ARID EDEN

As dusk descends over the red sands of the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, her animal choir prepares for another encore-worthy performance. First, the barking geckos emerge to set up the staccato rhythmic accompaniment for what is to come. The pennywhistle arpeggios of the pearl-spotted owlet – disproportionately loud for such a small bird – weave through the gracenote “brrps” of the scops owls and trills of the rufous-cheeked nightjars. Waiting patiently in the wings, a lion adds a booming baritone that echoes over the ancient, ephemeral, rivers, setting the stage for the main performance of the evening.

As the sun dips below the horizon, the scenery is bathed in the colours of the Kalahari, and a solitary jackal howls. One by one, its neighbours add their voices to the call and response melody, a haunting, lupine soprano that cuts through the night and raises goosebumps on human skin.

This is the song of the Kgalagadi

The Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park

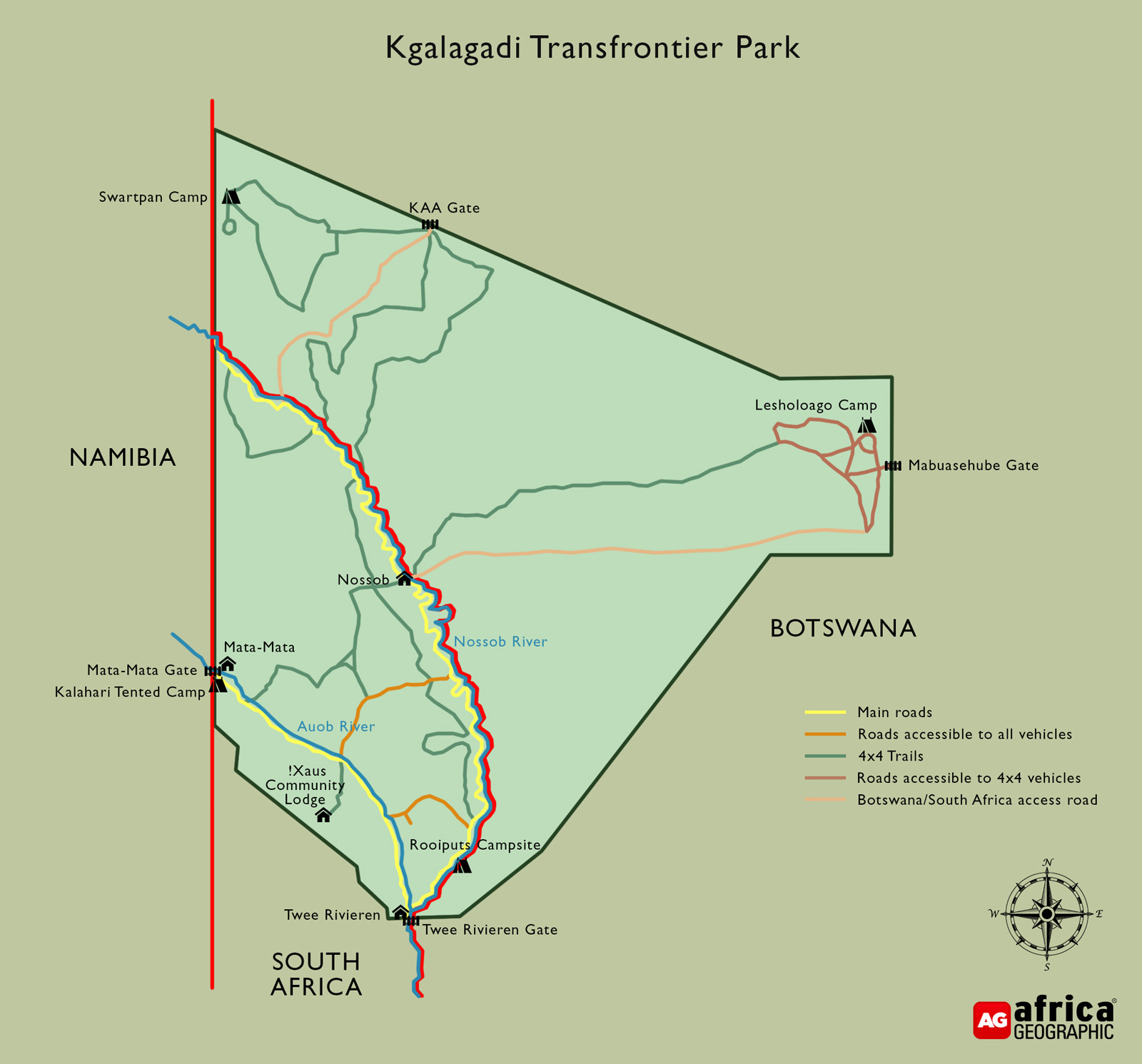

The Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park covers an enormous 35,551km2 (3.5 million hectares) in the Kalahari Basin, incorporating national parks in South Africa and Botswana. In Botswana’s southwestern corner, the Gemsbok National Park covers nearly three-quarters of the Kgalagadi (28,400km2) while the Kalahari Gemsbok National Park and the !Ae!Hai Kalahari Heritage Park together comprise the South African section in the Northern Cape.

As the oldest transboundary protected area in Africa, the Kgalagadi enjoyed a de facto existence from as early as 1948, when informal agreements between the national parks ensured that the entire ecosystem was holistically managed. However, it was only in 1999 that South Africa and Botswana legally formalised these agreements, and the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park was officially opened in May 2000. Visitors are free to travel between the two countries within the park without a passport, provided they exit from their original country of entrance.

While the rolling red dunes and Kalahari sandveld plains are spectacularly beautiful, life in the Kgalagadi centres around its two ephemeral rivers: the Nossob and the Auob. The rivers hardly ever flow at surface level; instead, underground water supplies the surrounding camelthorn trees and other vegetation which, in turn, provide essential nutrients to the park’s herbivores at the end of the long dry season.

The basics

The Kgalagadi – which possibly translates as ‘the land of thirst’ – is not an appropriate destination for spontaneous exploration or the inadequately prepared visitor. Main camps aside, most of the wilderness camps and campsites offer only basic facilities and little in the way of phone signal. Though there are entrance gates on both the South African and Botswanan sides, most of the park infrastructure and camps are dotted throughout the South African portion of the park. In contrast, the Botswana side is vast and wild. Large distances and limited roads separate campsites with few facilities and no fuel. This section is only accessible with 4X4 vehicles.

Three main or “traditional” camps in the Kgalagadi are equipped with shops and fuel, as well as electricity (though only Twee Rivieren offers 24-hour power). Twee Rivieren, Nossob and Mata Mata are connected by the park’s main roads which are corrugated but accessible to 2X4 vehicles unless there has been unusually high rainfall. These main camps are the hub of park activity, and visitors can book guided drives (including night drives), guided 4X4 trails and walks.

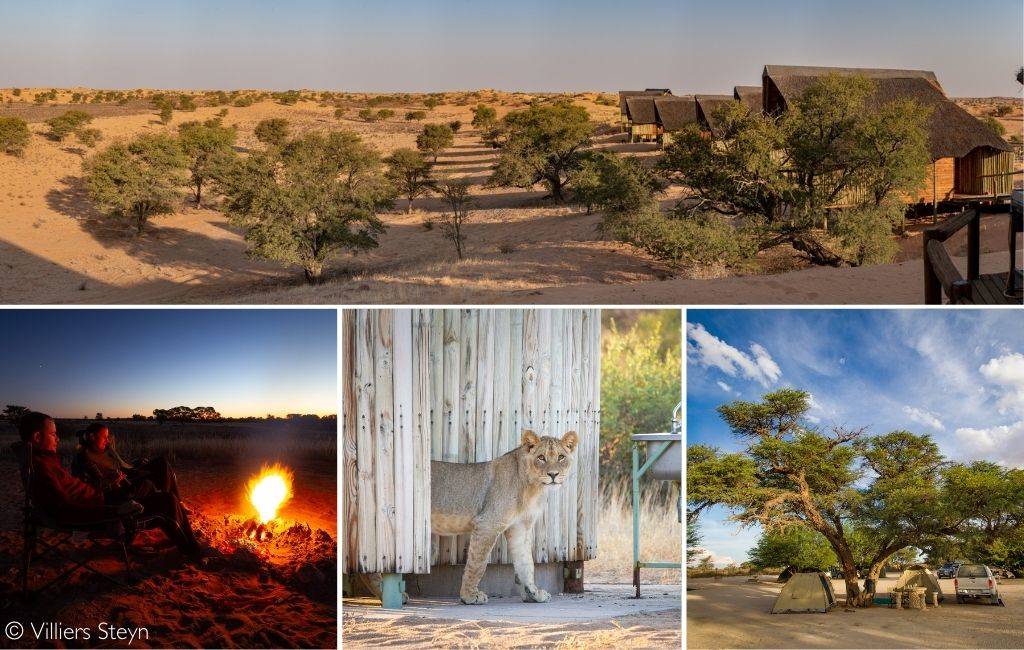

The wilderness camps (powered by solar and gas) and isolated campsites are unfenced, offering an entirely immersive experience free from the trappings and distractions of modern life – including, in some luxurious cases, flushing toilets. As a result, the Kgalagadi is one of the few remaining wild spaces where visitors can lose themselves in nature and revel in the wildlife’s authenticity; especially the ubiquitous, bright-eyed ground squirrels that have learned to capitalise on the generosity (or messiness) of passing campers.

The wildlife

Arid it may be, but the Kalahari ecosystem is a complex web of life well-adapted to extremes. The Kgalagadi itself is probably not suited to first-time safari-goers, particularly not those intent on ticking off the Big 5, because elephant, rhino and buffalo are not present in the park. Nevertheless, the wildlife viewing in the Kgalagadi is exceptional for two main reasons: the profusion of predators and the opportunity to appreciate the underappreciated.

A predator profusion

Of the 60 or so recorded mammal species in the park, nearly a third of these are predators. For most people, top of the list are the lions of the famed Kalahari black-maned pedigree. The Kgalagadi is considered a vital Lion Conservation Unit (as designated by the IUCN Cat Specialist Group) and it is not uncommon to fall asleep to their roars only to wake up in the morning and discover their tracks crisscrossing the previous night’s braai site. Cheetahs and leopards complete the big cat trifecta, especially during the dry season when the desolate landscape makes it somewhat easier to pick them out at a distance. Russet-coloured caracals with their characteristic black ear tufts are relatively common and the Kgalagadi is home to one of the largest (and genetically purest) wildcat populations in Africa.

Of the other large predators, brown hyenas are particularly well-adapted to desert habitats. These shaggy predators patrol the dunes and scrublands in a constant search for their next carcass or moisture-rich tsamma melon. Their spotted cousins are less numerous but more vocal and conspicuous, often wallowing in pans during the heat of the day.

The smaller canid species are some of the Kgalagadi’s most captivating residents. When not serenading each other, black-backed jackals use their canine wiles to eke out a tenuous existence in the inhospitable landscape. Whether they are scrapping over a leftover piece of leathery skin, bravely snatching a morsel of meat from beneath a lion’s nose or launching acrobatic attacks to catch unsuspecting sandgrouse, time spent with jackals is never wasted.

Like the jackals, Cape foxes (also known as silver-backed foxes) can be equally entertaining, particularly for those fortunate to spend time at den sites with young kits, which must surely rank among the world’s cutest baby animals. Unlike the insectivorous bat-eared foxes (which are also present), the Cape fox is the only true fox species in sub-Saharan Africa.

The underappreciated

The Kgalagadi experience is one of quality over quantity, and rushing from sighting to sighting is not a recipe for success. Instead, time, patience and attention to detail yield greater rewards to the discerning visitor, especially if it means a few hours spent at one of the waterholes at dusk and dawn.

Even within the confines of the camps themselves, life abounds. The aforementioned ground squirrels are so commonplace that they are often overlooked. Close observation of familiar individuals, however, reveals that they lead complex and intriguing lives. Their habit of using their tails as built-in parasols and charismatic personalities make them extraordinarily endearing. Yet, they are also consummate survivors, and their reflexes are lightning-fast, as this brave mother demonstrated in her battle with a Cape cobra.

From honey badgers, meerkats, and mongooses to elephant shrews, whistling rats and chameleons, appreciating nature in all her glory is the very essence of exploring the Kgalagadi.

Jumping for joy…

At the risk of repetition, the best wildlife viewing is at the end of the dry season. The animals are forced to congregate around available water resources (particularly the pumped pans), and vegetation is sparse. However, the park is magnificent regardless of the time of year and the transformation effected by the seasons and the arrival of the rain around December is remarkable. Seemingly overnight, the barren, desiccated landscape is revitalised and carpeted in new life’s green flush. As the thunderstorms roll overhead, annual flowers spring up out of nowhere, painting the scenery in flamboyant colours that seem decidedly out of place in a desert.

Herds of blue wildebeest, gemsbok, red hartebeest, and eland congregate in celebration of the rains, migrating within the park to secure the best resources for the birthing season. There is a palpable sense of relief among the animals that survive the savage dry season, and this is particularly apparent in the herds of springbok that seem to jump for joy. Their unique, pronking leaps provide hours of entertainment. While there are solid biological explanations for this behaviour (displaying physical fitness to predators and potential mates), to many of us, these antelopes simply seem to be enjoying themselves.

The experience

The only luxury lodge in the Kgalagadi is !Xaus Lodge which is found on the border of the southern section of the park, in the !Ae!Hai Heritage Park. This 580km2 section of land was set aside for both the ‡Khomani San and Mier communities, and profits from the lodge are fed back to these communities.

The Kgalagadi is a land of extremes, and visitors should be prepared to face them. At the height of summer, the temperatures soar above 40˚C every day, and the relentless sun beats down on the red sands, lifting temperatures to around 70˚C on the surface. As already mentioned, most of the camps are rudimentary, and few are equipped with fans, let alone air conditioning. By contrast, the temperatures at night in winter can drop to well below freezing and where there is plumbing, it is not unusual to wake to pipes frozen solid. Comprehensive planning and research will ensure that visitors get the most out of the Kgalagadi experience.

A stroll around the campsite at night with a UV light will reveal the scorpions emerging to take advantage of the cooler temperatures. This, combined with regular snake sightings, should be sufficient to convince even the most experienced camper to wear sensible footwear at night and carry a powerful flashlight.

Want to go on a safari to Kgalagadi? To find lodges, search for our ready-made packages or get in touch with our travel team to arrange your safari, scroll down to after this story.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()

HOW TO GET THE MOST OUT OF AFRICA GEOGRAPHIC:

- Travel with us. Travel in Africa is about knowing when and where to go, and with whom. A few weeks too early / late and a few kilometres off course and you could miss the greatest show on Earth. And wouldn’t that be a pity? Browse our ready-made packages or answer a few questions to start planning your dream safari.

- Subscribe to our FREE newsletter / download our FREE app to enjoy the following benefits.

- Plan your safaris in remote parks protected by African Parks via our sister company https://ukuri.travel/ - safari camps for responsible travellers