African Wildcat

“In ancient times, cats were worshipped as gods. They have not forgotten this…” ~ Terry Pratchett

A cat stretched out on the best seat in the house, lazing in the sun, is the very picture of domestication. They purr contentedly and rub up against their human servants’ ankles, demanding to be timeously fed, or regard the excitable family dogs with a kind of contemptuous smugness from a place of safety. Yet as every cat owner knows, there are times when these cats stalk their surrounds, pupils wide and teeth and claws at the ready, embroiled in their own hunts, scuffles, and romances. In these moments, domestic cats don’t appear particularly domestic.

Their instincts are a throwback to a time when their ancestors stalked Africa and Asia, surviving by their wits and reflexes, and preying on any number of small mammals, birds, amphibians, and arthropods. Some of these cat ancestors were drawn to human settlements and abandoned their wild existence to enslave their human owners. Yet others remained wild and, to this day, African wildcats continue to live as they have for thousands of years. Rangy and hard-bitten, they slink through the continent’s savannas, forests, and wetlands – seldom seen and often overlooked but every bit as wild as the other members of the feline family.

The true ancestors of domestic cats

In many ways, African wildcats are to cats what wolves are to dogs, with some important differences. While a history of domestic cats may seem out of place in an article on a wild creature, it goes to the heart of understanding the challenges faced by conservationists in classifying and protecting African wildcats.

The process of cat domestication was a complex one, and fossil evidence is in short supply, making piecing the events together somewhat tricky. Historians and scientists now believe that domestic cats went through two different periods of domestication – first in south-west Asia around 10,000 years ago and then, once again, in Egypt about 3500 years ago. Genetic analysis indicates that domestic cats may have two different source populations that can be traced to different periods but confirms African wildcats are the true ancestors of domestic cats.

As with dogs, scientists believe that cats were domesticated along a commensal pathway. Essentially, the wildcats (initially in Egypt and the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East) would have been attracted to human settlements for a variety of reasons, including warmth and increased food availability. Over time, people realized the benefits of keeping cats for pest control and gradually a shift took place from a purely pragmatic mutualistic relationship to one that extended to companionship (and selective breeding). A skeleton of one wildcat uncovered in Egypt and dated to somewhere between 3,600 and 3,800 years ago shows evidence of healed fractures that suggest the injured cat was cared for by a human.

Unlike dogs, modern cats have retained more genetic and behavioural similarities with their wild relatives, most likely because, while domestic dogs have been largely isolated from their ancestral wolf populations for thousands of years, domestic cats have continued to breed with their wild cousins. This, in turn, has ultimately led to one of the greatest threats facing wildcat populations not only in Africa but across the globe.

What’s in a name? Everything.

Given that domestic cats have only been “domesticated” for around 4,000 or so years and have continued to breed with their immediate wild neighbours, they are almost indistinguishable genetically from wildcat populations. These genetic and morphological similarities have made the classification of several smaller cat species extremely complicated and often contested. So much so that even the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature only confirmed the domestic cat as a separate species in 2003.

The Felidae family or cat family evolved around 10 million years ago, and the Felis genus diverged some 7 million years later. This genus of small and medium-sized cats encompasses several different species and subspecies including domestic cats (F. catus), the jungle cat (F. chaus), the black-footed cat (F. nigripes), the sand cat (F. margarita) and the African wildcat (F. lybica).

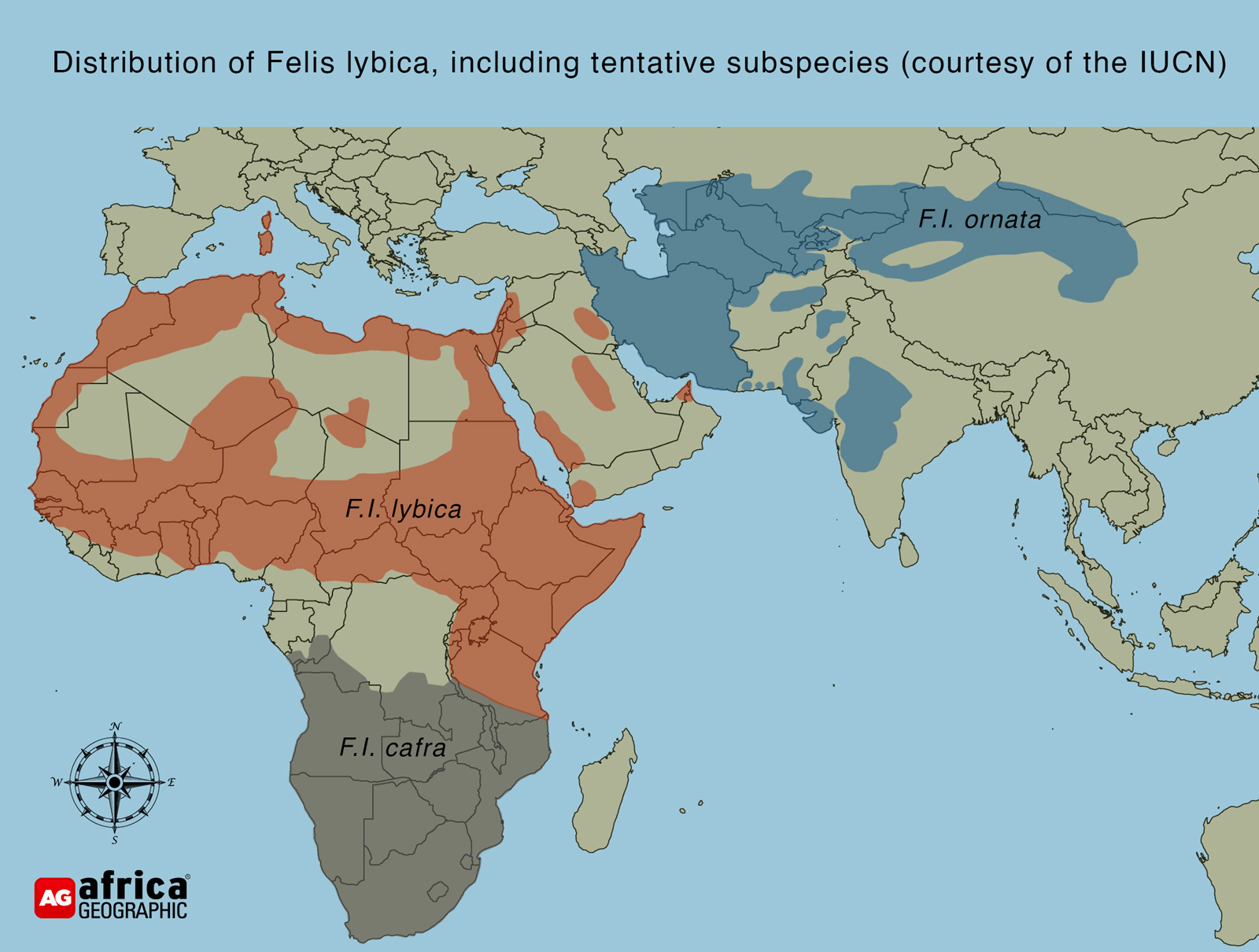

The IUCN Red List still lists the African wildcat as a subspecies of the European wildcat (F. silvestris), which in turn has been allocated a conservation status of “Least Concern”. However, this is likely to change after a 2017 report by the IUCN’s own Cat Specialist Group recognized the African wildcat as a separate species – Felis lybica. The report also tentatively proposed three different subspecies distinguished primarily on distribution: F. l. lybica (found in North Africa), F. l. cafra (the Southern African wildcat) and F. l. ornate (found in Asia).

Species and subspecies distinctions may seem pedantic in animals that are almost identical on so many levels, but these distinctions are fundamental to conservation efforts. Classification as a separate species allows zoologists to draw substantive conclusions as to the animal’s conservation status. It also makes the process of identifying specific threats more selective. In the case of the African wildcat, it is the threat to its genetic integrity that menaces the population.

The conservation (cat)astrophe?

In a 2010 study by the Ecology Global Network, scientists estimated that there were some 600 million domestic cats in the world. By contrast, while there are no estimates of African wildcat populations (the logistics and their widespread distribution make counting them an almost impossible task), there is no doubt that they are massively outnumbered.

As available wild spaces have vanished one by one, human populations have expanded, bringing domestic and feral cats with them. Given their genetic similarities, sexual encounters between domestic cats and wildcats are inevitable, and hybridization is common on the fringes of wildcat distribution ranges.

In a 2014 study, researchers concluded that in South Africa at least, levels of hybridization are still relatively low, especially in the Kgalagadi Transfrontier National Park which is a population stronghold for the African wildcat. The DNA samples collected from wildcats that indicated the highest levels of interbreeding came from individuals in the Kruger National Park. Given the high human population density on the Park’s border, this is hardly surprising.

A project such as Alley Cat Rescue aims to mitigate this impact through domestic and feral cat sterilization programmes, focussing their attentions on specific border areas. These programmes also implement vaccination schemes to reduce the risk of disease transmission between domestic and wildcats.

Is it a wildcat or an escaped moggie?

To the uninitiated, an African wildcat could look for all the world like a slim domestic cat. There are, however, subtle differences between the two. African wildcats are slightly taller than the average domestic cat, and their legs are proportionately longer, which gives them a more upright posture, particularly when sitting. Their walking gait is more like that of a serval or cheetah than the average domestic cat.

The variety seen in domestic cat coat colours is a product of selective breeding, and this variety is not reflected in the coat colours of the African wildcat. Instead, their almost uniform colour ranges from red to sandy and brown to grey, with very faint stripes known as the mackerel-tabby pattern. The end of their tails is ringed with black, the backs of their ears are characteristically russet, and the underside of their paws are pitch-black.

Behaviour

Like their domestic congeners, African wildcats have proved to be extremely adaptable and, as a result, occupy a wide number of different habitats from deserts and grasslands to savannas (though their range does not extend to rainforests). Their diets are varied and unselective – anything, including small mammals, birds, reptiles, and arthropods are all targeted. Some individuals have even been known to prey on young livestock animals such as lambs or kids, putting them at risk of conflict with farmers. African wildcats are reliant on keen senses, particularly their hearing, to identify prey. Their ambush approach is well-honed, and they demonstrate extraordinary patience in stalking – often biding their time for hours at a time.

One of the common effects of domestication (seen in domestic dogs, cats and other animals) is an increased breeding frequency. Female domestic cats reach sexual maturity as early as four months old and are capable of producing three litters of kittens every year. In contrast, the African wildcat generally only produces one litter during the wet season.

Being one of the smallest members of the cat family, their natural predators are numerous and include the larger cat species and birds of prey.

Conclusion

For the most part, African wildcats are somewhat underappreciated – they look so similar to feral cats that they are often dismissed as such, despite their status as one of the “Secret 7” (serval, wildcat, large-spotted genet, civet, porcupine, aardvark and pangolin). Yet these gangly, tough little cats are just as interesting, untamed, and fierce as their iconic big cat cousins.![]()

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()