European rollers are a flagship species for migratory birds. But their population has declined by more than 30% in 15 years. New efforts to save these rollers – and their migratory paths – will benefit a wide variety of species

European rollers are a flagship species for migratory birds. But their population has declined by more than 30% in 15 years. New efforts to save these rollers – and their migratory paths – will benefit a wide variety of species

Last year, there was a cold snap in the Highveld of South Africa, and during this time, the public reported a sad phenomenon – a high number of deaths of a small, blue-coloured bird, the European roller (Coracias garrulus). Conservationists are not sure why this happened, but these migratory birds probably arrived in South Africa, hungry and tired, after their journey of over 10,000km from European and Asian breeding sites. The cold spell that greeted their arrival would have limited the availability of aerial insects, which European rollers rely on as a primary food source. Equally concerning, sightings of the European roller in the greater Kruger region have dropped. Could this be due to the presence of El Niño conditions in the sub-Saharan countries, which the roller flies through on its way to the dry, wooded savannah plains of South Africa? These dry conditions might have meant these feathered travellers could not sufficiently refuel during their journey. Conservationists are worried: where are these birds? Are they stopping off in other countries now to reduce their journey time? Have they encountered the wrong end of a rifle in countries which practice bird-hunting?

Birdlife South Africa has started a conservation programme to find answers to these questions, as well as others, about the European roller and its worrying decline in some countries. Although it was downlisted from ‘near threatened’ to ‘least concern’ in 2015, there are indications that its populations are in decline. In Europe, between 1990 and 2000, the European roller population declined by 25%; in Poland, only 30 pairs remain. The question hovers – if this is the European roller, isn’t this the Europeans’ problem? Not so – migratory species require conservation measures across their range, as what happens in one country has ramifications for the population dynamics in the other countries through which the rollers roll. It defeats the purpose of spending many resources to create protected areas in one country but not protect the species on its flyway (migratory flight path) through Africa and Europe. The migration chain is only as strong as its weakest link. Without every link being secure, these turquoise twitterers will eventually be no more to protect.

The concept of conserving flyways has taken off in the conservation sector. A flyway is the entire range of a migratory bird species (or groups of related species or distinct populations of a single species) through which it moves on an annual basis – from breeding grounds to non-breeding areas, including intermediate resting and feeding places as well as the area within which the birds migrate. The European roller has a new role – a flagship for the EAFI (East Africa Flyway Initiative). Many species migrate along broadly similar, well-established routes, and as the European roller uses the East Africa flyway, taking measures to protect the flyway for rollers is likely to protect the other species that use this flyway, too.

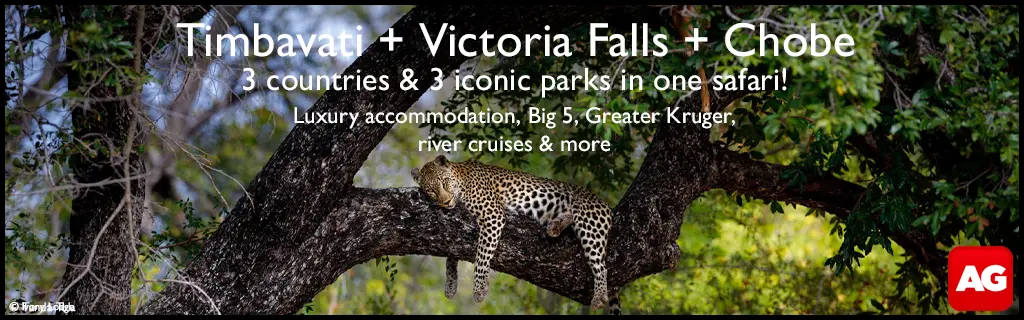

Want to see European rollers while on safari in Africa? Check out our selection of ready-made safaris here, or let our travel experts plan the perfect African safari for you by clicking here

Want to see European rollers while on safari in Africa? Check out our selection of ready-made safaris here, or let our travel experts plan the perfect African safari for you by clicking here

The European roller faces different threats across different countries. In Europe, increasing land-use change for agriculture has left large parts of the countryside treeless, thus reducing breeding habitat for this tree-nesting species. Worse still, the birds have to run the gamut of being shot, trapped or poisoned in some areas in the Mediterranean, Northern Europe and the Caucasus. Habitat loss and pollution are also significant threats, and as for climate change, this is a severe concern for species that fly across continents to track resources. What happens if insects emerge earlier? What happens if the seasons stay colder for longer?

To counteract these threats, conservationists need to know more. This means they need to identify the habitat requirements of the roller in Africa and Europe and along the migration route it uses. The only way to know where they go is to track them. So, in March 2024, the Birdlife South Africa team tagged two European roller individuals with tiny satellite trackers. This costly solar-powered technology has the potential to be a game changer in understanding how birds use their flyways and where conservation efforts should be prioritised. The tags have already shown the Birdlife team that one of their rollers covered 2,000km in just 4 days! The team are holding their breath that the tags work for their entire expected lifespan and that nothing happens to the tagged birds during this time. Ideally, they need more tags to capture the variety of birds’ choices during their epic travels.

Blood samples were also taken while fixing the tags for the birds. This is because the European roller has two recognised subspecies, both of which occur within its overwintering sites in southern Africa, namely C. g. garrulus (from the Western Palearctic) and the C. g. semenowi (from western and central Asia). To gather data on the population trends of these subspecies, it is first necessary to identify the different subspecies (and the different colouration between the subspecies is not always distinct) and then track their different migration routes.

The Birdlife team has also started a monitoring programme. By ringing 50 European rollers with special, easily identifiable rings, they hope to understand how the population changes over time. This method relies on regular checks by dedicated volunteers and ad hoc reporting from the general public. So, if you spot a roller sporting a nifty, shiny ring on its leg, do not hesitate to report this sighting to Birdlife (see contact details at the end of the article). Sightings are essential data points, so your participation is critical to the success of this programme. The monitoring is currently taking place in Kruger National Park, two private nature reserves in KwaZulu-Natal and several additional reserves across South Africa.

Besides tracking the birds’ progress across thousands of kilometers, the conservationists intend to work with partners in all the countries in the flyway. This is the magic of migratory bird species – they have the potential to catalyse collaborative conservation across borders and boundaries. The fate of this iconic blue bird is hanging in the balance, along with many other birds that use these flyways, including waterbirds.

We all have a role to play in helping the roller get to where it’s going. If you want to know more about how you can make a difference, learn more about Birdlife’s project here. You can also contact Jessica Wilmot, from Birdlife South Africa’s European Roller Monitoring Project.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()