Before the year 2000, wildlife in Zimbabwe was thriving, partly due to the role played by private landowners such as commercial farmers. Private land was home to important populations of endangered species, including 80% of Zimbabwe’s cheetahs and other carnivores. Zimbabwe was held up as a model for how land can be effectively managed for the benefit of animals and people, and other countries soon adopted their policies and replicated their success. Written by: Dr Sam Williams

However, a fast-track land reform programme was initiated in 2000 in Zimbabwe, resulting in the haphazard resettlement of large numbers of people onto enormous areas of private land. The impacts of this process on people, such as hyperinflation, poverty, and the collapse of the healthcare system, made international headlines. But until now, no one has systematically studied how the wildlife populations were affected.

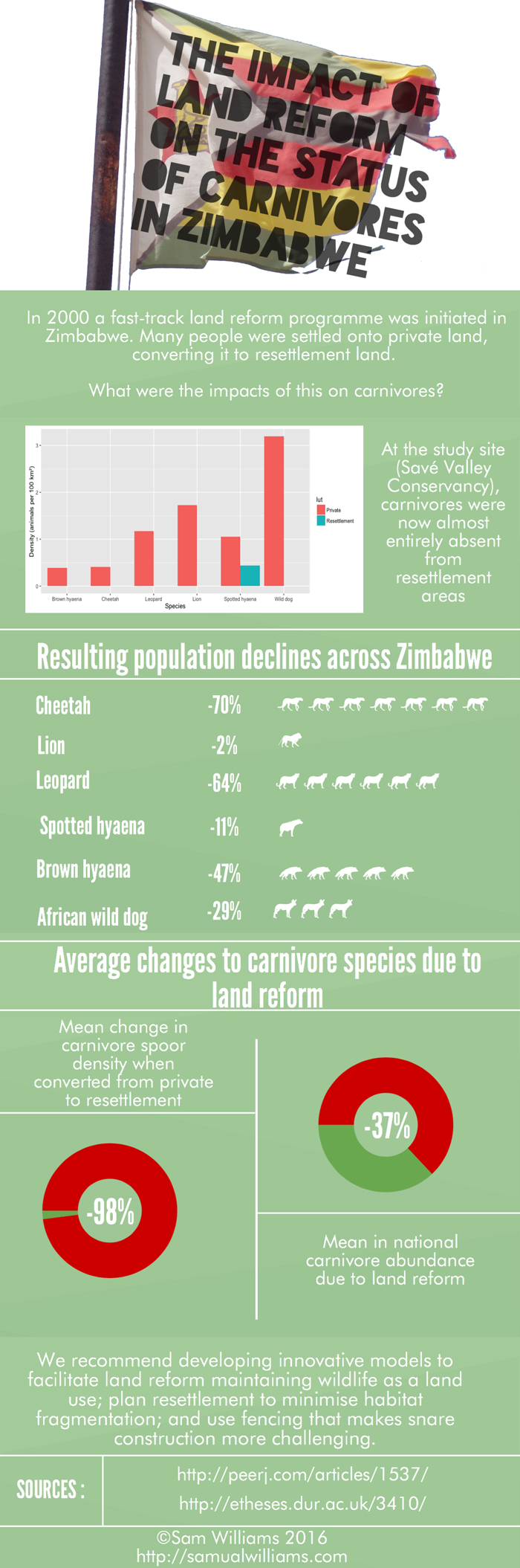

My colleagues and I set out to change this. With the help of experienced trackers, we conducted spoor (footprint) surveys across a thousand kilometres of transects on three land-use types: private land, resettlement land (former private land that had now been resettled), and communal land in Savé Valley Conservancy (SVC) and the surrounding area in south-eastern Zimbabwe. The spoor records allowed us to estimate the abundance of large carnivores in each area.

We focused our analyses on large carnivores, as they are important flagship and keystone species, and our scientific findings were recently published here. On average, the spoor density of carnivores was 98% lower on resettlement land than on private land. When we extrapolate this to a national scale, our tentative findings suggest that the land reform programme has resulted in a decline in the number of large carnivores of up to 70% across the country. Worryingly, we also found that merely being close to resettlement areas was sufficient to cause declines in wildlife abundance on private land. The main driver appears to be industrial levels of poaching.

This is clearly bad news for wildlife but also bad news for people. The declines in wildlife populations could have resulted in the loss of many associated benefits, such as jobs, food security and income. We also conducted hundreds of interviews to assess the level of human-wildlife conflict and found that conflict has spiked. We found that resettlement farmers reported much higher rates of cattle losses to carnivores than farmers in communal areas despite investing more heavily in anti-predator techniques.

Our conclusions are that Zimbabwe’s land reform programme has been catastrophic for wildlife and human-wildlife conflict.

What lessons can we learn from this?

Planning resettlement schemes carefully would be a good start rather than allowing them to occur haphazardly. This would allow resettlement areas to be located in areas of greater agricultural potential while maintaining wildlife populations’ connectivity. We also recommend using fencing wire that cannot easily be used to manufacture snares. When land is resettled, the steel strands commonly used in fence construction are often stolen and used for snaring.

Most importantly, however, we stress that land reform doesn’t have to mean changing land use. Land reform initiatives should maintain wildlife as a land use where it is most appropriate while diversifying the ethnic profile of landowners. Leasing resettled land back to the former owners could benefit wildlife while raising more income for new owners than switching to subsistence farming. Bringing in community members as stakeholders on private land and allowing them to benefit economically from wildlife will also encourage them to protect, rather than poach, animals.

Many potential models for achieving land reform in more productive and sustainable ways exist. By taking this opportunity to develop innovative models of land reform, Zimbabwe could once again become a world leader in managing land for the benefit of wildlife and people.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()