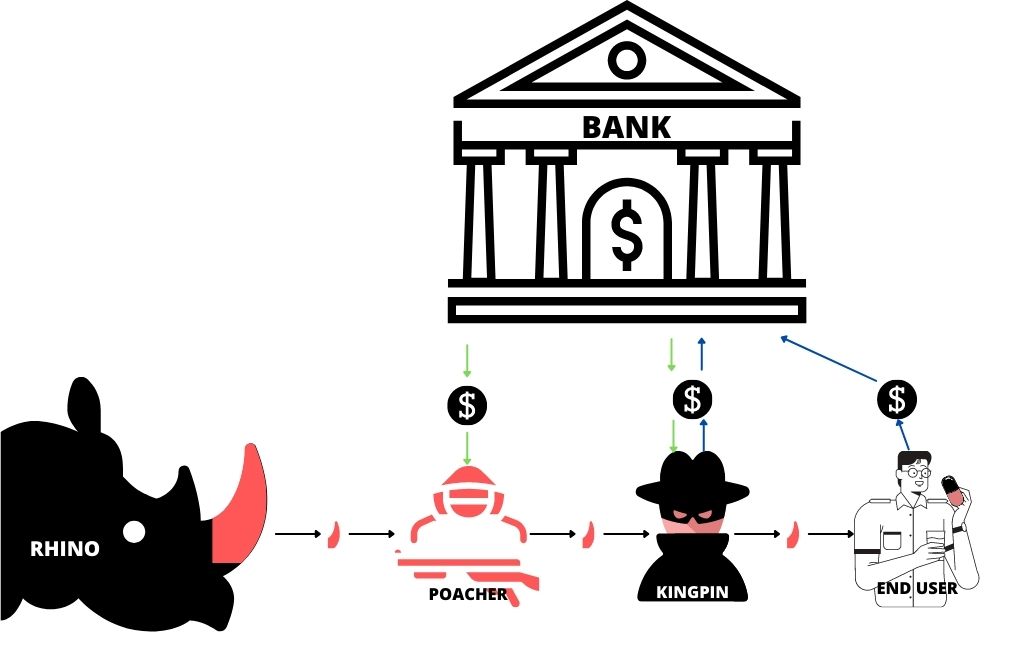

According to the Financial Action Taskforce’s 2020 report, illegal wildlife trade (IWT) generates between seven and 23 billion USD annually for international, organised crime syndicates. Investigations by the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) show that cartels are using formal banking systems to launder the proceeds, largely undetected. The authors of the new EIA briefing call on major financial institutions to play their part in helping authorities identify transactions linked to IWT. The failures of banks to scrutinise the financial footprints left by syndicates have resulted in the loss of vital opportunities to disrupt trade.

According to the report, while IWT is a global concern, the main markets for the bulk of the trade are in east Asia. This is particularly true for elephant, rhino and pangolin parts, which the UN Office on Drugs and Crime recently identified as the three species accounting for some 56% of all illegal wildlife seizures.

Using case studies broken down into different species and routes, the EIA report analyses the financial flow linked to specific forms of illegal wildlife trade and major seizure incidents. In many cases, syndicate members received payment directly from buyers into their personal bank accounts (or those of family members) without any apparent concern for detection.

One case study documents how, in late 2013, some 4.8 tonnes of ivory valued at 5.9 million USD was seized in Tanzania. (Tanzania has lost more elephants to poaching than any other African country in recent decades – its population plummeted by 60% between 2009 and 2014). Upon investigation, it turned out that the smugglers were using a network of front companies ostensibly involved in the trade of agricultural products, food, and marine products. On one particular day, half a million dollars moved through a Tanzanian bank account linked to a front company, but the bank failed to identify or flag the suspicious transaction. The formal banking system was used for transfers in both dollars and Tanzanian shillings, but large cash deposits failed to attract any attention.

According to the EIA, the apprehension and prosecution of wildlife traffickers for money laundering offences are extremely rare, even though this line of investigation can pinpoint high-level people within a syndicate and strengthen criminal cases. Fortunately, there are signs that this is gradually improving, and financial intelligence units are putting more emphasis on wildlife crime cases. This, in turn, should see financial institutions following suit.

The briefing emphasises that it is critical for these financial institutions to recognise the potential risk that wildlife trafficking brings to their organisations. Naturally, the larger, local institutions in emerging markets carry the most significant risk. While global banks have shown limited progress, regional and local banks are not involved to the necessary level. According to the authors, this can largely be explained by a lack of conformity across jurisdictions in terms of the treatment of wildlife trafficking, with disparate classification, laws and policies acting at cross-purposes. Given the lack of legal frameworks to establish potential liability, it is perhaps unsurprising that wildlife crimes are not a risk priority for many financial institutions.

Even once the gaps in the law are filled, the resources directed towards the financial aspects of wildlife crimes are also minimal, left to a small number of law enforcement agencies with powers relating to money laundering and banking and a handful of NGOs. Notably, financial crimes are often viewed through the lens of fighting organised crime and are often very transaction-specific. However, the EIA points out that many of the banking services provided (such as loans or credit facilities) may be having a far greater impact on IWT than once-off transaction dealings.

As such, the report argues, IWT in the financial sphere should be viewed as part of a broader effort to conserve the environment, not just as a pursuit of organised crime. Disrupting wildlife trafficking will require complex strategies at a deep structural level as the current piecemeal approach is not effective. Financial institutions need to coordinate and play their part in the fight against wildlife crime.

As Julian Newman, EIA’s Campaigns Director explains, added: “Private sector banks have a vital role to play in ensuring that wildlife criminals cannot hide their ill-gotten gains in the financial system… They can start by assisting governments to follow the money and reduce the profit incentive behind illegal wildlife trade, helping the authorities to build anti-money laundering cases and to seize assets.”![]()

The full briefing can be accessed here: “Tackling Financial Flows from Illegal Wildlife Trade in East Asia”, Environmental Investigation Agency, March 2021

For further reading, see “Money Laundering and the Illegal Wildlife Trade”, Financial Action Task Force, June 2020

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()