It took me almost three days to get from Italy to Lugonesi village in western Tanzania – and you know you are heading to a really remote area of the country when you are the only mzungu (white person) waiting for the local flight from Dar es Salaam to Tabora!

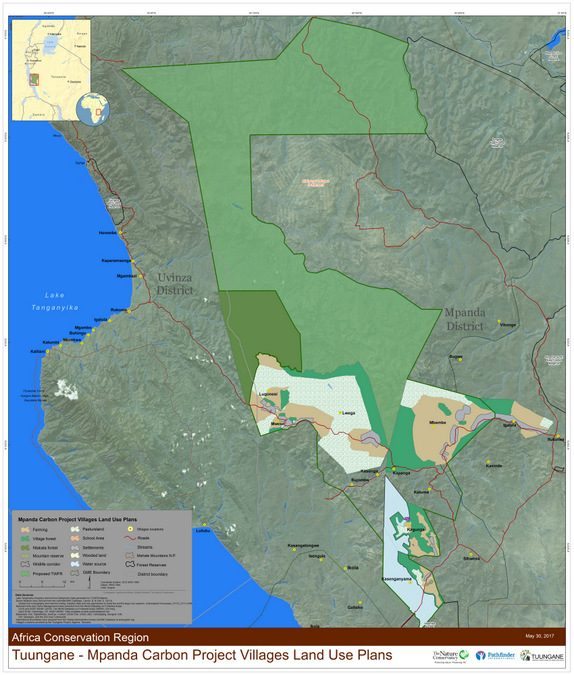

My arrival in Mpanda made the day of some bewildered immigration officers who saw a white lady come out of the Tuungane Project Office. I was here to visit the Carbon Tanzania forest conservation project in Tanganyika District, and Carbon Tanzania’s local partner, Tuungane – a collaboration between The Nature Conservancy and Pathfinder International.

I had just used the toilet but it was enough for them to take me straight to immigration as they were convinced I was looking for a job. They pointed out that on a tourist visa I wasn’t allowed inside a business place, which meant not even restaurants, bars, nor the post office! They were totally puzzled: why should a white person prefer remote south-western Tanzania rather than visiting the Serengeti? So that’s how I ended up in a small room for interrogation. In typical Tanzanian style, I was the one who suggested the questions and helped with the English spelling of my replies. A little glaring, some Law & order-type confessions, my fingerprints all over the documents and after three hours I wasn’t just released, but we had become best friends too: “We forgive you Ms Soresina”.

I have to admit that their doubts made total sense: why should anyone even consider walking in a forest for days, in the heat, carrying all their food and equipment to reach a sample plot for a carbon baseline survey?

What is Carbon Tanzania?

Up until now, I have never been involved in projects that mitigate climate change, however, during my last expedition, I had the opportunity to spend some time exploring the greater Mahale ecosystem and Carbon Tanzania’s newest project site.

Carbon Tanzania is a social enterprise with an innovative approach to habitat conservation based on selling carbon offsets that result from keeping carbon locked up in forest ecosystems. These forests are owned by indigenous communities who earn an income from the sale of these offsets, funds that are then used for community development needs. Global climate change is real and has already had observable effects on the environment. Glaciers have shrunk, ice on rivers and lakes is breaking up earlier, plant and animal ranges have shifted and trees are flowering sooner.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is an important heat-trapping (greenhouse) gas, which is released through human activities such as deforestation and burning fossil fuels, as well as natural processes such as respiration and volcanic eruptions. The forests retain large carbon stocks, and when they are cut down for charcoal production, agriculture or wood extraction, carbon dioxide is released, thereby contributing to global climate change.

By preventing deforestation, which globally contributes to almost a third of all greenhouse gas emissions, communities can earn carbon ‘credits’ which can be sold on the global voluntary carbon market, thereby providing revenue which is used to directly in forest conservation as well as pay for sustainable projects and basic services provided within the villages.

Carbon measuring

To determine how much carbon is stored in these forests you have to physically walk to randomly assigned sample plots and carry out measurements based on internationally recognised survey methodologies. This can only be done once the area to protect has been identified and the official village land-use plans are in place.

I was part of the team which surveyed the Ntakata Forest, a mosaic of deep forested valleys between steep-sided ridges, the higher slopes of which are covered by short grass and miombo woodland, an important habitat for many animals like chimpanzees, elephants, roan antelope and others.

Although we had discussed strategy and possible routes before starting, on the ground everything changes. Being 5km away in a straight line from a plot meant a 10-12 km walk up and down the sides of a hill. Once on the spot we marked out a survey plot, a 10-metre radius circle, within which all trees, with diameters exceeding 16cm, are measured using a tailors tape measure.

Other information including tree heights, tree species, habitat, gradient of the slope is collected. In the same area other three 10m radius plots are surveyed at a 50m distance from the central plot and at different angles. Once completed, we attempted to reach other sample plots, several kilometres through the bush, but never succeeded more than a plot per day.

Roughing it in the forest

Walking in the forest for many hours and camping in the bush can be tough and surely is not for everyone. It is tiring and in some areas, the sweat bees do not give you a break. Furthermore, you have to consider the unpredictable risk of being in a place where nobody can come if anything happens. The only recommendation I received from my teammate and friend Marc Baker was “don’t hurt yourself”.

Our GPS (Global Positioning System) and satellite images weren’t enough, and we had to trust Mzee Mlay’s knowledge of the forest to find water. He is an old, experienced man, who arrived in Lugonesi village in 1969, and was the only one who could guide us to rivers and streams on which we totally relied for drinking, cooking and washing. Two village game scouts came along as part of their training as they will be responsible for patrolling the area as the project progresses.

This kind of project demands that you work closely with local communities; listening to their needs is as crucial as providing them with modern tools and training because it will affect their approach to forest conservation and consequently the success of the project. The contrast between the simple efficiency of the Tanzanian guys in these remote habitats and myself was so obvious. As they walked in plastic wellington boots, wearing no socks, I was struggling to keep up with the group despite my modern walking shoes with proper skid-proof vibram soles.

No matter what, I always think everyone should live such enriching experiences. I slept in the wild, I learnt and implemented new survey methodologies, I tasted fruits from the forest, ate honey collected in the bush, explored remote areas but most of all I got proof of the value of forest conservation and the impact it has both globally and locally.

With increasing pressure on land and habitat depletion throughout Africa and across the world it is so important to support good land-use planning and helping communities understand that well-planned habitat conservation can improve their livelihoods. It ensures that food production is not threatened and enables economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()