Around 17 July 2021, a hunter shot a massive elephant bull (a tusker) in the Controlled Hunting Area (CHA) CH8 in the Chobe region of Botswana. The hunt was legal from what we can gather (i.e. conducted with the requisite permits, licences, etc.). According to the owner of the hunting operation that led the hunt, it was conducted ethically. What this means is not entirely clear as no further details were forthcoming despite repeated requests. The hunting operator was cagey, as is often the case.

The measurements for this bull were as follows:

- 108-pound (49 kg) tusker (mass of the heaviest tusk or an average of the two tusks)

- 57 inches out (144 cm) (length of the tusks from the lip to the tip)

- 19 1/2 inches at the lip (49.5 cm) (circumference of the tusk at the lip)

These measurements provided by our sources could not, unfortunately, be verified. The owner of the concession, Thys de Vries, responded as follows:

Unfortunately, I cannot comment on your query (for reasons I am sure you are aware of with the social media frenzy shit storm that happens when things go public). All I will say is it was an ethical, legal hunt within our CHA CH 8 Concession out of an overpopulated Botswana elephant population.

This was supposed to be a short, sad story on the death of another great tusker at the hands of a wealthy hunter armed with a high-calibre hunting rifle. Instead, it has turned into a rather tricky, often intensely personal, exercise in considering all the stakeholders in the Botswana hunting melange – the rural communities, the trophy hunters, the Botswana government and, not least, the elephants. The government of Botswana and the Botswana Association of Wildlife Producers, unlike the hunter, were refreshingly forthcoming with facts and figures.

Declaration

I must admit at the outset that I consider trophy hunting to be archaic and distasteful. I think it will eventually be consigned to the scrapheap of humanity’s abuse of nature. But I might be wrong. I cannot, in good conscience, not examine why I feel like this and ask if my feelings are justified while accepting that virtually nothing in this world is black or white, wrong or right. I must admit that my perspective is coloured by genetics, upbringing, education, experience and those with whom I have associated. The revulsion I feel about trophy hunting is not necessarily correct, right or even justified – no matter how real it is to me.

Some background: I wasn’t raised fishing and hunting. My parents hated guns, and no amount of begging could convince them to give me a pellet gun. We never talked about hunting; the activity was entirely beyond our frame of reference. We ate meat, and I can’t recall ever discussing where it came from or considering the living conditions of the animals we braaied on summer Saturday afternoons. I still eat meat, although seldom, and only if I am relatively satisfied that the animal wasn’t treated with cruelty.

When I left university, I trained to be a guide and in the course of the training, I had to learn to use a high-calibre rifle in case I should ever have to defend my guests from a charging animal.

I have shot animals.

The first impala I shot left me awash with wildly differing emotions. I fired the rifle and ran from cover to find the ram, eyes open, tongue lolling, the final twitches of death shuddering through him. Tears flowed. I felt ashamed and sad and elated all at once. I dragged the hapless ram back to camp, where a line of cheering people clapped me on the back and told me how clever I was. I felt elated again. Then I felt sad again. This was the final test I had to pass to become a guide – it tested my skill with the weapon and the bushcraft I had learnt. We ate him a few days later.

I have shot other impala for the pot, thankfully all clean hits – this was harvesting from a vehicle for food. I did not feel awful about this – it would have been illogical as a meat-eater. We are predators – human beings have consumed animal products for millennia. Our physiologies are adapted to this (even if we are not obligate carnivores).

A few years after my first impala hunt, a runaway fire caught a herd of elephants in the Kruger National Park. The traumatised animals came onto the concession where I worked, and the Kruger section ranger asked me to help him euthanase them – they were horrifically burnt and suffering terribly. I remember standing in front of the first big cow. She turned to face us, her head held high, ears out.

We shot her.

I have to confess to a certain sense of exhilaration as the massive animal fell. I felt, for want of a better term, powerful. For me, this quickly faded to sadness. I can only assume that the thrill is more permanent to people who repeatedly hunt – that the rush of standing in front of an adult elephant, front on, and then ending its life is something they crave.

Hunting in Botswana – lifting of the moratorium

On 23 May 2019, the Botswana Government lifted the five-year moratorium on hunting. This created a predictable flaring of the pro versus anti-hunting rhetoric, the same arguments rehashed and shouted from various soapboxes.

Regardless of how you feel about the trophy hunting of elephants, elephant populations in Botswana, what constitutes an ethical hunt (if such a thing exists), research shows that the numbers of tuskers like the bull shot on 17 July are in decline. This is not the fault of all trophy hunters operating today but rather a legacy of centuries of ivory trading, poaching and trophy hunting.

Why the need for big ivory?

Poachers will target so-called ‘hundred pounders’ or any large tusked elephants – the more the ivory, the greater the pay. However, it is not clear why some trophy hunters, who bleat about how they only hunt because they love nature, would seek to shoot the remaining big tuskers. It is also unclear to me (as a non-hunter of trophies) why an animal with big tusks is more rewarding to shoot than one with smaller tusks – the tracking, risks, etc., are the same. There is nothing more dangerous or difficult about hunting a big tusker compared with a tuskless animal.

Unfortunately, to my mind anyway, the desire to shoot large-tusked bulls must surely have its roots in the human ego and not in the love for tracking, nature or ‘fair chase’. It must come from the desire to say ‘mine is bigger than yours’. The same goes for record antelope horns. We assign arbitrary human value to a genetic expression.

At the same time, I must acknowledge that by bemoaning the hunting of big tusked elephants, I am also assigning an arbitrary value to elephant tusk size and suggesting that, if people insist on shooting elephants, they choose ones with smaller tusks. Smaller tusked elephants would be justifiably alarmed by this – who is to say that they are of less value to the species in general than their larger tusked compatriots? I am not aware of any science that suggests this. To the average marula or knobthorn tree, the ideal elephant is a tuskless one.

That said, I don’t think anyone – from the most ardent hunter to the most rabid anti-hunter – would disagree with the assertion that it would be sad to lose the last remaining tuskers. They’re impressive beasts, fantastic to photograph, and evolution has dictated that they are here, so let’s not make a dodo or quagga of them.

In the case of the bull that started this reflection, perhaps the hunter thought he was beyond breeding age – we don’t know because the hunter wouldn’t comment. Botswana Wildlife Producers Association committee member, Debbie Peake, justified the shooting of tuskers as sustainable because, by the time their tusks reach 100 pounds, they have already mated any number of times and, therefore, their genes exist in the population.

Dr FJ Verreynne (BVSc, M.Phil Wildlife Management), Coordinator: Research and Veterinary Working Group Botswana Wildlife Producers Association notes the following:

‘Controlled hunting of elephant bulls in Botswana under the international CITES annual export quota of 400 individuals is part of the sustainable utilization policy of the Government of Botswana. There is no legal ceiling on the size of the tusks to be hunted although tusks of less than 11kg may not be exported. It is therefore expected for bulls with bigger tusks to be hunted in Botswana. It is encouraged to hunt older bulls which genes have already been spread within the wider population.

‘BWPA acknowledges the intrinsic value of big tusk elephant bulls. We have therefore approached the DWNP in December 2020 to fund and fit monitoring collars on ten of the big tuskers known to be present in Northern Botswana. This will allow the Association, anti-poaching authorities and our members to look after the animals, and protect them against poaching and hunting. We have received no response from the Department on our request and therefore refer all enquiries regarding the hunting of big tusk elephant bulls to The Director: Department of Wildlife and National Parks.’

This does not explain the research showing a decline in large tuskers. It gives no hard facts about how many youngsters the tusker may have sired or how many he could have sired before being shot. In theory, elephant bulls are perfectly capable of breeding almost until they die. If there was a chance that this animal could breed again, then the hunt reduced his genetic legacy. Indeed research shows that far from slowing down as they get older, 50-year-old bulls move twice as fast and over 3.5 times the area when in musth compared with their 20-year-old counterparts. Other research (here and here) shows that elephant bulls of all ages are important in elephant society – as mates, mentors and disciplinarians.

Was the sacrifice of this bull worth it? Well, let’s examine what these hunts are worth financially.

Background to current Botswana hunting

The Botswana Government argued, in broad strokes, that the hunting moratorium should be lifted because:

- There was inadequate community consultation when the ban was imposed;

- The ban was not based on scientific evidence;

- There had been an increase in human-elephant conflict (HEC);

- There had been an increase in human-predator conflict; and

- The lack of hunting was having drastic adverse effects on rural livelihoods.

The Ministry reasserted Botswana’s sovereign right to lift the hunting ban and claimed that all stakeholders were consulted (NGOs, conservationists, scientists, leaders of neighbouring countries). The decision was made in the best interests of the rural communities and aimed to stem HEC and encourage communities to support sustainable use conservation and tourism. It also claimed that Community-Based Organisations (CBO) that have marginal land would again benefit.

The statement claims that ‘following the implementation of the moratorium, it became abundantly clear that non-consumptive practices on marginal lands did not contribute to economic development.’ (For complete statements from the Botswana government, see here and here.)

I am not sure how seriously anybody takes the justification of hunting on the grounds that it will reduce HEC. It stretches the limits of credulity to suggest that the hunting of 277 elephants from a population of some 130,000 will stop or minimise HEC. However, the economic arguments are worth considering and, for anti-trophy hunters like me, they’re even more critical.

How much money and where it is going?

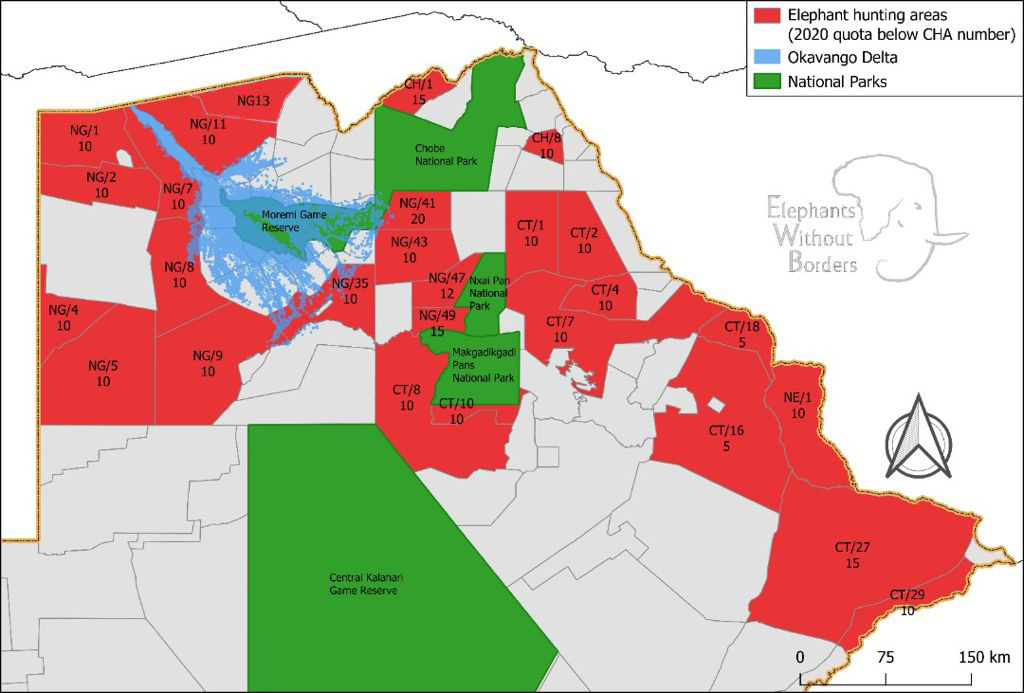

What follows applies to the Special Elephant Quota (70 animals) and not the Citizen Quota or the Community Concession Quota (see below in the section ‘From the Director-General’ for further explanation).

The government put the 70 elephants up for auction. The quota was allocated to marginal areas that do not benefit from photographic tourism because they are unsuitable for various reasons. In broad strokes, hunting operations bid for allocations of ten elephants at a time. Because of the travel bans caused by the Covid 19 pandemic, the quotas for 2020 were rolled over to 2021.

The ten-elephant quota bundles sold for between BWP 3.6 million (USD 326,520) and BWP 4.75 million (USD 430,825). A seventh package didn’t meet the government’s reserve price of BWP 2 million. The most expensive hunt went for USD 43 000 per elephant. (https://www.bloombergquint.com/onweb/botswana-sells-elephant-hunts-for-as-much-as-43-000-per-animal)

The Special elephant quota generated a total of BWP 25.7 million (approx. USD 2.3 million) for the Conservation Trust Fund, which is administered by the Ministry of Environment, Natural Resources, Conservation and Tourism. People in rural areas can apply to the fund for various development projects (see comment below from the Department of Wildlife and National Parks).

After the auction, the hunting operators sold the hunts at a profit. This season, the prices from various operators ranged from US$ 28,000 to US$ 80,000, depending on the area. This is the package cost of the hunt and will include accommodations, professional hunters fees, government hunting fees, conservation fees, trophy fees – all of which vary according to the area. Some areas are difficult to access, have rustic camps, are challenging to hunt in and have more people living in and around them. Others are wilder, easier to access and have luxury camps.

In addition, the government collected around BWP 5.74 (USD 521,000) million from license fees.

Meat from hunts is distributed to residents or adjoining communities where possible, and processed meat generates significant revenue for local-level households. It is difficult to quantify this, but the amount probably extends to a few hundred thousand pula over all the concessions (according to the Botswana Wildlife Producers Association).

From the Director-General

Below is an outline of the hunting process and the benefits outlined to me by Doctor Kabelo Senyatso, director-general of the Department of Wildlife and National Parks (DWNP).

Simplified, the hunting quota in Botswana consists of 3 components:

- Community/concession quota. The DWNP issues a quota to Community Based Organisations (CBOs), which are legal entities representing communities where the CBO exists – or concessionaires of particular Controlled Hunting Areas (CHAs). They then dispose of their quotas as they see fit, e.g. some auction their quotas as single lots, some in several lots. Some enter joint venture partnerships where profits are shared after hunts. Income from these sales goes directly to the CBOs.

- Citizen quota. These are issued to CHAs and not CBOs. They are disposed of via a raffle system to citizens. They are transferable only once to other citizens, and during the transfer, the winner of the raffle sells off their right at a rate negotiated with the ‘purchasing citizen’.

- Special elephant quota. These are auctioned by DWNP, and funds go into a Conservation Trust Fund (CTF) managed by DWNP. The CTF is then used to support (i) elephant conservation projects and (ii) community livelihoods projects in the elephant range. One hundred per cent of the special elephant quota goes into the CTF, from which elephant conservation projects (70%) and community livelihood projects (30%) are funded.

Added to the above, the CBOs also charge hunting parties various fees associated with the hunts, all of which then add to the average price of a hunt.

Doctor Senyatso went on to say, ‘In June 2020, we reached a milestone of BWP 100,000,000 (USD 9,070,000) of the CTF having been disbursed for elephant conservation and upliftment of communities in the elephant range (since CTF inception in 1999), which is worth celebrating.’

Conclusion

Even the most ardent anti-trophy hunter cannot fail to be impressed by some of these figures. Only the most heartless and ignorant (of facts at ground level) would claim that the poor people living in these marginal areas do not deserve to benefit from maintaining the wildlands and not turning them into cattle ranches and ploughed fields.

That said, I find the justification that wealthy hunters are saving marginal wildlife areas offensive – even though it is inescapably true in some cases. The logic broadly being that unless the moneyed hunter who loves nature can get something out of that nature (in the form of a trophy, an adrenaline rush etc.), they will not invest in protecting it. But the same could be said of any commercial tourism operation – all the employment and other benefits that come with a prosperous business would disappear without profit – their investors would put their money elsewhere. Many luxury photo tourism operations have a significant environmental footprint per guest and, therefore, are extractive and damaging. Both trophy hunting and much photographic tourism are subjecting nature conservation to forces of the ‘market’. This is despite the fact that the ‘market’ is utterly oblivious to its effect on the environment in countless industries.

It is also beholden on me to acknowledge the contribution that trophy hunting operations make to rural people’s well-being and economic development if the figures quoted above are accurate. They come from two independent sources and I do not have any reason to doubt them at this stage.

So, where does that leave the argument?

I don’t know. But I do know that productive engagements like the ones I had with the Botswana government and with the Botswana Association of Wildlife Producers are extremely helpful. As offensive as I find the idea of shooting an animal minding its own business, stuffing it and mounting it on a wall, I can accept that the practice is not entirely harmful, albeit a practice I do not understand and still believe will disappear in the future. For anti-trophy hunters, the challenge remains – who will fill the financial gap if/ when the trophy hunters shut up shop?

Finally, back to the tusker shot on 17 July. I do think there is little value in shooting tuskers for the sake of it. Detailed research shows that the practice is reducing their genetic legacy. They provide no more meat, tracking challenge or adrenaline rush to the hunter than smaller-tusked elephants.

In all of this, let us try, impossible as it may be, to keep our minds open, our egos at bay and to be aware of where our particular perspectives originate.![]()

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()