EDITORIAL NOTE: A recent report compiled by investigative journalists and publicised by a Daily Maverick article has slated Namibia’s much-vaunted community-based wildlife conservation program. This has incensed a significant portion of the Namibian conservation community. 76 entities/people have responded by way of three separate posts below – correcting factual inaccuracies of the report and questioning the motives of the journalists. To better understand the situation, please read the above links and the three responses below. The list of compilers appears below each response.

Summary of allegations made in the three responses below:

- There are factual inaccuracies in the report, as detailed below

- The critical report, while purporting to convey concern for people and wildlife, is based on a thinly veiled anti-hunting agenda

- The Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) has never been touted as a silver-bullet solution to Namibia’s socio-economic challenges yet is blamed for several external factors that have little to do with the CBNRM programme itself

- There is no evidence that the interview “data” was gathered with the necessary permits and ethical clearance. To conduct fieldwork and social research without permits is illegal in Namibia. The methodology and scientific rigour of the report are severely wanting

- There is no mention of obtaining free, prior, and informed consent from interviewees. Some of the individuals interviewed have later claimed that their responses were misrepresented or distorted to suit the report’s conclusions. In essence, the investigative process was conducted in bad faith

- There appear to be conflicts of interest regarding the research funding and personal biases of the journalists

- The report uses disingenuous comparisons to analyse and compare hunting revenue data to that generated by other forms of non-consumptive tourism

- The report cherry-picks the challenges facing specific areas, focusing on wildlife declines in regions severely affected by drought, and socioeconomic issues in areas where wildlife populations are healthy and thriving

- Conclusions regarding wildlife populations and human-wildlife conflict (particularly concerning elephants) appear to have been based on drive-by observations over a few weeks rather than substantive scientific data produced by previous studies over a more extended period

- While the difficulties faced by rural Namibians highlighted in the report are accurate, the report inaccurately extends the blame to the CBNRM and, in many instances, fails to include vital context that might otherwise contradict the author’s conclusions

Response 1: Why false sympathy will not help Namibian people or elephants

Animal rights organisations seem to be strangely fixated on Namibia’s community conservation model. The reason for this fixation is obvious – Namibia includes hunting as part of its broader wildlife economy and has made greater efforts to include rural communities in conservation than most other countries in the world. Recently rated second in the world for conserving megafauna (i.e. large mammals) in a peer-reviewed scientific paper, Namibia’s strategy that includes the sustainable use of wildlife is clearly working, much to the annoyance of animal rights organisations.

It, therefore, came as no surprise when a coterie of such organisations – Animal Survival International, Animal Welfare Institute, Born Free Foundation, Fondation Frans Weber, Future for Elephants, Humane Society International and Pro Wildlife – funded this report on Namibian conservation, despite none of these organisations funding any real conservation work in the country. Since animal rights positions are effectively countered by the success of human rights-based conservation, they specifically targeted the Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) programme.

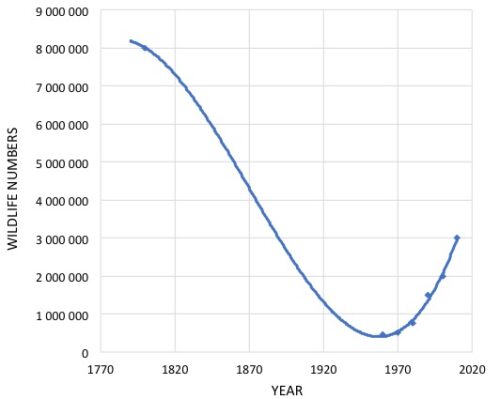

CBNRM was established in southern Africa during the 1980s and 1990s when several newly independent countries were looking for more inclusive conservation models than those practised by the colonial regimes. In Namibia, one of the major issues identified by rural communities was the discrepancy between wildlife ownership on freehold land (then held exclusively by white farmers) compared with communal land. While freehold farmers were granted rights to use wildlife occurring on their land a few decades before independence (leading to impressive wildlife recoveries on these lands), people on communal lands were still locked out of the wildlife economy. With no incentive to conserve wildlife perceived as belonging to the government and white people only, poaching was rife, and the human-wildlife conflict went unchecked, making some communities openly hostile towards conservation officials.

That all changed with an amendment to legislation in 1996, which allowed self-identified communities to apply for their lands to be gazetted as communal conservancies that they would manage following their own constitutions. This opened the door for people on communal lands to obtain similar rights to wildlife as freehold farmers, which soon resulted in wildlife populations increasing on land where it was formerly pushed to the brink of local extinction.

In practice, operating a communal conservancy is a complicated task, as these groups of people choose to work together to conserve their resources for the common benefit. Further, the wildlife species that live on these lands are notoriously difficult to live with – elephant, lion, crocodile and hippopotamus occasionally take human lives, while these and other species (e.g. spotted hyaena, leopard, cheetah and African wild dog) frequently threaten livelihoods by destroying crops and killing livestock. Furthermore, communal conservancies are unfenced, which on the one hand makes them particularly useful as wildlife corridors but on the other introduces the difficulty of keeping unwanted visitors or illegal settlers out. Finally, these community institutions are nested within a larger socio-economic and ecological landscape that inevitably affects their operations and members’ lives.

Journalists Adam Cruise and Izzy Sasada use the complexity of CBNRM and broader societal issues that have little or nothing to do with CBNRM to create a thin veil of feigned concern for people and wildlife that does little to conceal their primary objective – to attack trophy hunting. Cruise is on record comparing the sustainable use of wildlife for the benefit of people to parasitism, where humans are the ‘parasite’ and nature is the ‘victim’. Their report would never pass any form of peer review due to its almost information-free methods section. Besides that, there are apparent conflicts of interest relating to funding, and the lead author has previously expressed extreme bias against the object of investigation – African communities using their natural resources for their benefit.

Regarding the methodology, nothing is said of the total interview sample size, how interviewees were selected or what kind of questions they were asked. Furthermore, there is no mention of obtaining free, prior and informed consent from interviewees or of any ethical clearance or research permits received prior to this fieldwork. Omissions of this nature are not permitted in scientific literature because they are easily used to hide interviewer bias and unethical procedures. By publishing this report without any of the relevant information described above, the interviewers effectively sidestepped all ethical requirements or the need for scientific rigour. In order to work in Namibia, foreigners must apply for permits from the Ministry of Home Affairs and Immigration, while research permits must be obtained from the National Commission on Research, Science and Technology. Conducting fieldwork and social research without such permits is illegal in Namibia.

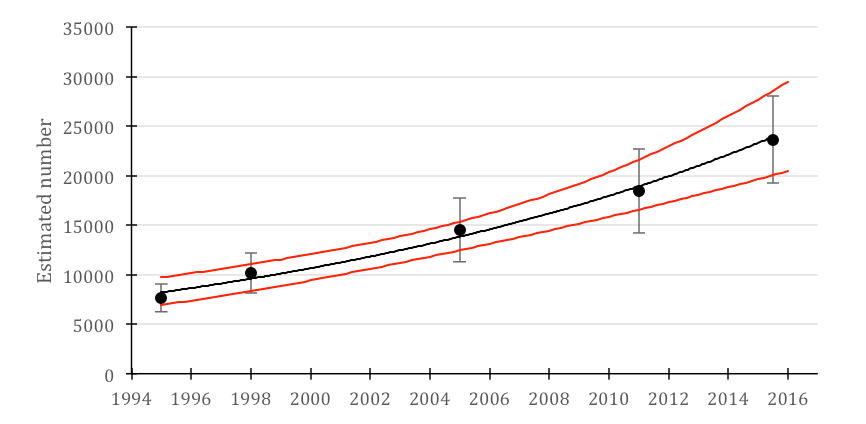

Meanwhile, the “on-site assessment” of issues relating to elephants appears to have been based on drive-by observations lasting a few weeks in each of the regions they investigated. These random observations are then used throughout the report to cast doubt on data collected through well-established scientific methods (e.g. aerial surveys), extensive government consultations regarding human-elephant conflict, and long-term data collected by the conservancies. Elephant sightings from the ground, gathered without systematic methodology, inevitably underestimate elephant population numbers, which is why aerial surveys (and counts of individually identifiable elephants, where possible) are used to generate more accurate estimates in Namibia and elsewhere in Africa. Yet Cruise emphasises casual drive-by observations or elephant sightings recorded by the conservancies from ground-based counts, thus implying that these are more accurate than systematically collected data.

Cruise and Sasada’s initial description of the economic benefits of trophy hunting is a telling glimpse of the bias that runs throughout the report. Comparing the contribution to the GDP from a niche sub-sector of tourism that requires free-roaming large mammals (i.e. hunting) with that of tourism, in general, is disingenuous. The entire tourism industry includes hotels, beach resorts, scenic tours, etc., which does not require any wildlife to be present; most of this tourism revenue accrues to urban areas. Dividing hunting income by land surface area is even more bizarre, especially for a vast desert country such as Namibia – hunting income is not used to cover every hectare of the country in money.

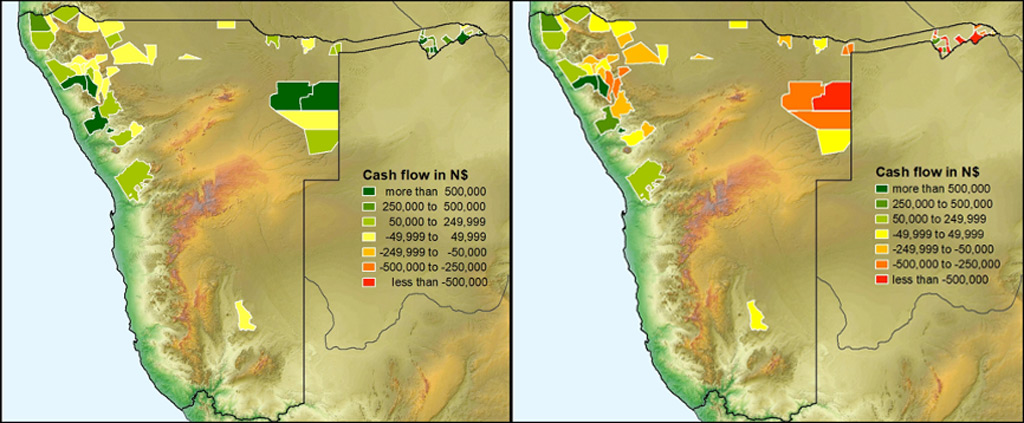

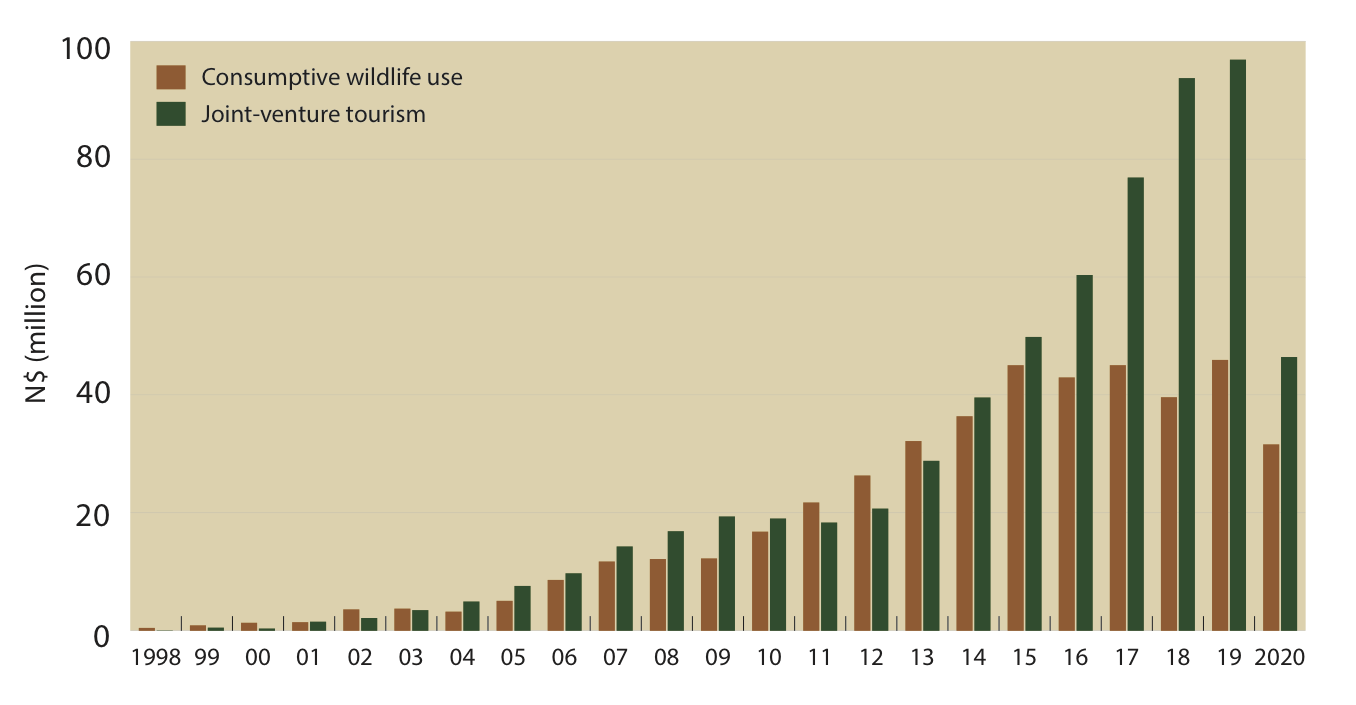

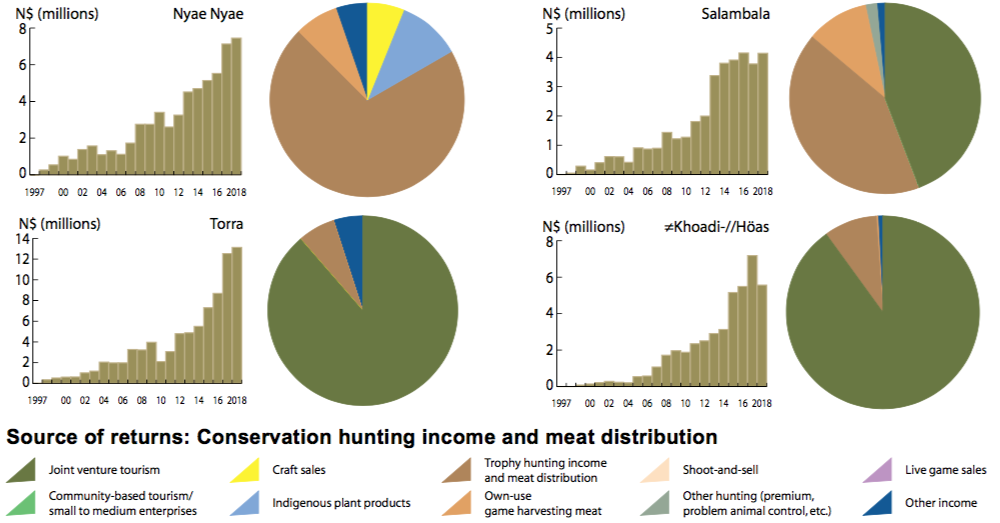

More relevant statistics that focus on the relative contributions of these two industries to communal conservancies reveal that hunting (which includes trophy and meat hunting) contributed 30% of the total revenues generated by communal conservancies. In contrast, tourism contributed 66% in 2019. Additionally, many conservancies rely solely on revenue generated through hunting for their income.

The authors’ other biases are visible in their treatment of conservancies located in three different regions of the country – Kunene, Otjozondjupa and Zambezi. In the Kunene Region, which has suffered a severe, prolonged drought in recent years, the focus is on wildlife declines. Drought is the ultimate cause behind the wildlife declines and the increased poverty reported among Himba people (who lost most of their livestock due to drought), yet it is barely mentioned.

Cruise, the journalist who tackled the “elephant ecology” part of the report, fails to explain that wildlife migrates extensively and/or die-off during times of drought, only to return and reproduce quickly when conditions are favourable. Therefore, his random observations at the end of a long drought period are not an accurate portrayal of wildlife trends since the start of CBNRM (these trends are publicly available here). He also appears to be unaware that these arid areas are at the extreme margin of elephant range (even without conflict with people), making this sub-population particularly vulnerable to drought. This situation further exacerbates conflict with farmers, which led to the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT) taking steps to reduce elephant numbers in the eastern parts of the Kunene Region through a live elephant auction.

In eastern Otjozondjupa, where elephant populations are healthy and increasing, Cruise and Sasada shift the focus from wildlife management to marginalised rural communities. Like other journalists who have dropped in to interview these communities with false sympathy for their plight, they present the many socio-economic challenges San people face today, most of which have little or nothing to do with CBNRM. Everything from alcoholism to the price of food at local shops is described in detail, while even conservancies are cast as some form of oppression.

The uninformed reader might be led to believe (deliberately, it seems) that the government appoints committees to manage these conservancies, yet this is not true. Conservancy management committees are elected by their own communities following democratic processes. One of the CBNRM-related complaints from this region was the inequitable distribution of meat – interviewees clearly wanted more meat more frequently. One wonders if the interviewer revealed that their ultimate goal was to cut off the game meat supply to these communities entirely?

The third region – the Zambezi (formerly Caprivi) – also has healthy wildlife populations. The journalists quote fewer people in this section compared with the other areas (which leaves open the possibility that most of the responses they received were not to their liking). They, therefore, shift their focus once more to include the failed secession attempt by some Caprivians in 1999 (what that has to do with CBNRM remains unclear), plus human-elephant conflict that is a real challenge in an environment where both human and elephant densities are high. The Zambezi Region is home to over 90,000 people and is located in the centre of the larger Kavango-Zambezi Trans-frontier Conservation Area that supports an estimated 220,000 elephants.

A common complaint reported both here and in the other regions was that not enough money is provided through the government’s conflict offset scheme (which is topped up by conservancies). What Cruise and Sasada fail to mention to their readers is that the current scheme would not exist without funds generated from the sustainable use of wildlife (via the Game Products Trust Fund). What they failed to mention to their interviewees is even more egregious – that their ultimate desire is to eliminate the current source of funding for human-wildlife conflict offsets entirely.

Taken as a whole, this report looks distinctly like a “hit-and-run” job aimed at trophy hunting, with community conservation as a secondary casualty. Now that the interviews are over, perhaps the authors would like to return to Namibia to present their results to their interviewees – with honest conclusions and detailed consequences of their recommendations. A fair presentation would include the following points:

- You (interviewees) wanted more meat and other benefits from your conservancy; we want your conservancy to stop the sustainable use of wildlife, which means there will be no more meat to distribute, while other benefits will similarly decline in future.

- You desired more money to offset the costs of living with wildlife; we want the current source of funding (i.e. sustainable wildlife use) for the offset scheme to be eliminated, thus leaving you with no offset scheme at all.

- You complained about people who come in from outside and settle on your land illegally; we would like to weaken further the grassroots institutions in your region (conservancies) that have fought legal battles for your cause.

Unfortunately, expecting such an honest report is unrealistic since the whole investigative process was done in bad faith. Having spoken to an interviewee quoted in this report, we know that the journalists did not introduce themselves as such and obtained no consent whatsoever to use any of the quotes they obtained. Indeed, this interviewee recalls giving a very different response to the one that is attributed to her in this report. The people who provided their honest, off-hand opinions to a passing stranger would have had no idea that their words would be twisted and used against them – to worsen their current situation.

The journalists and their financiers will no doubt use this illegal and unethical report to further their animal rights agenda while not spending a dollar of their lobbying budgets to alleviate the plight of the people left in their wake. In fact, a worse situation for both people and animals would prevail if their dream of dismantling community conservation came true. Over 1,000 people who are directly employed by conservancies will lose their jobs, the meat currently being distributed will no longer be available, and the voices of marginalised rural communities will be silenced. For the animals, poaching and the associated illegal wildlife trade will skyrocket in the absence of community game guards. Unchecked human-wildlife conflict will result in more deaths (of wild animals, livestock and people), and the wildlife corridors in the Zambezi Region will be effectively closed by agriculture.

The difficulties faced by rural Namibians and reflected in this report are real, yet CBNRM has never been presented as the silver bullet that would fix every problem in society. As it stands, this democratic system of wildlife management is not perfect, and solutions to the multiple challenges that conservancies face are far from simple. If COVID-19 has taught us anything, however, it is that everything becomes much more difficult when income from wildlife-based industries is summarily cut off. The ultimate goal of this report – to effectively remove 30% of all conservancy revenues and 100% of revenues for hunting-reliant conservancies – should therefore be treated like a viral infection that would significantly weaken Namibia’s conservation efforts.

The following institutions and people supported the above response:

Response 2: We will not be bullied

The report by Adam Cruise and Izzy Sasada on the Namibian Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) programme is based on highly unethical and illegally conducted research, the results of which were twisted to suit their agenda. This pair of journalists entered our conservancies and spoke to people without obtaining a research permit from the government or even informing our conservancy offices of their intentions. Those of us who recall speaking to them and are quoted in their report were misrepresented, as our statements were taken out of context and used to tell an untrue story about Namibia.

As representatives of Namibian conservancies, we hereby condemn both the methods and the outcome of Cruise and Sasada’s report in the strongest possible terms. The authors and the organisations that financed this research have broken Namibian laws and shown extreme disrespect for Namibian people and their rights.

CBNRM is a critical mechanism for linking nature conservation with rural livelihoods and development needs. We, therefore, resent the deliberate use of the challenges we face – including widespread poverty, terrible drought conditions and human-wildlife conflict – as a means of dismissing our conservation efforts. We are the custodians of the last free-ranging black rhino population on earth; we live among dangerous wild animals that have been eradicated elsewhere, and we zone significant portions of our land for wildlife conservation. Yet, in this report and others driven by the same agenda, we are unfairly judged and punished – for the sole reason that we defend our right to the sustainable use of wildlife.

The challenges associated with rural development and poverty alleviation in Africa are not limited to Namibia. Yet, our progressive constitution and flagship CBNRM programme have included wildlife conservation within our development goals. Many countries in the developed world like to talk about Sustainable Development Goals. In Namibia, we live Sustainable Development. From first-hand experience, we can tell you that it is not easy balancing our people’s current, urgent needs with our desire to protect wildlife for future generations. Especially when that wildlife includes dangerous wild animals like elephants that trample our crops, destroy our water points, and even threaten our lives.

The Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT) and the support organisations that fall under the auspices of the Namibian Association of CBNRM Support Organisations (NACSO) are trusted partners who assist us with overcoming these challenges. By contrast, none of the animal rights organisations that funded Cruise and Sasada’s report has ever provided any assistance towards conserving elephants or other wildlife in Namibia. They, therefore, have no right to criticise our conservation efforts or undermine our financial viability. Furthermore, without our active participation in anti-poaching patrols, human-wildlife conflict mitigation, and awareness creation within our respective communities, there would be no wildlife on communal lands in Namibia. Yet, the eradication of wildlife appears to be a desirable outcome for Cruise and Sasada and the organisations that funded their illegal activities.

Many of the social problems highlighted in their report are beyond the scope of communal conservancies or beyond our ability to control. Nonetheless, as community-based institutions, we have an essential role to play in bringing our members’ concerns to the attention of government and other stakeholders. While we cannot eliminate all social problems on our own, we aim to use the limited budgets we have to create tangible benefits for our communities. Cruise and Sasada dismiss these benefits as being unworthy of consideration, yet they do not offer alternative or better forms of income that we could use to increase member benefits. It is clear that they have no interest in improving the lives of the people they interviewed but rather seek to impoverish them further.

While in Namibia, Cruise and Sasada used trickery and deceit to obtain their interviews. Having stolen our words without our consent, they are using their report to bully us into submission. But we will stand by our goal of sustainable rural development; we are proud of our conservation achievements. We remain the rightful custodians of free-ranging wildlife on communal lands, and we will continue to expand our natural resource-based industries to increase benefit flows to our members. African people have been denigrated, misused and misrepresented for far too long for us to accept more of this appalling treatment at the hand of foreigners. We will not be bullied.

The following people signed the above response:

Max Muyemburuko (Chairperson of the Kavango East- and West- Regional Conservancy and Community Forest Association + Stein Katupa (Secretary-General of the Kunene Regional Community Conservancy Association) + Brisetha Hendricks (Chairperson of the Kunene South Conservancy Association) + Wesam Albius (Chairperson for the Zambezi Chairperson Forum) + Gerrie Ciqae Cwi (Chairperson of the Nyae Nyae Conservancy) + Visser N!aici (Chairperson of the N#a Jaqna Conservancy)

Response 3: Setting the record straight

≠Khoadi //Hôas Conservancy recently featured in a report by Adam Cruise and Izzy Sasada that sought to undermine Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) in Namibia. We strenuously object to the way in which our conservancy was portrayed and wish to correct the many errors and misleading statements made in this report. These individuals came into our conservancy without informing us of the true purpose of their activities, and although one of them (Sasada) claimed to be doing ‘research’ on human-wildlife conflict, no research permit was presented.

The reporters deliberately distorted a casual conversation (not a formal interview) they had with our conservancy manager, Ms Lorna Dax, which leads us to believe that most if not all of the people they quote in their report were similarly misrepresented. In this conversation, Ms Dax responded to questions about the income generated by ≠Khoadi //Hôas Conservancy, saying that most of the revenue came from tourism, while hunting was a second important source of revenue. This is not a secret since Grootberg Lodge is well known as our primary source of income in normal years (COVID-19 significantly reduced international visitor numbers).

In their report, Cruise and Sasada distort this simple statement by saying that Ms Dax implied that hunting generated little or no income for the conservancy. They support this distortion by misusing statistics presented in the 2019 audit report for our conservancy that is kept on the Namibian Association of CBNRM Support Organisation’s (NACSO) website. This information is presented on a public website in the interests of transparency, yet it was misinterpreted (deliberately or otherwise) by Cruise and Sasada.

The audit report they refer to quotes “Potential Trophy Value” figures for each of the species that we have on our quota, with a note stating that these are average figures that are not indicative of actual income to the conservancy (which is based on a contract with the hunter that includes more than just the trophy fee). They use these figures to claim that ≠Khoadi //Hôas Conservancy generated N$ 45,000 from trophy hunting in 2019, which represented 34% of our total income for that period. For the 2019/20 financial year (running June to May), the actual amount was N$ 783,232 – over 17 times higher than their figure.

Had the reporters formally requested information from our conservancy office and provided us with a full explanation of their reasons for using this information, we could have provided the correct data. However, they would not have succeeded in their goal using an honest approach since their research was illegal, and their ultimate purpose was to discredit our conservancy.

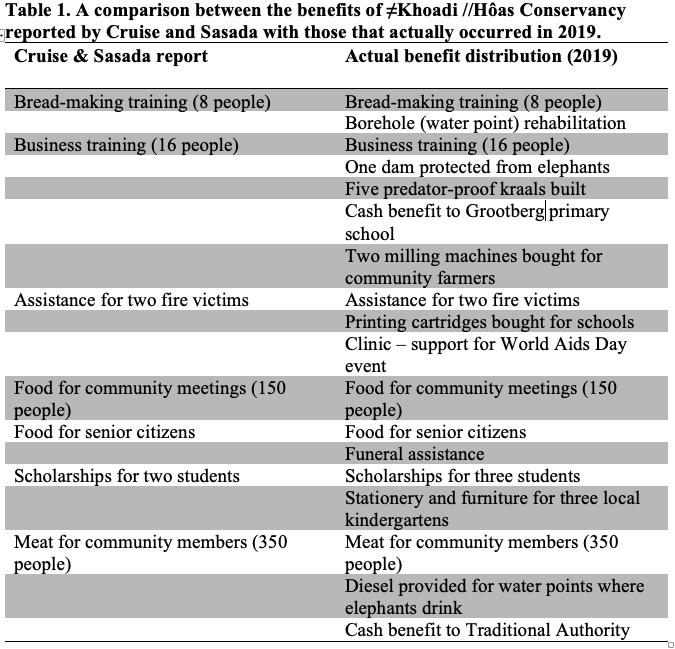

Their report on benefit distribution among our members is also misleading, which must be deliberate since this information is contained in the 2019 audit report that they quote. Cruise and Sasada only list 7 of the 18 benefit categories that we recorded in 2019 (Table 1).

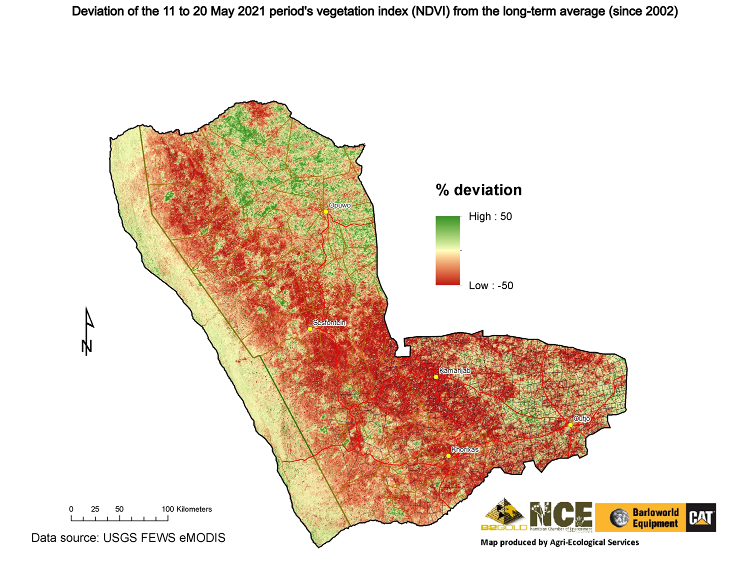

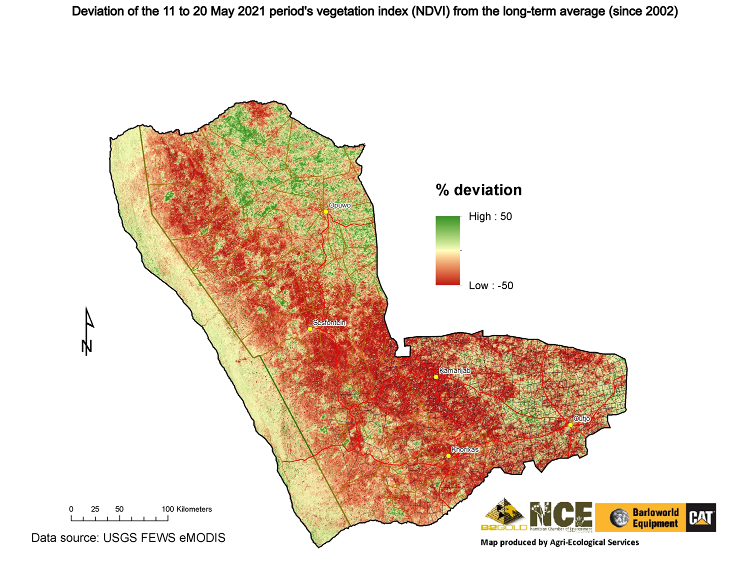

Cruise and Sasada further misrepresent the state of our wildlife populations. Our conservancy and our neighbours in the Kunene Region have experienced a severe drought since the last good rains fell in 2011. By the time these reporters visited us in May 2021, we had endured ten years of below-average rainfall, during which time many livestock have died, and wildlife migrated to areas that had more grazing. This desperate situation was further compounded by loss of income since the outbreak of COVID-19 in March 2021. We cannot control the climate (which is getting worse due to climate change) or prevent the outbreak of a global pandemic. Yet, Cruise and Sasada blame communal conservancies for problems created by these external forces. This is simply unjust.

Human-elephant conflict remains one of our biggest challenges. We work with our farmers to provide water for elephants and prevent the destruction of critical water points. Our environmental shepherds (known elsewhere as game guards) have kept records of these problems for many years, and elephants are a frequent subject of debate at our community meetings. Yet, according to “a pair of goat herders” that Cruise and Sasada happened to meet while conducting their illegal research, elephants are ‘not a problem’. We do not even know if these herders are long-term residents of our conservancy – many people come in for emergency grazing purposes that are not residents or members. How would they know about the long-term struggles with elephants across our whole conservancy?

Other basic errors in their report were the number of people in our Conservancy Management Committee – there are 15 (9 men, 6 women), not as they report 17 (14 men, 3 women). We employ 9 environmental shepherds and not 7 as they report. They claim that 6.4% of our revenues are spent on community benefits, yet the actual benefit proportion for our 2019/20 financial year was 27%. This excludes the salaries paid to our staff (who are also community members) that constituted a further 24% of our budget. The authors speak of the number of jobs created by our conservancy with disdain, yet if we employed more people, there would be less money available for broader community benefits. We simply cannot employ every member of our conservancy, which is a false expectation. The jobs we do create nonetheless support several families and are linked directly to the conservation of wildlife.

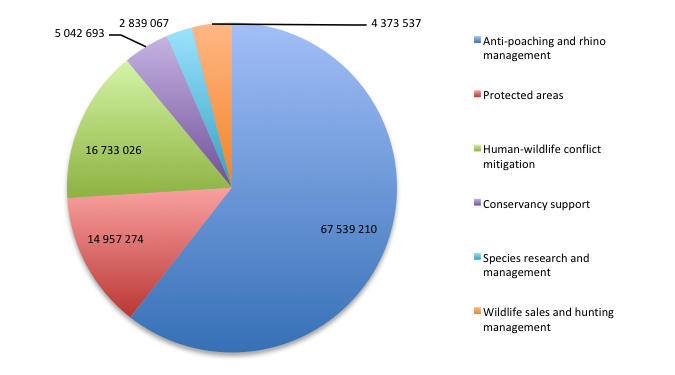

Our operating costs, which accounted for the remaining half of the budget in 2020, include essential activities such as anti-poaching patrols, human-wildlife conflict mitigation projects, game counts and other wildlife monitoring activities, vehicle running costs (including to distribute benefits) and meetings to ensure good governance. Without these activities, the conservancy would not be able to conserve wildlife or run our affairs effectively.

In their report about our conservancy and others in Namibia, Cruise and Sasada use poverty, lack of sufficient benefits and funds for conflict mitigation as reasons to attack CBNRM. Yet, they also want to prevent us from generating revenue through sustainable wildlife use. It is clear to us that the authors of this report and the organisations that funded this investigation do not have the best interests of our communities at heart. Our community democratically elected our conservancy committee to govern the conservancy while our employees work for our people. Our members are our family and friends; we suffer with them when they suffer. We do not need outsiders who barely understand what CBNRM means and who clearly prefer animal rights over human rights to tell us how to conserve our wildlife or provide for our community.

The following people signed the above response:

Asser Ndjitezeua (Chairman, ≠Khoadi //Hôas Conservancy) + Lorna Dax (Manager, ≠Khoadi //Hôas Conservancy

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()