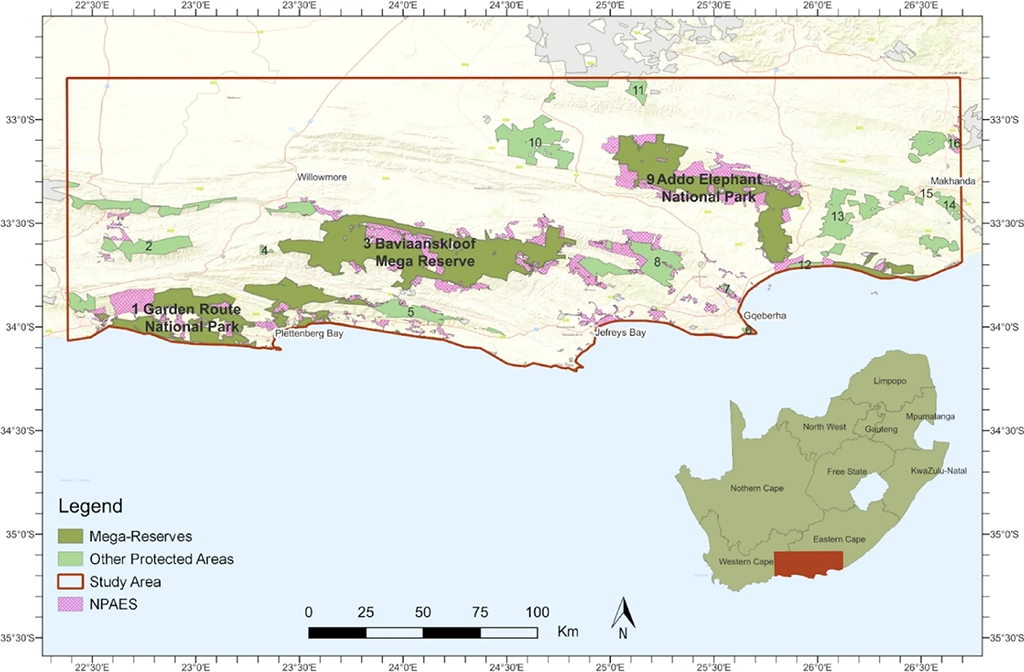

In South Africa’s Cape region, conservationists have long dreamed of linking three of the country’s wilderness areas through wildlife corridors. Through this plan, the Garden Route National Park, the Baviaanskloof Mega-Reserve, and the Addo Elephant National Park would be linked in one continuous landscape. Together, these protected areas form the heart of the Eden to Addo Corridor Initiative, a vision to reconnect fragmented habitats and restore the free movement of wildlife across the mountains, valleys, and plains of the Eastern and Western Cape.

Some of the focus areas for the corridor include the Robberg Coastal Corridor, the Keurbooms Corridor, the Langkloof Corridor and the Springbokvlakte Corridor.

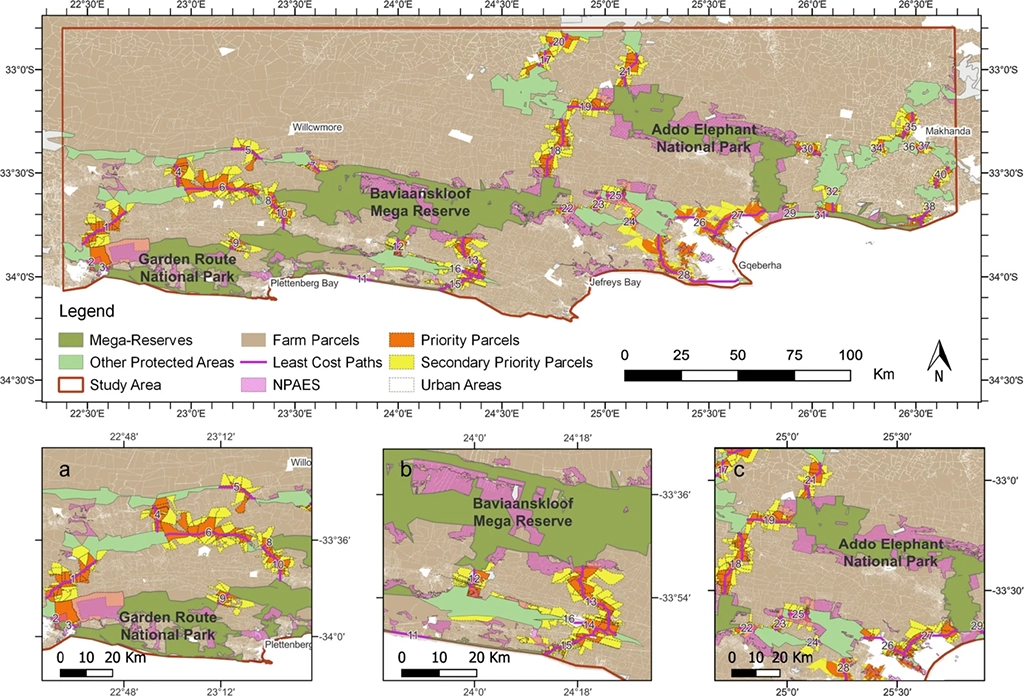

A new study by Daan Lichtenberg and colleagues offers the most detailed map yet of how this could work. Using ecological modelling and expert knowledge, the researchers identified 40 potential wildlife corridors linking the three “mega-reserves” – a network of natural pathways that could one day turn the corridors into a reality.

The research focuses on mammal-based multi-species corridors, and the authors modelled ecological connectivity between the three protected areas. By integrating expert-derived resistance surfaces for nine representative mammal species, the study also highlighted significant barriers like agriculture and roads.

All three of these reserves are ecologically significant. The Garden Route National Park shelters some of South Africa’s last extensive tracts of indigenous forest, fynbos, and wetlands. The Baviaanskloof World Heritage Site lies inland and is a dramatic, folded landscape, hosting both thicket and mountain fynbos. To the east, Addo Elephant National Park protects a range of habitats, from arid Karoo to coastal dunes and marine areas. It supports one of South Africa’s best-known and intensively studied elephant populations, the largest in the Eastern Cape, and rare and endangered species such as the Cape mountain zebra, leopard, and black rhino.

Why corridors matter

Protected areas are islands of safety in a sea of human activity – but isolation comes at a cost. When animals are confined to small, fenced areas, populations become less resilient, genetic diversity declines, and ancient natural movements that once maintained ecosystems halt. Ecological corridors are the bridges that reconnect these islands, allowing wildlife to move and adapt in the face of threats like habitat loss and climate change.

Biodiversity conservation is increasingly dependent on maintaining landscape connectivity, especially in regions like South Africa that are facing rapid habitat fragmentation due to expanding urbanisation and agriculture. Protected Areas alone are often too small and isolated to offer robust, resilient protection for many mammal species

In 2024, South African National Parks (SANParks) unveiled their Vision 2040 strategy – an initiative that intends to align conservation with shared economic growth “in ways that can tangibly change lives”. The vision includes an ambitious strategy known as “Mega Living Landscapes” through which SANParks hopes to allow surrounding communities to have buy-in for the protected areas in their vicinity. This strategy calls for connecting protected areas through a network of green corridors and buffer zones, restoring the movement of species and ecological processes across vast landscapes. The Eden to Addo initiative (so named as the Garden Route region used to be named “Eden”) is a model of this approach – one that balances the realities of farming, tourism, and rural livelihoods.

Mapping the movement of mammals

To build their models, the researchers focused on nine mammal species that represent a range of ecological roles – from browsers and grazers to predators and water-dependent species. These included elephants, leopards, Cape mountain zebras, bushpigs, Cape grysboks, chacma baboons, greater kudus, bat-eared foxes, and Cape clawless otters. Each plays a distinct role in the ecosystem, from shaping vegetation and dispersing seeds to keeping prey populations in check.

The results show a network of 40 potential corridors, most (75%) under 15 kilometres long, that could allow animals to move safely between the mega-reserves. Each corridor was mapped at a minimum width of 2km. The longest corridor extended up to 53.6km. Many follow natural features like forest belts, river valleys, and thicket mosaics, and many also include protected areas neighbouring the focus reserves. Others pass through farmland and private properties, highlighting the crucial role that landowners and communities will play in making these connections work.

The researchers found that most of the proposed corridors lie in areas with a low to moderate human footprint, dominated by natural forest, fynbos, and grassland. However, agriculture and roads remain major barriers – especially near urban centres such as Gqeberha. Still, the research shows that with cooperation and careful planning, connectivity between these parks is within reach.

Beyond the maps

Creating ecological corridors is not just a technical exercise – it’s a social and economic challenge too. The success of the Eden to Addo vision will depend on collaboration between conservationists, farmers, and local communities. Fencing, land ownership, and human-wildlife conflict are real obstacles. But with incentives like biodiversity stewardship, restoration-based agriculture, and carbon credit schemes, connectivity can become part of a sustainable future for both people and wildlife.

This region’s diversity is extraordinary: seven of South Africa’s nine biomes meet here. Reconnecting these ecosystems would help species move and adapt as the climate changes, restore natural processes like fire and migration, and secure long-term refuges for threatened species. For the Cape mountain zebra, which depends on open, connected habitats, corridors could mean the difference between genetic diversity and isolation. For leopards, they offer safe routes between fragmented territories. And for elephants, the corridors reopen ancient pathways once blocked by fences and farmland.

Lessons from the rest of Africa

Similar projects elsewhere on the continent show what’s possible with wildlife corridors. In Kenya, the Mount Kenya–Lewa–Ngare Ndare corridor allows elephants to move safely between mountain forests and the dry savannahs of Laikipia, reducing conflict with people and restoring old migration routes. The Kasigau Wildlife Corridor, linking Tsavo East and Tsavo West National Parks, allows the movement of wildlife between the two national parks.

Further south, the Kavango–Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA), spanning Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, is the largest land-based transfrontier conservation area in the world. Its network of cross-border corridors enables the free movement of elephants, lions, wild dogs, and countless other species across more than half a million square kilometres. KAZA shows that connectivity can be achieved at scale when neighbouring countries and communities share a vision for living landscapes that work for both people and nature.

These examples show how corridors can facilitate migration, coexistence and resilience. The Eden to Addo Corridor could become South Africa’s own contribution to this continental movement, linking its forests, thickets, and plains into one functioning ecosystem where wildlife can once again roam freely.

Want to visit the Cape region on an African safari? Check out our Cape safaris here. Or, browse our other African safari ideas here.

Final thoughts

This study successfully provides a robust, structured framework for multi-species corridor planning, offering crucial insights for conservation practitioners working to enhance landscape connectivity towards regional and national biodiversity conservation goals.

This kind of research gives the Mega Living Landscapes strategy a scientific foundation, showing exactly where ecological corridors can restore wildlife movement between protected areas. It turns a broad conservation vision into practical, data-driven guidance for connecting ecosystems while supporting the people who live alongside them.

However, the authors acknowledge that significant challenges remain, including the need for financial feasibility and engaging landowners, particularly since conservation initiatives often take place on privately owned land. Furthermore, social factors, such as potential human-wildlife conflict (e.g., resistance towards leopards and elephants) and the management of physical barriers like fences, must be addressed at the local level for the long-term sustainability of these corridors.

Reference

Lichtenberg D., Kreuzberg E., von Dürckheim K., et al. (2025). Landscape connectivity for biodiversity conservation: a mammal-based multi-species corridor approach for the Eden to Addo Corridor Initiative, South Africa. Biodiversity and Conservation, 34, 3933–3953. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-025-03140-8

Further reading

- From relaxed elephants to hard-working dung beetles, Addo Elephant National Park is a conservation marvel packed with wildlife, adventure, and history. Read more about Addo here.

- The Cape safari experience: fascinating wildlife and malaria-free protected spaces close to Cape Town and the Garden Route. Check out all the Cape has to offer here.

- The Garden Route is a dramatic meeting of mountains, gorges, forest and the Indian Ocean, interspersed by quaint, sleepy beach towns. Read more about the Garden Route here.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()