Guarding the golden goose

The Great Wildebeest Migration is one of the most extraordinary wildlife events on Earth: over a million wildebeest, accompanied by zebra and gazelle, moving in a continuous cycle between the Serengeti and the Maasai Mara. It is a story of survival and renewal, of predators shadowing prey, of grasslands being grazed and replenished. It is about the balance of an ecosystem that has shaped life in East Africa for centuries.

And yet, in the way we market and consume it today, the migration is often reduced to a single spectacle: wildebeest river crossings. If we are not careful, we risk treating this natural marvel as a one-off attraction rather than a fragile, living system – and in doing so, we could kill the golden goose that has nourished both wildlife and communities for years.

How the media changed the story

For decades, visitors celebrated the scale of the migration itself: the sound of hooves rolling across the plains, the dust clouds on the horizon, the predators waiting patiently at the edges. The wonder lay in the abundance – in witnessing one of the last great movements of animals on Earth.

But mobile phones, cameras, and marketing campaigns changed the story. River crossings, with their plunging wildebeest and ambushing crocodiles, are cinematic. They became the easy sell for glossy brochures and television documentaries, and today for social media. Tour operators began building itineraries around them, knowing that images of wildebeest hurling themselves off cliffs were enough to persuade travellers to part with their money.

The danger is that we have narrowed the migration into a single moment. Guests come to Serengeti National Park and Maasai Mara National Reserve seeking one dramatic scene, and investors build lodges to service that demand. Too often, crossings are treated as entertainment rather than as what they truly are: moments of life and death.

The economics of the Great Migration

The Migration is not just an ecological marvel – it is also an economy in itself. Tens of thousands of people depend on it for their livelihoods: from guides and drivers to camp staff, lodge owners, and communities offering spare rooms. Many people have invested their savings in safari vehicles or in building modest camps to capture some of the tourism demand. I believe we often underestimate the knock-on effect of how many families are completely dependent on tourism – especially in East Africa.

This reality makes the problem complex. On one hand, we cannot simply strip away those opportunities or pull the rug from beneath people who have invested their lives in tourism. On the other hand, the uncontrolled growth of camps and vehicles is placing enormous pressure on the phenomenon that sustains them.

There is also an uncomfortable contrast between operators. Some camps genuinely invest in conservation and community: they employ and train local people, channel funds into protection programmes, and even secure land for wildlife. Others, however, operate as little more than roadside hotels, offering beds but contributing little to the wider ecosystem. Fancy lodges with polished marketing campaigns and high-end interiors can sometimes fall into this category too – their glamour and branding may impress guests, but in reality, they are no more supportive of conservation than the simpler roadside options.

Even good management can be undermined. The Mara Triangle, for instance, has invested heavily in upgrading its infrastructure and maintaining roads. But this has drawn more and more vehicles from outside its borders, all coming to benefit from these improvements. By raising standards, the Triangle has inadvertently attracted an unsustainable burden of extra traffic.

This is the heart of the challenge: the migration has become such a vast economy that everyone wants a piece of it. That is understandable. But it is also shortsighted. If we continue to exploit it without restraint, we risk destroying the golden goose itself.

In preparing this piece, I reached out to eight local Maasai guides to hear their perspectives. All chose to speak anonymously, a decision that is telling – there is a fear of repercussions for voicing criticism. Yet each of them echoed the same sentiment: the current scale of overtourism is eroding the heart of the migration. They spoke of how the experience has been degraded, not only for wildlife but also for visitors, and how the once-proud reputation of ecotourism in the Mara is being chipped away. Their words were sobering and a reminder that those closest to the ground often see most clearly the direction in which things are heading.

Enforcement and accountability

One of the most urgent problems is the weakness of enforcement. Fines, too often, are toothless. I have witnessed guests offer to pay fines on behalf of guides – essentially encouraging them to break the rules.

The conversation goes like this:

“How much is it to drive off-road here?”

“We are not allowed.”

“Yes, but if you did, how much would they fine you?”

“10,000 Kenyan Shillings.”

Okay, great. Drive off-road, and we will pay for it if they stop us.”

I have heard this exchange on many occasions. It exposes a failure in the system. If fines are so low that they become part of the cost of doing business, they will never serve as a deterrent. What is an extra US$80 or so on top of a trip that would have cost thousands? Heavy penalties – financial AND professional – must be introduced. Guides must realise that breaking the rules is not an option.

The false Great Migration fixes

In conversations about overtourism in the Mara, a few simple “solutions” are often put forward. Raise park fees. Cap visitor numbers. Ban new developments. On the surface, these sound appealing. In practice, they are not straightforward.

Take the issue of raising park fees. Two years ago, the cost to enter the reserve rose sharply, from US$80 to US$200. We were told this would reduce numbers. It has not. Cars still crowd the crossings; the only change is that visitors now pay more, and the public knows management is collecting greater revenues.

Imagine if fees rose again, to, say, US$500 per person per day. (Keep in mind it currently costs US$1,500 for a permit to view gorillas in Rwanda for a single hour!) Lower-end lodges and camps would potentially collapse overnight. A whole tier of travellers would be priced out. Worse, conservation would risk becoming elitist. Local communities, whose support is vital to the survival of wildlife, could be locked out of landscapes they have protected for decades.

Even the current structure is flawed. Fees are charged per person, but the pressure at crossings comes from vehicles. A car carrying one guest takes up just as much space as a car carrying nine. The system should always have been based on vehicles, not individuals.

And what of development caps? In principle, they are desperately needed. But consider the families who have already invested in cars and modest accommodation. They cannot simply be shut down. Yet, if new camps keep sprouting unchecked, the cumulative pressure will push the Mara past the point of no return.

None of these fixes is as clean as they first appear. The problem is more complicated, and pretending otherwise risks worsening the situation.

Towards real solutions

Solution 1: Capped vehicle entry

A broad cap on vehicle numbers entering the Mara could help, but the reserve is vast. The real strain lies at bottlenecks, not across the entire landscape. A more nuanced approach is needed. The challenge is how such a carrying capacity would be determined in the first place – and whether it could be enforced fairly. The Mara’s boundaries are porous; there are no fences, and it is a poorly kept secret that vehicles have not always entered or exited through official gates. If a capped system were ever to work, it would require rigorous planning, robust monitoring, and genuine commitment to control access. There is also the real question: if the park fee was raised to US$500, US$1,000 or even higher, where would that massive increase in revenue end up?

Solution 2: Viewing platforms and hides

Another idea that surfaces regularly is to construct fixed viewing points, hides, or even grandstand-style platforms, much like those at a golf tournament. The suggestion is that vehicles would park at a distance, and visitors would then walk – perhaps even through tunnels – to these structures, where they could watch the crossings in relative order and safety.

On paper, it has some appeal. But in practice, it is fraught with problems. There are at least 20 recognised crossing points along the river, many with multiple entry and exit spots. To cover them all would require a significant number of platforms. If a crossing happened just out of sight of one, visitors would miss it entirely. The Mara River is unpredictable, its water levels rising and falling throughout the season. Any hide would need to be constructed at considerable height to avoid flooding, which would demand steel, concrete, and large-scale infrastructure.

Even if designed to be discreet and aesthetically sympathetic to the landscape, such structures would still need to accommodate hundreds of people at a time. The resulting human footprint – both visual and physical – would be immense. While the concept is often put forward with good intentions, I do not believe it is a workable or desirable solution for the Mara.

Solution 3: Premium crossing permits

Another proposal is to introduce a premium ticket for access to river crossings. While this might reduce congestion, it risks creating more problems than it solves. Large operators would almost certainly buy up tickets well in advance, dominating the system. A black market could emerge, with permits being sold at extortionate prices on the eve of guest arrivals. In such a scenario, little of the money would reach conservation; middlemen would pocket most.

Solution 4: Controlled crossing points

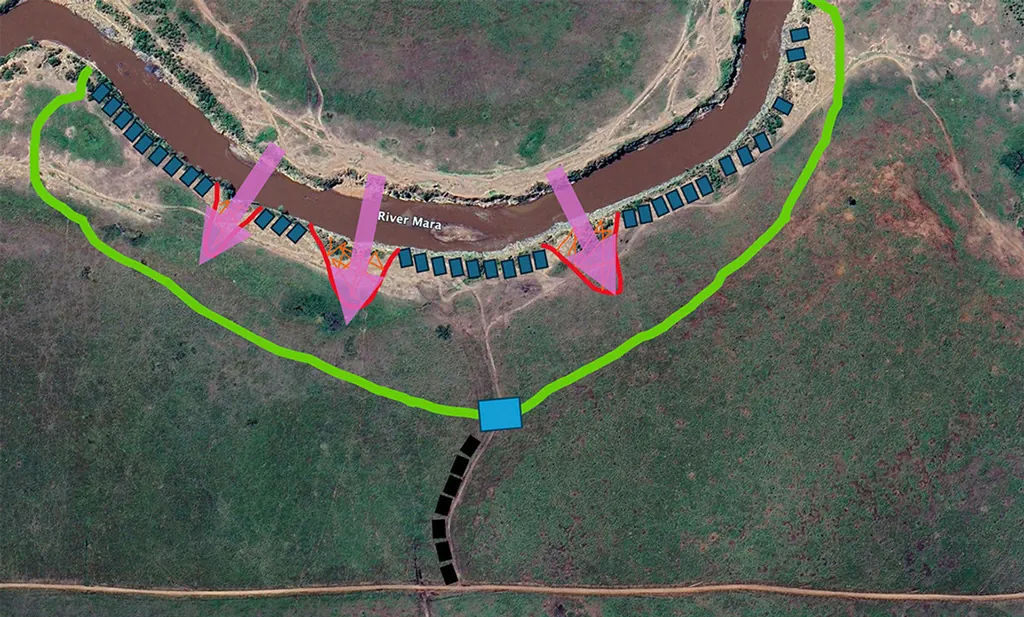

The most promising approach may be to regulate crossings directly – not by charging extra, but through careful management and oversight. Access could be granted on a first-come, first-served basis, with vehicles guided into predetermined viewing zones. Each crossing point could be mapped and assessed to determine how many cars it can sustainably handle, ensuring that every vehicle present has a fair and unobstructed view.

This simple change would remove the incentive for dangerous behaviour. At present, much of the chaos arises from the limited number of good vantage spots. Vehicles race to secure them, turning crossings into something resembling the start of a rally. By designating parking areas and controlling numbers, that tension would disappear.

Some gentle landscaping might be required – trimming long grasses, levelling sandy banks, or clearing bushes – but this is a minor and reversible impact compared to the benefit of restoring calm and order. Natural barriers such as logs, rocks, or trenches could also protect the wildebeest entry and exit points.

This is not just an idea. I submitted such a proposal to the Mara Conservancy, which in turn forwarded it to Narok County. The concept remains simple: restore order at crossings, cost visitors nothing, and demonstrate that patience and ethics can be rewarded.

These four solutions are by no means the only options. They are simply those I hear most often discussed, and the ones I have personally considered in detail. There are undoubtedly other creative and practical approaches worth exploring.

Alongside longer-term structural solutions, there are also immediate steps that could make a significant difference. First, only accredited and registered professional guides should be allowed to conduct safaris in the Mara, ensuring a higher standard of behaviour and accountability. Second, a portion of the increased park fees should be directed towards employing and equipping far more rangers – with vehicles, cameras, and the authority to hand out substantial fines. During migration season, especially, a visible and empowered ranger presence is essential. Finally, every visitor to the Mara should be asked to sign a simple but powerful code of conduct, one that makes clear that respect for wildlife is paramount. A model exists in the Palau Pledge, where visitors to the Pacific Island nation sign a promise in their passports to act responsibly and preserve nature for future generations. Such a pledge in the Mara would help shift expectations from the moment a safari begins. In Palau, you cannot enter without signing this pledge to protect the natural environment. Shouldn’t the Mara ask the same of its visitors?

Integrating local access

Another potential step is to guarantee a capped number of places for Kenyan residents each day, at a reduced rate. This would ensure that local people remain connected to their own wildlife, while international visitors continue to provide the bulk of funding. Done properly, this could be a win-win: inclusivity without undermining financial sustainability.

A cultural reset, transparency and trust

Finally, there must be a shift in how we view wildlife. Safari is not a right, but a privilege. Crossings are not “content” to be consumed and shared; they are moments of life and death. Guests should also be encouraged to spend time with the herds away from the river, immersed in the sheer magnitude of life unfolding across the plains.

A lack of trust underpins all of this. Where does the money go? Park fees generate millions of dollars, but how much reaches conservation on the ground? How much reaches local communities? And – though this must be asked gently – how much ends up with individuals?

These questions are not accusations, but they must be addressed. Transparency would transform perceptions. If visitors knew how their fees were spent, they would be far more willing to pay, more patient with restrictions, and more supportive of conservation strategies. The same is true of lodge approvals: who decides, and why? Openness would build confidence; secrecy only fuels suspicion.

The role of guests

Guests play a crucial role. By choosing camps that actively support conservation and employ local people, they can help ensure that tourism strengthens the ecosystem rather than simply extracts from it. Camps that invest in land, training of people, and protection of wildlife deserve to be supported over those that do the bare minimum.

Guests should also set expectations with their guides early in their trip. Make it clear that tips will be based on knowledge, interpretation, and respect for nature – not on reckless driving, racing between sightings, or forcing proximity at crossings. Guides should be rewarded for their patience, knowledge, storytelling, and ethics, not for taking risks.

Choose safari operators who prioritise conservation and responsible practices when experiencing the Great Migration. Africa Geographic’s Great Migration safaris offer you this extraordinary spectacle while protecting the ecosystem that sustains it. Or, ask us to build the perfect safari, tailored just for you.

Choose safari operators who prioritise conservation and responsible practices when experiencing the Great Migration. Africa Geographic’s Great Migration safaris offer you this extraordinary spectacle while protecting the ecosystem that sustains it. Or, ask us to build the perfect safari, tailored just for you.

And here’s a radical thought – what if lodges simply paid their guides higher salaries and scrapped tipping altogether? Imagine an industry where the incentive to impress came from stable, sufficient pay and professional pride, not from the chase for the biggest end-of-trip envelope. Of course, tipping is far too deeply embedded in safari culture for this to ever happen, but it’s worth noting that the pursuit of tips is one of the root causes of the bad behaviours we see on the ground today.

Every choice a guest makes matters. The type of camp, the questions asked, the behaviour expected – all contribute to shaping the future of the Mara.

A call to act

The Great Wildebeest Migration is under pressure. In recent years, the herds have spent less and less time in the Mara – a fact that individually everyone knows, but collectively no one appears to acknowledge or talk about. Climate change plays a role, but so too do human factors: fences, frequent burning, vehicle congestion, and the sheer density of camps along migratory routes.

We cannot kill the golden goose. We must nurture it. We must accept that change is needed, even if it is uncomfortable.

The question is not whether action should be taken. It is those who will be bold enough to make the decisions. Years ago, management admitted that the Mara was at a breaking point. Since then, numbers have grown, crossings have become more chaotic, and more large camps have been built; the only meaningful change has been a US$120 hike in park fees. That is not enough.

Above it all, the solution must come from within. Outsiders like myself can advise, support, and share ideas, but for real traction, change must be led by the Maasai community – the custodians of this landscape. Their voices, leadership, and authority are essential if the Mara is to find a sustainable future.

Who will be bold enough to make the difficult decisions? What will it take before action is truly taken?

The Great Migration is a global treasure, and protecting it requires courage and honesty. It will mean facing uncomfortable truths, regulating where regulation is overdue, and choosing long-term sustainability over short-term gain. If we fail, the cost will be irreversible – for wildlife, and for the people who depend on it.

This article was originally published on Adam’s blog, AdamBannisterWildlife.com

About Adam Bannister

About Adam Bannister

Adam Bannister is a South African-trained biologist, safari guide, author and storyteller who has spent nearly two decades immersed in some of the world’s most iconic wild places, from the Sabi Sands and Maasai Mara to the deserts of Rajasthan and the forests of Rwanda and Peru. With a passion for training guides, Adam works across Africa and India to help guiding teams unlock their full potential, combining science, storytelling and presence to elevate the guest experience. His strength lies in translating complex natural phenomena into meaningful, memorable moments in the field. Read more about Adam here.

Further reading

- Sustainable safaris: Can tourism truly protect nature? Tourism funds conservation, yet unmanaged growth risks overtourism. Christy Bragg looks into the question of mindful safaris that can sustain Africa’s wildlife and people

- Are viral safari guides putting content before conservation? Adam Bannister makes calls for a restoration of ethics, respect, and integrity in wildlife guiding

- The vast Serengeti in northern Tanzania is home to an extraordinary amount of wildlife and plays host to the greatest show on Earth – the Great Migration. Read more about Serengeti National Park here

- Longing to know more about the Maasai Mara? This how to guide on Kenya’s Maasai Mara will have you contacting Africa Geographic to book your next African safari

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()