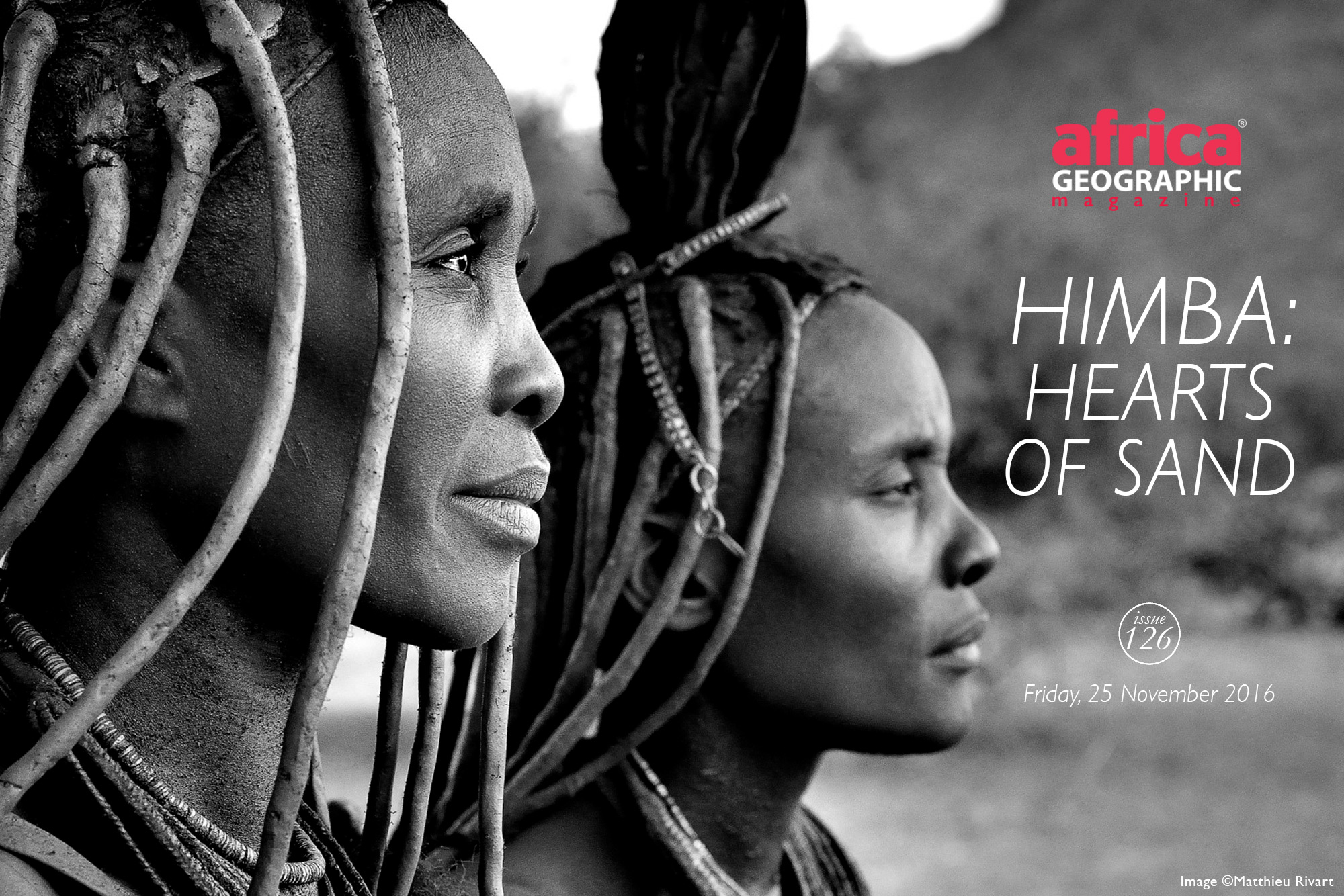

Himba: Hearts of Sand

Travel photographer Matthieu Rivart has spent a great deal of his time travelling to some of the world’s most remote places to document the beauty of vanishing cultures. These trips are his attempt to understand human nature, and to preserve its essence through photography before our world becomes less rich in cultural diversity. The Himba tribe is one of the first indigenous tribes that Matthieu ever heard about.

Living in the northern desert region of Namibia, the Himba are a semi-nomadic people whose population is estimated to be around 50,000. As this region is considered to be one of the wildest on the African continent, they have largely managed to resist modernisation.

Every time Matthieu visits the Himba, he drives through Namibia to reach Opuwo, the small capital of the Kaokoland region, which is close to the border of Angola. In Opuwo he meets a local guide, who shows him the way to the most remote villages, introduces him to the inhabitants, and also plays the role of translator between the photographer and the people.

From his own experience, Matthieu can testify that being accompanied by a good guide is the key to a successful trip. Before heading to the Himba villages, Matthieu and his guide buy food to show their gratitude to the tribe for welcoming and spending time with him. In every encounter he has, Matthieu first builds a strong link with the individual before taking a photo. He believes that a good photograph relies on a unique interaction between two people, so he has always been reluctant to give money in exchange for taking photos, as he believes that paying people prevents creating a genuine connection. He also fears that money earnt from cultural tourism could threaten the Himba’s traditional way of life, as the financial incentive erodes at the culture and turns the people into objects of entertainment who are merely required to re-enact traditions for spectators.

? © Matthieu Rivart

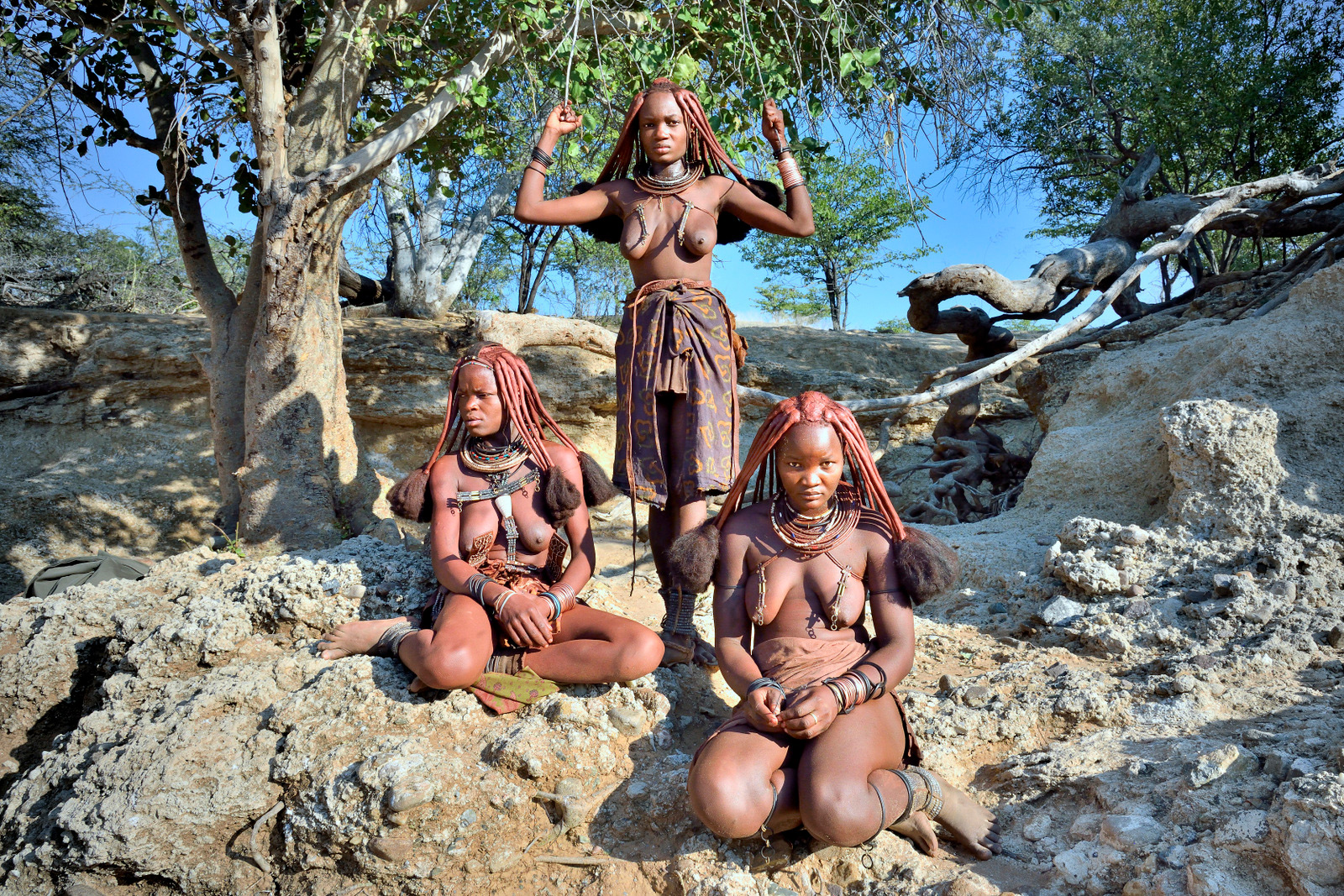

Himbas are particularly known for their beauty regime, as they cover their skin and hair with a red mixture called otjize, which is made of ochre and butterfat.

As Himba live in isolated desert regions, access to water is a daily concern, and the precious resource is reserved solely for drinking. Over time, water has even developed a holy element, and many Himba women actively avoid putting their body in contact with water.

Otjize is used to protect the skin from sun and insects, and to perfume the body. It has both a hygienic and aesthetic function, and rubbing their skin with this mixture is part of a morning ritual for Himba women. It is also used to cover jewellery, clothes and headdresses, and is re-applied to hair braids roughly every two months.

In addition to this, women also burn aromatic herbs and roots to perfume their body. On such occasions, they sit by the burning herbs under a blanket and wait for several minutes until the perfumed smoke has done its job. It’s quite the sight to see when a woman removes the blanket, as a cloud of smoke temporarily hides her!

? © Matthieu Rivart

Jewellery and headwear both play an important role in Himba culture, as they reflect the status of a person. Many Himba women fix hair extensions made of goat hair to their natural hair, which is then applied with otjize. This hairstyle shows that the girl has reached puberty and is now considered a woman, and she will keep that hairstyle throughout her adult life.

Himba women also wear a headdress if they’re married, which usually takes the form of a small hat made of leather. During one of Matthieu’s stays, he met women who were crossing the desert on foot to visit relatives. As they wanted to travel lightly, they just placed a piece of plastic bag between their central braids to make sure their status as married women could still be recognised.

The jewellery of many Himba women consists of a mix of plastic bracelets bought at the closest market, recycled wire, and more traditional necklaces. The most iconic of them, called ohumba, is made of metal beads that support a shell. This necklace, which is a symbol of fertility, is passed down from one generation to the next and isn’t always worn on a day-to-day basis.

During Matthieu’s stay in one Himba village, two young girls were particularly interested in looking at the photos that he was taking, and were complimenting each other on their beauty. They would even use their image on the screen as a way of knowing how to readjust their jewellery – before asking for another photo to be taken!

? © Matthieu Rivart

Young Himba girls have a specific hairstyle that is easily recognisable – this consists of two braided hair plaits that extend forward over the forehead. Boys, on the other hand, have just a single braid that extends backwards to the rear of the head.

Once a girl has her first menstrual cycle, her status changes and a ceremony is organised to celebrate this rite of passage. Before attending the ceremony, the girl must leave the village for several days on her own. When she’s back, the village organises for an animal to be sacrificed, which is usually a goat, and the girl receives jewellery that will show her new status. A change of hairstyle will also be part of the transition, as the girl, who is now a woman, will wear her hair in the traditional braids covered with otjize.

? © Matthieu Rivart

Meeting traditional tribes requires showing respect and developing trust for the experience to be meaningful for both parties. Nowadays, with cultural tourism on the rise, genuine encounters with tribal communities are harder to achieve and often involve travelling to remote areas that tourists don’t tend to visit. It is important to spend time with the people and to adapt to the local way of life to integrate a bit in the community. Matthieu also feels that it is important that visitors interact without disturbing the daily life of the village – even if this means refraining from taking photos at first.

During Matthieu’s first trip to a Himba village, he met the young woman in this photograph. She was living in a small village occupied by a dozen inhabitants. After several days spent in the village, she became more familiar with Matthieu’s presence, and they spent a long time talking about the meaning of her jewellery – their discussion became so natural that taking this photograph happened organically.

? © Matthieu Rivart

For many visitors, the proportion of women in Himba villages is striking. The main reason for this is that men spend most of their time looking after the cattle and sometimes have to be away with the animals for several days to lead them to areas with sufficient amounts of grass for grazing.

The women, on the other hand, stay in the village where their daily life consists of looking after their children, collecting wood to build houses, or preparing meals. Even during their demanding and sometimes physical tasks, which can even involve digging for water in the sand of a dry riverbed, Himba women still wear their jewellery, which is part of their identity.

Men can marry several women, depending on their level of wealth, which is mainly judged by how many cattle they own. But women are only permitted to have one husband. Although this may be the case, Himba society is relatively open-minded with regards to relationships between men and women, and married women tend to have boyfriends, while some single women sometimes even have children with married men.

? © Matthieu Rivart

Himbas often face discrimination due to their ancestral way of life – especially with regards to their partial nudity, as women tend to wear short skirts made of goatskin. As the modern world closes in, the Himba often have to negotiate the gap between their traditional culture and consumer society. In Opuwo, Himba women can sometimes be seen in supermarkets. To afford their purchases, many are forced to sell their cattle or their jewellery, which gradually detaches them from their ancestors and traditions. Nowadays, more and more Himbas are also leaving their villages in pursuit of a more prosperous way of life.

When Matthieu spends time with tribes, he systematically shows people the portraits and photos that he takes. He feels that this helps to establish trust, as people can see exactly what he is doing, especially if they are not used to cameras.

? © Matthieu Rivart

Three places are particularly important in an onganda (Himba village) – the hut of the oldest man of the clan, who is the leader of the village, the kraal (livestock enclosure), and the okuruwo (holy fire).

The okuruwo plays an important role in daily life and, during his last stay with the Himbas, Matthieu would spend evenings gathered around the fire with the community, sharing the traditional porridge made of flour and goat milk, while the elder would tell the children stories and the women would dance and sing.

The Himba believe that the holy fire is a medium by which they can communicate with the spirits of their dead ancestors, and when the fire is not lit, it is considered offensive for foreigners to near or cross the fireplace.

One night, Matthieu recognised a young girl called Makupuaere sitting by a fire when most of the villagers had already retired to their huts to sleep. When he was close enough, he took a photo of her. The sound of the shutter echoed in the silent night, but Makupuaere did not move as she was sound asleep.

? © Matthieu Rivart

Taking photographs in indigenous villages means sharing the daily life of its inhabitants. As they usually live in remote areas, they’re quite reluctant to see foreigners so, to be accepted, one needs to adapt to their way of life, which is part of the magic of the experience.

Social ties are at the heart of daily life in any Himba village, which is made up of relatives. Communities are quite small – the biggest village that Matthieu has stayed in was composed of a dozen huts, while the smallest was a mere group of three huts inhabited by just a dozen of people

Also read: Himba – a people in transition

About the photographer

Raised in France, but now living in South Africa, Matthieu Rivart has been passionate about photography for a decade, and he strives to achieve the balance in his endeavours between expressing creativity and preserving authenticity.

Raised in France, but now living in South Africa, Matthieu Rivart has been passionate about photography for a decade, and he strives to achieve the balance in his endeavours between expressing creativity and preserving authenticity.

Inspired by the work of anthropologists and explorers, Matthieu Rivart travels across the world – through deserts, jungles and mountains – to witness the beauty of diversity in humans and nature. As the winner of several international photo contests and prizes, Matthieu’s work can be enjoyed online on his website and in art galleries. You can also follow him on Facebook and Instagram.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()