-

Cheetahs can breed year-round, but they time their reproduction to match the best prey availability

-

In places with clear wet and dry seasons, most cheetah pregnancies start in the wet months.

- Prey age matters more than abundance; younger prey is easier for cheetahs to catch.

-

Because cheetahs can adjust their timing, they may cope better in the face of climate change.

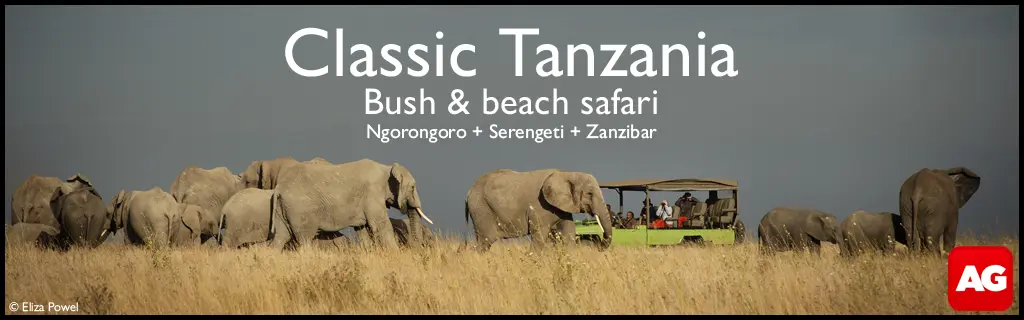

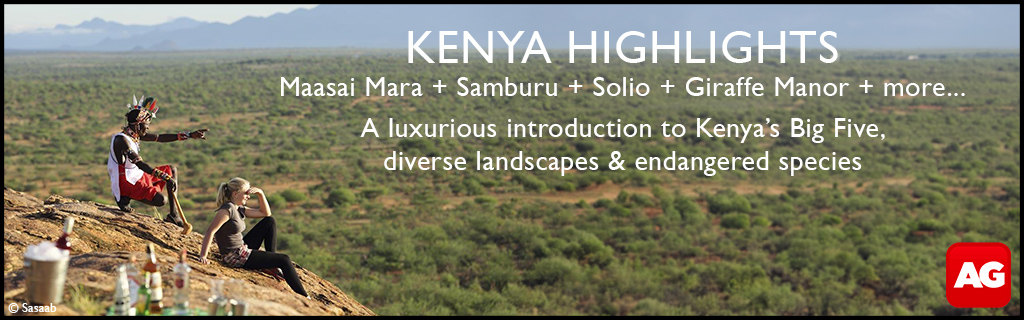

Want to see cheetahs on an African safari? Check out our safari ideas here, or let our travel experts plan the perfect African safari for you by clicking here.

Want to see cheetahs on an African safari? Check out our safari ideas here, or let our travel experts plan the perfect African safari for you by clicking here.

Breeding and hunting are both costly for predators. For a female cheetah, the energy demands of conceiving, carrying, feeding and raising cubs can stretch over almost two years. In that time, her chances of success depend not just on her speed, but on something less obvious: timing. A new study asks a simple question with complex implications: when should a “clever” cheetah breed to make best use of the prey available to her?

Seasons, prey and cheetah reproductive phases

Many African ecosystems are shaped by seasonal rainfall, with a clear wet season when grass flourishes and a dry season when food is scarce. In these landscapes, most antelope and other hoofed prey animals give birth during a relatively short period in the wet months. This creates a sharp pulse of small, vulnerable newborn animals that are highly profitable for predators. Other areas are more aseasonal: rainfall is more evenly distributed throughout the year, vegetation remains available for longer, and ungulates give birth over extended periods rather than in a tight baby boom.

The study, co-authored by scientists from Nelson Mandela University, University of Mpumalanga and Endangered Wildlife Trust, looks at how many prey animals are available. It also looks at which age classes dominate at different times of year. Neonates (animals younger than three months) are small and relatively easy to catch for cheetahs. Juveniles, between three and twelve months, are larger and more mobile but still less capable than adults. Adults, older than twelve months, are bigger, stronger and more dangerous to hunt. Earlier work has shown that cheetahs in southern Africa switch their diet between these age classes with the seasons: they rely heavily on juveniles and adults in the dry season and take almost no neonates, but shift to neonates and fewer adults in the wet season when a flood of young prey appears.

Against that backdrop, the cheetah reproductive cycle is long and demanding. A female can come into oestrus roughly every two weeks and is physiologically capable of conceiving at any time of year. Gestation lasts around three months. Cubs begin eating meat at about one month of age, but only wean at about four months. Mothers start bringing live prey when cubs are roughly two and a half to three and a half months old, and the cubs only begin to suffocate prey on their own between four and a half and six and a half months old. Independence comes late, at around 18 months of age. From conception to independence, a single reproductive attempt lasts about 21 months, during which the mother must repeatedly find adequate food for herself and her growing cubs. Because different phases demand different amounts and types of food, theory predicts that an optimally foraging predator should try to align the most demanding phases with peaks in accessible prey.

What the researchers tested

The research team analysed 246 cheetah litters monitored across multiple sites in South Africa, Namibia, Malawi, and Tanzania. These sites included fenced reserves, unfenced reserves and farmland. Using long-term rainfall data, they grouped sites into seasonal and aseasonal rainfall regions. They then used published information to identify the local breeding seasons of the main ungulate species present.

For each litter, the researchers estimated the month of conception. They made the assumption that it was three months before birth. They identified birth dates while correcting for the period when cubs remain hidden in dens and are not yet seen by observers. From birth, they projected cubs would wean at 4 months and eventually reach independence at 18 months. With these dates, they could ask whether any of the four key phases – conception, birth, weaning and independence – showed clear seasonal peaks. They could also tell whether those peaks lined up with the wet or dry season and with the prey birthing period, when neonates and juveniles are most abundant.

Their framework suggested that in strongly seasonal systems, conception might be expected to occur toward the end of the prey birthing pulse. Birth would then fall in the dry season, when neonates have grown into juveniles. Weaning and independence tend to align with subsequent prey birthing seasons, giving mothers and independent cubs access to easy-to-catch young prey.

What they found: flexible but patterned cheetah breeding

Across all sites, cheetahs could conceive and give birth in any month of the year. There was no overall difference between seasonal and aseasonal areas in the total number of litters conceived or born, confirming that cheetahs are physiologically able to breed year-round.

In seasonal systems, however, a clear pattern emerged. Among the 142 litters from areas with strongly seasonal rainfall, conceptions peaked between January and April, during the wet season and the prey birthing period. Nearly three-fifths of litters were conceived in the wet months. Births peaked between April and July, in the early dry season, and again, just over 60% of litters were born in the dry season. Weaning and independence did not show strong statistical seasonality, but most litters nonetheless reached these stages during prey birthing periods, when neonate and juvenile prey were abundant.

Statistical models confirmed that more litters were conceived during the prey breeding season and that this trend increased with rainfall. An interaction between rainfall and prey birthing season suggested that rainfall outside the main prey birthing window may act as an environmental cue, prompting females to conceive in anticipation of an upcoming wave of neonate prey.

In aseasonal systems, represented by 106 litters, the picture was very different. Conception, birth, weaning and independence were spread fairly evenly across the year, without strong peaks in any particular month. This fits the prediction that when neonate and juvenile prey are available for much of the year, there is no marked advantage to breeding at a specific time. Interestingly, a greater proportion of litters in aseasonal areas were successfully weaned and reached independence than in seasonal areas. That pattern suggests that a more consistent prey supply may ease the energetic bottlenecks faced by mothers and cubs. However, the study did not experimentally test the mechanism underlying this difference.

Why prey age matters

A central message of the study is that it is not just overall prey abundance that matters to cheetahs, but the changing composition of prey age classes through the year. Neonates and young juveniles are smaller, less coordinated and less experienced, which makes them easier and safer for a medium-sized predator to capture. They are also energetically profitable at precisely those times when mothers are pregnant, recovering from birth or supporting rapidly growing cubs.

By conceiving near the end of the prey birthing pulse in seasonal landscapes, a cheetah mother can benefit in several ways. In late gestation, when her own energetic needs are high, she can exploit abundant neonates that are easy to catch. During lactation in the early dry season, when she must find high-value meals but is no longer hindered by pregnancy, she can target larger juvenile prey. As her cubs approach independence, their first months of solo hunting tend to coincide with the next wave of neonate prey, which is critical for inexperienced hunters still developing their skills. In this sense, the cheetah appears “clever” not because of any conscious calculation, but because natural selection has favoured reproductive schedules that track predictable pulses of vulnerable prey.

Caveats and implications for cheetah conservation

The authors were cautious about over-interpreting their results. The breeding data come from monitoring programmes designed primarily for other purposes, so exact birth dates had to be inferred from first sightings and known denning behaviour. Some litters likely died before they were detected. If mortality is higher in certain seasons, that could bias the apparent timing of breeding. The analyses also demonstrate a strong alignment between cheetah reproduction and prey demography, but do not isolate prey availability as the only causal driver. Other factors, including photoperiod, rainfall patterns and broader environmental conditions, almost certainly play roles in shaping reproductive timing in cheetahs and other felids, and those roles remain to be fully understood.

Cheetahs are often portrayed as highly specialised predators with limited capacity to adapt to environmental change, and their low cub survival is a major concern. But this study shows a degree of behavioural flexibility. In seasonal systems, cheetahs appear capable of fine-tuning their reproductive timing so that conception, birth and cub independence align with favourable prey conditions. In aseasonal systems, they breed year-round and achieve higher rates of cub independence, apparently taking advantage of more consistent prey availability.

This flexibility is encouraging in a world where climate change and land-use shifts are altering rainfall regimes and potentially reshaping the timing of prey birthing seasons. An ability to adjust breeding schedules could help cheetahs persist. At the same time, the study highlights how dependent cheetahs are on predictable pulses of neonate and juvenile prey in seasonal systems. If that synchrony is disrupted, for example, by changes in rainfall that desynchronise plant growth and ungulate reproduction, raising cubs successfully may become more difficult.

By clarifying when and why cheetahs breed, this research helps identify periods when mothers and cubs are most vulnerable and when protecting key prey age classes is particularly important. It moves the conversation beyond simple counts of prey and predators to consider the timing and structure of their interactions. This is a crucial layer of understanding for anyone interested in the long-term future of cheetahs.

Reference

Annear, E., Minnie, L., van der Merwe, V., & Kerley, G. I. H. (2025). When should “clever” cheetah breed? Seasonal variability in prey availability and its effect on cheetah reproductive patterns. Ecology and Evolution, 15(6), e71655. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.71655

Further reading

- Read more about the cheetahs of southern Tanzania: A study aimed at aiding the conservation of Tanzania’s cheetahs reveals the secrets of the cheetahs of the Ruaha-Rungwa ecosystem

- Kalahari’s overlapping cheetah litters: A cheetah mother has been observed simultaneously raising two cheetah cubs of different age classes – behaviour never witnessed in the wild

- The Power of Unity – Cheetah coalition in Maasai Mara: This is the story of a cheetah coalition of five males – the Tano Bora coalition, meaning ‘The Magnificent Five’ – in Kenya’s Maasai Mara

- Want to know more about cheetahs? Read everything there is to know about cheetahs here

- Cheetah cub survival impacted by high-tourism areas: A study has found that high levels of tourism can have a negative impact on the rearing of cheetah cubs to independence

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()