Chief is fascinated by the Defender 130s and insists on getting behind the wheel, all “ohs and aaahs…so much space” – until he spies the toy snake on our dashboard. He exits the Landy with a speed that belies his age, then doubles over with laughter when Ross assures him that it’s fake but very good at deflecting the interest of pesky traffic cops.

The people’s park of Bangweulu

The next stop is Mwushi Primary School; the teachers and children turn out in huge numbers and perform a comical skit, acting out the stalking walk of shoebill and the massing of black lechwe on the plains. They can’t take their eyes off Kingsley’s beard – after weeks of expedition life, it’s looking incredibly bushy – but only two are brave enough to take up the challenge of giving it a pull. The conservation art competition is a colourful success and it’s good to hear community leaders talking enthusiastically to the children about the importance of preserving the Bangweulu landscape.

In a big tent at the local clinic, we meet scores of poor-sighted elderly people who slowly filter in for eye tests and reading glasses; some brought on the back of bicycle taxis, others walking with the aid of grandchildren – as always, their appreciation is heartwarming.

Afterwards, we’re treated to a vibrant Bisa cultural event with a traditional lunch of catfish, cassava and chikanda (a polony-looking gastronomic delight made from the tubers of orchids and pounded groundnuts) and a drumbeating, gyrating ‘no-poaching’ song and dance performance; even the delightful midwife from the clinic jumps up and shakes her booty.

Bangweulu is a people’s-park, divided into swamps, vast plains and agricultural lands – it feels like time has stood still here. We’re keen to reach ‘where the water meets the sky’, so tackle a long dirt track through vibrant villages to reach the heart of the wetlands. Men in jackets and ties on bicycles and brightly dressed women in kangas and headscarves throng the road, many carrying plastic chairs to their simple mud-bricked, thatched-roof churches. Children shout greetings of ‘How are you-you-you?’ and the sounds of Sunday singing and harmony fill the air.

Good humour and a touch of madness

Our wild Nsobe Campsite is idyllic: a little island of trees on a large old antheap that, in the wet season, stands above the flooded plains, with just a simple circle of stones for a fireplace. The surrounding grassy plains are dotted with hundreds of gnome-like, grey termitariums. We dress up one solitary little fellow with a scarf, beanie, sunglasses and binoculars, name it ‘Norman No-mates’ and invite him around for a braai… our expeditions always run on good humour with a touch of madness!

Beyond our base camp, we’re ecstatic to see thousands of black lechwe and tsessebe amassed on the plains, with vast flocks of wattled cranes soaring and dipping like a synchronised aerial ballet. We learn that zebra, puku, waterbuck and buffalo have been re-introduced, the shy sitatunga, oribi and reedbuck are flourishing, and cheetah are back after a century’s absence. This is also the land of the elusive shoebill.

It’s not easy being a shoebill

Knowledgeable birding guide Webby Mweya takes us into the wetlands. Poling slowly through the extensive stands of papyrus, passing fishing villages, handwoven reed fish traps and chattering families navigating the channels in their narrow dugouts, we nose into a quiet backwater and find what we’ve been hoping for – one of Africa’s rarest and most curious birds. “Look!” says Webby with excitement. “You can see she is relaxed – eaten too many barbel fish! This shoebill’s name is Hope. She was rescued as a fledgling and then returned to the swamps by Maggie; you must meet her.”

“It’s not easy being a shoebill,” Webby remarks as we take a meandering route to the shoebill rehabilitation facility at Chikuni Island, the only one of its kind in the world. “Fire is a big threat to their nests; eagles and crocodiles take the eggs, and sometimes fishermen steal them. These birds are sought-after in the illegal bird trade. But we now have guards to watch the nests day and night.”

Considering Zambia for your next African safari? Read more about a safari in Zambia here, or check out our ready-made safaris here.

Considering Zambia for your next African safari? Read more about a safari in Zambia here, or check out our ready-made safaris here.

And so, we meet Maggie Hirschbauer, the dedicated shoebill researcher. Armed with a giant, muppet-like puppet, she greets us with “Shhhh!” This is a quiet zone; she doesn’t want the birds disturbed by noise. What follows is a fascinating glimpse into the secret life of shoebills. Just above a whisper, Maggie tells us that Bangweulu is their southernmost range, and there are no more than 8,000 birds left in the wild, existing in a handful of habitats between Zambia and South Sudan. Shoebills live for over 30 years but, as Maggie explains, they practice siblicide, so she removes the second egg and hatches it in an incubator when possible. Raising them isn’t easy either; to stop the chicks from getting used to humans, Maggie dresses in a dark ‘abaya’ and uses the shoebill puppet as a substitute parent.

Silently, we get to observe three adult birds in their bomas; Maggie will release them when Zambia’s annual three-month fishing ban begins in December, and people leave the swamps. Walking to the edge of a channel, she slips off her shoes and wades in to add symbolic Bangweulu water to the expedition calabash, the fifth such ceremony of this Afrika Odyssey expedition.

Our minds stuffed with shoebill info, we wander back to camp through the herds of black lechwe and notice something strange. The air is full of flying spider webs – long, trailing strands of silk being blown by the wind that gets caught in the Defenders’ radio aerials like flying pennants. We stop to take a closer look. The grassy plains are covered in cobwebs, a shimmering sheen stretching as far as the eye can see, glowing gold and red in the rays of the setting sun. It’s stunningly beautiful and adds a special something to Bangweulu’s magic.

The conservation economy of Bangweulu

Our last night is spent around the campfire with park manager Phil Minnaar and the Bangweulu community board members. Sprinkled with Phil’s entertaining bush pilot stories, we learn that the black lechwe population has recovered from 18,000 to over 40,000 today, fish stocks are increasing, poaching is under control, tourism numbers are on the rise and community enterprises (fisheries, honey production and lechwe off-takes) are generating more and more income for the Bangweulu people every year.

“When I arrived here, there were only three small stores in Chiundaponde village, and basic goods were in short supply; now, there are over 30 shops and other businesses, all driven by this conservation-based economy,” says Phil.

As the campfire burns low, Sheelagh opens the Scroll and reads Maggie’s heartfelt words:

“The shoebill… A massive flying creature that is utterly unique. Shy, sensitive, secretive, yet it carries a stature to intimidate even the strongest men. The shoebill is Bangweulu’s icon and flagship species because the land, water, community and bird are inextricably linked. If this habitat of vast open sky, fresh crystal-clear water, and variable vegetation of floating grasses, sedges, reeds, and papyrus suffer, if the fish dwindle, the shoebill will disappear – they have nowhere else to go. People, too, rely on this habitat; fishing is the largest economy in the region and forms the undercurrent of their culture. It has been my greatest privilege to know this species and see how the community living in these wetlands is engaging in their conservation. This continued involvement and spread of knowledge of the importance and rarity of these unique creatures will ultimately keep them alive for generations to come.”

It’s a poignant ending to a frenetic and fascinating few days in this ageless landscape. Ahead of us lies an exciting route to reach Malawi, country number four, on this journey to connect 22 African Parks-managed protected areas in 12 countries.

Resources

Read more about Bangweulu Wetlands, a place where water meets the sky, here.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()