THE AFRICAN CAT YOU'VE NEVER HEARD OF

I was used to working in the savannahs of eastern and southern Africa, where the animals I studied roamed in full sight. I was used to the relative comfort and safety of getting around in a 4×4, and my camera went everywhere with me. Then, in 2010, I arrived in the Central African country of Gabon to begin studying the African golden cat in and around Ivindo and Lopé National Parks. I stubbornly kept my camera with me for the first few days but soon realised it slowed me down. I could no longer rest it on my lap as I scanned the horizon. I had to carry it for nine hours daily as I surveyed the humid forest on foot. I had to be ready for a hasty retreat in case I stumbled upon elephants – quite easy to do when visibility is restricted to a few metres by thick vegetation.

A mandrill caught on one of the author’s camera traps, just one of many wonderful forest creatures Laila recorded.

A black bee-eater perches on a forest vine.

©Laila Bahaa-el-din

Of course, not carrying my camera meant I could not photograph the gorillas and chimpanzees I encountered or the colourful birds that provided the soundtrack to my exploration. But soon, I accepted that my eyes (and camera) would no longer be my key tools. Now I needed to rely on my ears and nose to experience this new wilderness and to stay safe.

Of the African cats, the one you’re least likely to have heard of is the African golden cat. It lives in the rainforests along the Equator, is very shy, and successfully avoids people – that is until it falls into a hunter’s snare. Imagine a stocky caracal but without the pointy, tufted ears. It weighs 10 kg on average and, despite the “golden” moniker, it varies in colour from red to grey and sometimes black. It generally has markings on its underbelly and the inside of its limbs, but they sometimes extend across the whole body. We know almost nothing about its behaviour and breeding biology in the wild. This tough cat briefly found fame a few months ago when a film showing it hunting red colobus monkeys was released online (watch it above, it’s worth it!). A handsome creature, the golden cat is often called the leopard’s little brother. When it has the misfortune to be captured by hunters, its skin is used for ceremonial purposes, and its meat is eaten.

Camera traps provided me with eyes to see things my ears and nose were sensing

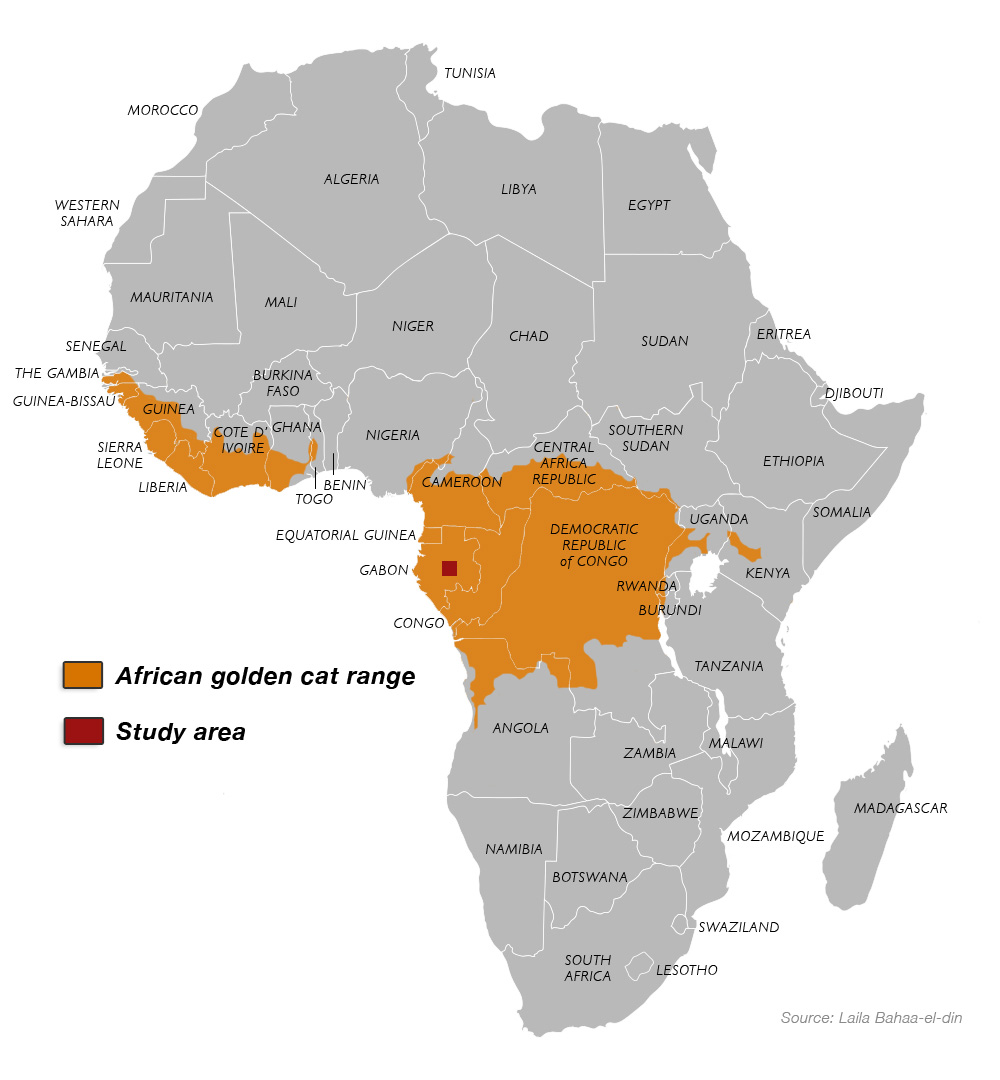

So what was I doing here, deep in the forests of Gabon? My study aimed to estimate how many golden cats there are and to see how human activities affect them. I collected data from six different areas in Gabon, some of which were protected, some were subject to logging, and some were regularly hunted.

The camera trap is the obvious tool to study such a shy animal in the forest. Set up to work remotely; the camera is activated by an infrared sensor every time an animal passes by. These traps gave me the eyes to see everything my ears and nose were sensing as I walked the forest trails. Looking through the images was the highlight of my work – a silverback gorilla proudly standing his ground, a giant pangolin searching for termites, a goshawk clasping a squirrel it has just caught, and some elephants greeting each other. Sadly, there was also the occasional hunter, catch in hand. But most importantly, there were many photos of golden cats, providing me with the data I needed to make my assessment.

I felt honoured to be let in on its secret life

We have learned so much from these photographs. It is clear that golden cats are active at all times of day and night, and they like to make use of trails opened up by elephants and people, and they are indeed solitary. Interestingly, their coats vary in colour and pattern, even within one small site.

From images of a female carrying her prey past a camera to videos of a youngster batting at the camera with his paw, the mysterious golden cat was being revealed to me daily, and I felt honoured to be let in on its secret life. On one exceptional day three years into my study, when I was carrying my camera with me, a beautiful golden cat female allowed me to see and photograph her. I lowered the camera with shaking hands to watch her disappear into the forest. I turned to Arthur, my field assistant, and we grinned madly at each other as he whispered ‘chat doré’ (golden cat in French)

Dependent on forests, this plucky little cat will become even rarer

Then came the time to count the cats. You can identify individuals of other cat species by their coat patterns. Take, for example, a leopard’s rosettes or a tiger’s stripes – each individual is different. Although it’s the same with golden cats, their markings aren’t so easy to see in camera trap photographs because they are smaller and on less visible body parts. So, as I wasn’t 100% confident of my identifications, I enlisted two cat researchers to double-check my efforts. One of them described the exercise as the most frustrating thing he had ever done! But we got there in the end, and we can estimate the number of golden cats for the first time.

These figures will be officially released in a few months. As expected, golden cat numbers were at their highest in the pristine, undisturbed areas. Though hunted at low intensity, the village hunting area held very few golden cats, with wire snares proving to be the greatest threat. These snares are indiscriminate killers and, when not checked regularly, can be wasteful as animals are left to rot. There is also evidence from other areas that golden cats are highly sensitive to hunting. In areas where hunting intensity is high, golden cats are virtually extinct.

The golden cat is dependent on its forest habitat – a precarious lifestyle because trees are often considered a resource to be extracted by people. With African rainforests predicted to host major booms in mining activity and clear-cutting for development and oil palm plantations, this plucky little cat will become rarer and rarer, along with its fellow forest dwellers such as great apes, forest elephants, pangolins and many more. But there is hope too! The population size of the golden cat at the pristine site was comparable with forest cats from other continents (such as the leopard cat in Borneo and the Ocelot in Belize, both of which have density estimates of between 10 and 16 individuals per 100 km2). This is an encouraging result for a previously considered naturally rare cat.

The experience of living in an African rainforest often left me breathless (and not just due to elephant-induced sprints). Light slanting through the dense vegetation that the golden cat calls home gave me a glimpse of what it will take to protect the species. If deforestation can be slowed and the use of wire snares for hunting bush meat reduced, Africa may well hold on to its only forest-dependent cat.

ALSO READ: Camera traps photograph black honey badgers in Gabon

Contributor

LAILA BAHAA-EL-DIN first escaped to Africa in 2007 after completing her degree in zoology at the University of Nottingham. She has since found it almost impossible to leave and has worked on research projects in eastern, southern, and central Africa. Laila’s work has thus far concentrated on the predators of land (cats) and sky (raptors). The golden cat project, funded by the global wild cat conservation group Panthera, is part of Laila’s PhD research with the University of KwaZulu-Natal and the Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU) at the University of Oxford.

LAILA BAHAA-EL-DIN first escaped to Africa in 2007 after completing her degree in zoology at the University of Nottingham. She has since found it almost impossible to leave and has worked on research projects in eastern, southern, and central Africa. Laila’s work has thus far concentrated on the predators of land (cats) and sky (raptors). The golden cat project, funded by the global wild cat conservation group Panthera, is part of Laila’s PhD research with the University of KwaZulu-Natal and the Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU) at the University of Oxford.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()